“Lies and blatant fabrications” – this was how the British government described Russia’s clumsy attempt to conceal its hand in the nerve agent attack in Salisbury, by staging a bizarre interview with the suspects. But it might as well be a by-line for the overall pro-Kremlin disinformation campaign that we followed in 2018.

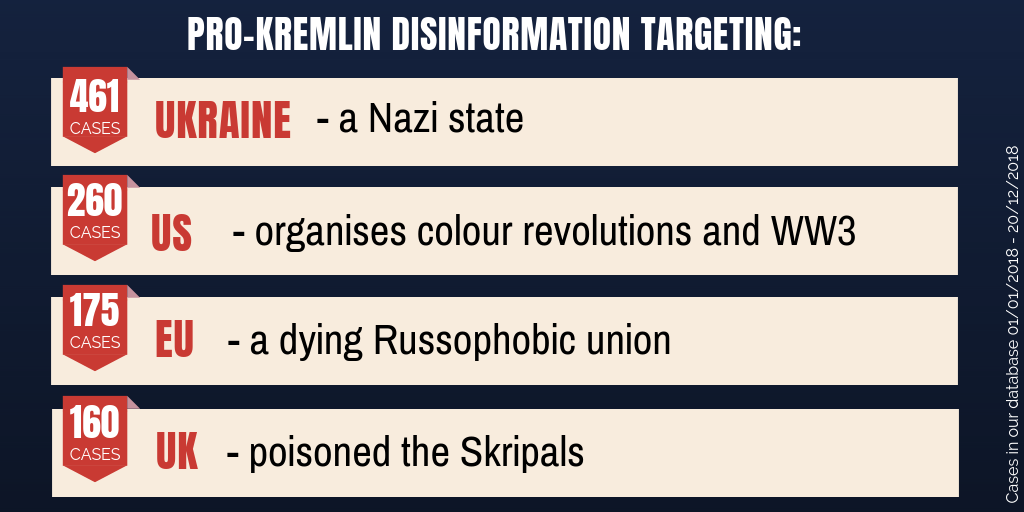

Out of over 1000 cases that we have collected this year, Ukraine emerges again as a primary (and constant) target. However, this year we also witnessed pro-Kremlin disinformation megaphones directed heavily at the EU and in particular the UK, its government and security services over the Salisbury case.

Assault on truth

In the few months following the attempted murder of a former Russian spy Sergei Skripal on British soil, the pro-Kremlin disinformation machine went into over-drive, fabricating one story after another. We saw attempts to convince us that the poisoning, which involved military-grade nerve agent, was a case of fentanyl overdose, alcoholism or other addictions; that it was orchestrated by Ukraine, one of the EU member states, Yulia Skripal’s future mother in law or Theresa May herself. We heard that it was a British attempt to drive public attention away from troubles at home, a justification to hit Russia with another set of sanctions or to boycott the World Cup, and – of course- yet another proof of Russophobia.

By mid-April, we had counted 31 different narratives on the Skripal case coming from the pro-Kremlin sources (the number is now over 40). This is consistent with classic pro-Kremlin disinformation techniques: pollute the information space with as many contradictions as possible, so that the average media consumer loses track of facts. At the same time, this multi-narrative technique feeds a loyal audience of disinformers ready to defend Russia with numerous lines to take. And most insidiously, the abundance of contradictory narratives creates an illusion that objective, fact-based based truth is not possible and so does not exist.

Such multi-narrative disinformation was previously used after the downing of flight MH-17 and the bombing of a humanitarian convoy in Syria, after Russian complicity was exposed. However, from the disinformation point of view, the Salisbury case stands out, as over the course of the year we saw it starting to merge with another disinformation campaign, surrounding the chemical attack in Douma, Syria.

Support and amplify

Soon after the chlorine attack in the rebel-held town of Douma, Syria, Russian-controlled state TV aired video footage of seemingly unconscious children, surrounded by a professional film crew and cameras. As quickly demonstrated, this was falsely presented as evidence of a “fake chemical attack”, supposedly staged by the White Helmets organization. Whereas pro-Kremlin disinformation had blamed the White Helmets for staging the chemical attacks in the past, this time the UK was being accused of instructing them to do so.

Disinformation channels claimed that Syria’s chemical weapons were created by the Brits and that there were no chemical weapons in Syria; that the Salisbury attack and the bombing of Syria were part of a big Anglo-Saxon provocation; and that White Helmets faked the Douma attack to deflect attention from the Salisbury attack. Pro-Kremlin outlets also used disinformation messages surrounding the investigation of the Salisbury attack to discredit the work of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) inspectors prior to their arrival to Douma.

For a timeline illustration of Salisbury and Douma disinformation campaigns click here.

Both disinformation campaigns were played out not only to confuse, to distract and shift blame from the genuine perpetrators, but also amplify and give credibility to one another.

In this context, chemical attacks and chemical weapons were among the most popular disinformation topics of this year. Pro-Kremlin disinformation outlets heavily circulated chemical and biological weapons conspiracies as well as warnings about imminent chemical provocations. Collectively such narratives become instruments to create a distorted reality, where chemical and biological warfare is normalised as a recurring practice of states, and where chemical and biological weapons are used and condoned by anyone except Russia and its allies.

Disinformation premonition

The end of this year was marked by a serious escalation in the Azov Sea, when Russia seized three Ukrainian vessels and their crews after opening fire at them on November 25. However the disinformation campaign on the Sea of Azov started more than a year ago, gradually becoming more intensive and laying the ground for what was to come. Pro-Kremlin outlets reported on cholera near the port of Mariupol, suggesting that Ukrainian authorities hoped for it to spread further. The traditional ‘blame the West’ narrative was there too, as was the myth of the Azov Sea belonging to Russia.

The case of the Azov Sea revealed the long-game of disinformation campaigns, where the aim is not only to distract and distort the facts, but also to prepare the information space well in advance for events that might take place on the ground.

Silver lining?

But 2018 was also the year when significant parts of the pro-Kremlin disinformation machine were exposed to broad daylight. A number of criminal indictments by the US authorities publically revealed the scale, financing schemes, personas and organisations behind the pro-Kremlin disinformation campaigns, as well as their modus operandi.

Social media platforms also began to step up their actions against disinformation. In June and July Twitter suspended over 70 million suspicious accounts and continued the pace in the following months. Besides shutting down suspicious pages and accounts on the platform, Facebook established a “war room”, staffing data scientists and security experts, to protect elections from disinformation attempts. These are encouraging moves, even if much more remains to be done.

Epilogue for the year

This year, we learned a lot about the mechanisms and narratives of pro-Kremlin disinformation. We are more aware and we have more reliable sources of information. Does it mean we can begin to feel safe about being targeted in the (dis)information space? Certainly not. Some of this year’s examples remind us that disinformation is a centuries long tradition that is now tailored to the digital age. Awareness is always a key asset. Next year, don’t forget to question even more.