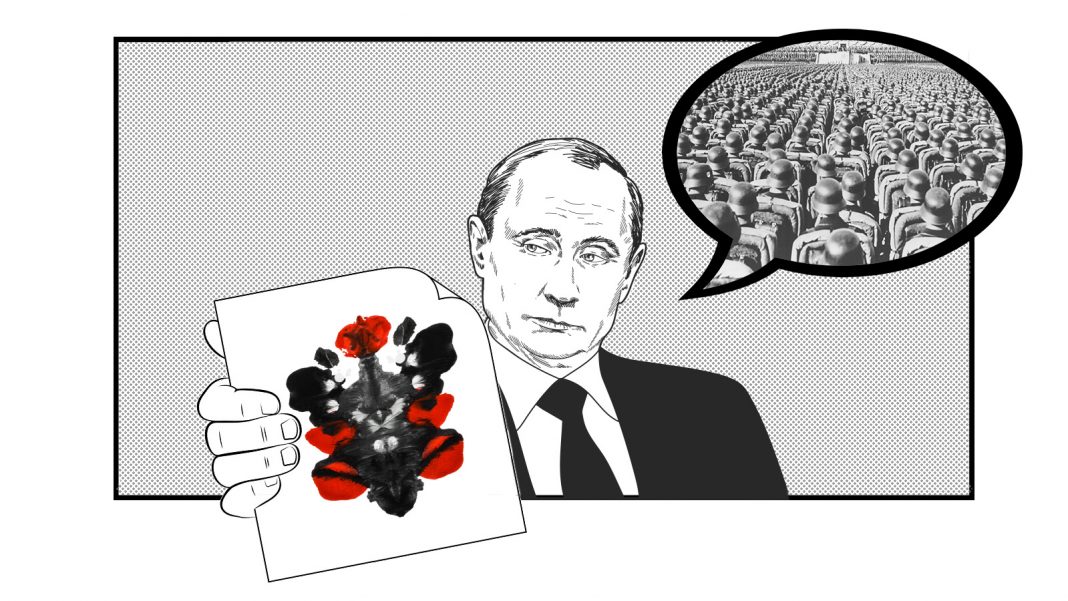

It is a schoolyard defence most of us know. If someone calls you a name you reply, “It takes one to know one” or “you are worse than me”. That is, accuse them of the very charge they made against you. This rhetorical tactic is a projection – a way to shift blame for their own destructive actions.

In his speech aired 24 February announcing the invasion of Ukraine (aka “special operation”), Putin dished out several whoppers of lies. He claimed that the “limited military operation” aimed to ensure the “defence of Donbas” and the “self-defence of Russia”, although Ukraine has never threatened anyone, let alone Russia. He claimed that the “operation” would involve “no occupation”, although Russian soldiers in Ukraine are now establishing just such an occupation in parts of the east and south. Putin outlined “holding elections for a new government”; any fair elections, however, would likely return an overwhelming majority deeply hostile to Russia, if only because Putin’s invasion overthrew a government that was democratically elected in 2019 with over 73 per cent of the vote.

On 16 March, Putin gave a long speech, throwing verbal attacks and wild allegations: the “Neo-Nazis” in Kyiv preparing chemical attack, biological weapons, anthrax, even soon to have nuclear weapons ready against Donbas and Russia. Needless to say, none of the allegations were backed up by a shade of evidence, as it is usually the case for the most insolent disinformation tropes.

Going Nazi…

One claim stood out both on 24th February and on 16 March, however. Putin promised that, following victory, his forces would carry out the “de-Nazification” of Ukraine. The implication was that the current government – headed by a Jewish President with three uncles who died in the Holocaust – is wholly or partly Nazi.

This is not the first time that the Kremlin has used the term “Nazi” to describe Ukrainian authorities. It is not even the fiftieth time. For years, Russian officials and state media outlets have used the term to smear and demonise Ukraine and its government. Just in the past few weeks and months, Russian outlets accused Ukraine of being fascist, claimed that “state terror” in Ukraine is comparable to the Nazi occupation, and alleged that “fascist forces” organised Ukraine’s 2014 Maidan Revolution.

“Nazi east, Nazi west, Nazi over the cuckoo’s nest”

Back in 2017, we examined the frequent accusations of who is a Nazi according to the Kremlin. There were many already back then. Russian state media and pro-Kremlin outlets have long labelled anyone deemed hostile to Russia or the geopolitical project of uniting the Russian-speaking world, or Russkiy Mir, a Nazi or Nazi sympathiser, in particular Poland and the Baltic states. Even Italy has not escaped Nazi-related terminology such as “Gestapo”. We could go on, and on, and on. Our database has more than 800 entries with “Nazi” as keyword.

What is different now?

Two elements: “Nazi” has now become dominant in state outlets. From being merely frequent and directed at selected countries – Ukraine, the Baltic states, Poland – it has now become a general obsession. According to RT, the entire Europe [EU] is generally like Nazis. Secondly, now it also dominates Putin’s vocabulary – together with other derogatory terms such as “nationalist drug addicts”, “puppets”, etc. In recent months, even Foreign Minister Lavrov could hardly utter a word about Ukraine without saying “Nazi”.

On 4 March, when the Russian parliament unanimously rubberstamped draconic laws curbing free speech and independent media, the “debate” was filled with the Nazi word. Ostensibly, the entire West is “Nazi” because of their support to Kyiv and for this support, 48 countries are now declared “unfriendly” towards Russia.

Motives

Such relentless lingo cannot have had the purpose of dividing Ukraine from within, or bringing foreign adversaries over to Putin’s side. In the face of such verbal assault – the rhetorical equivalent of exposing yourself on a crowded street – an opponent’s natural reaction is to close ranks against you before turning away in disgust.

Instead, Putin’s Nazi obsession likely has mostly conscious internal purposes. Like the schoolyard taunt mentioned above, Putin’s Nazi-baiting seeks to distract from the weaknesses of his own regime. It also attempts to unite a Russian domestic audience against a remorseless, demonic, and imaginary external enemy. Finally, it seeks to compel that domestic audience to fight – or, at least, not to object to the fight against – the conjured bogeyman.

The ideological basis and key identification marker for the modern Russian state is the victory over Nazism in 1945. During Putin’s rule, military parades have grown ever more pompous. Grassroots initiatives such as the “Immortal Regiment”, originally intended as an individual way to honour family member who fought in 1941-45, have been hijacked for all-purpose state shows to instil the right patriotic feelings in younger generations. Russian state TV now often broadcasts video trailers ahead of evening programmes featuring WW II veterans from the Leningrad siege, the defence of Moscow or similar historic events.

Now, this War – “de-Nazification”

Putin’s claim of wanting the “de-Nazification” of Ukraine, however, may have one external purpose: smearing all Ukrainian nationalists as Nazis. The Kremlin’s giant problem is that its invasion has energised Ukrainian national pride and resolve in a way that few other actions could have done.

If the Kremlin manages to win the ugliest of victories in Ukraine, “de-Nazification” within the country could be even uglier. Would anyone expressing Ukrainian pride need to be “de-Nazified”? One shudders to imagine.

“De-Nazification” is an Orwellian euphemism for a purge of elected officials and the administration of an independent country.

In a Stalinist-style action, the recent arrests and abductions of Ukrainian mayors in Russian-occupied cities illustrate how Kremlin puppets are installed. If in doubt about how Putin handles political opponents, one can look to Alexei Navalny. Or again, check his speech of 16 March to mobilise patriotic moral. Beside the “de-Nazification”, Putin also described domestic opposition as “traitors, against Russia; the West’s 5th column; dirty insects to be destroyed”.

The artificial, Nazi state

For years, Putin has made no secret of his conviction that Ukraine is an artificial state and the country belongs inside Russia – see his long article from July 2021. Putin insists his descriptions are true, they must be Nazis, like schoolyard bullies who insist that a weaker child somehow deserved to be beaten. His descriptions only makes sense in the realm of his truth, a version ideologically described by Kremlin philosopher Aleksander Dugin which only he and other radical Russian nationalists can believe.

This has nothing to do with facts. Far-right groups had a very limited presence during the 2014 Maidan protests and went on to obtain abysmal results in the 2014 presidential and parliamentary elections in Ukraine. During the 2019 election cycle, the far-right sustained an even more tremendous failure: no representation at all in the parliament.

When autocrats chase geopolitical ideals such as establishing Russian sovereignty over allegedly historical Russian territories, the yawning void that separates an ideal from reality can become a disaster. We see the results today: Russian bombardments of civilian targets across Ukraine.

The Cult of personality…

While Putin blame others for being Nazis, the cult of personality grows at home.

18 March marked the 8th year since the illegal annexation of Crimea. The celebrations in Moscow reached a new climax this year. On that day, Putin spoke at the Luzhniki stadium in Moscow, where full tribunes could see him standing by the slogan “For a world without Nazism”. Cynically, he was justifying war again with two most used words to justify the invasion on Ukraine: genocide and Nazism.

Approximately 100,000 people participated in the concert, many of them with banners and slogans: “For the President”, “For Russia” “For Crimea”, “For Donbas”. The “for” – “za” of course spelled with the Latin first letter “Z” to hail the war.

It is difficult not to see the cult of personality, too well known from former times of war.