On November 11 Latvia’s parliament, the Saeima banned the use of the Russian St. George ribbon in public events. One of the reasons for the ban is Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. Russian media reacted to Latvia’s decision by pulling out all the classics of its antinationalist arsenal, raising the alarm about “repression against Russian speakers”, Russophobia and fascism in Ukraine and in Latvia.

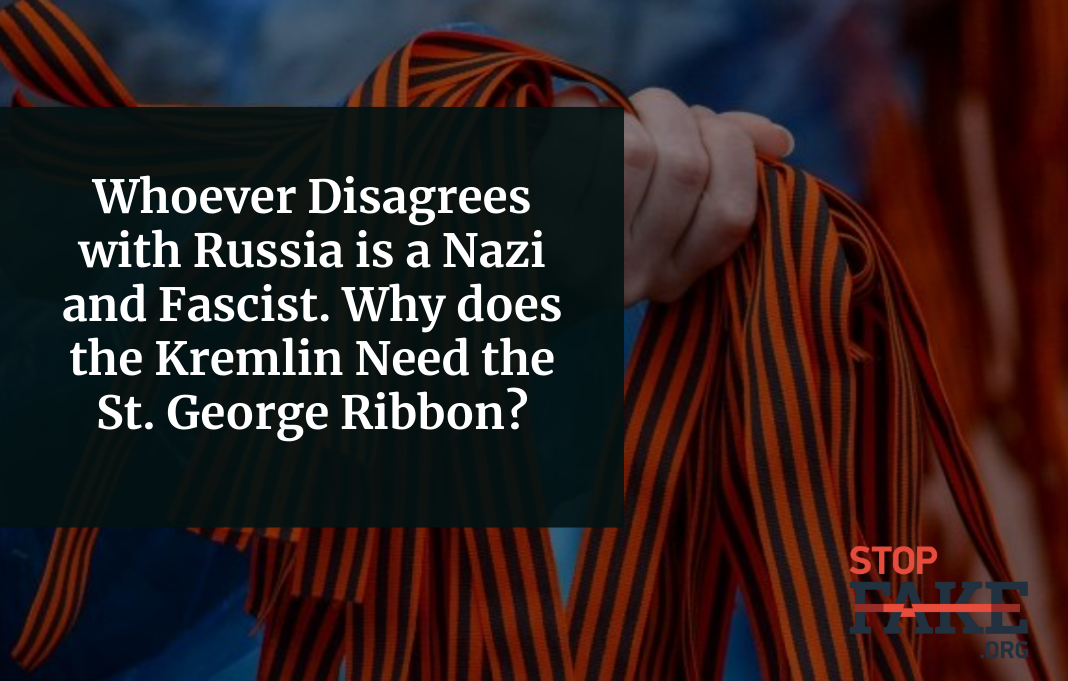

For Russia today the St. George ribbon, a black and orange bicolor pattern, is a symbol of victory in WWII, but for Russia’s neighbors the ribbon is a sign of imperialism and Russian chauvinism. Originally the ribbon was a part of the Order of St. George the highest imperial military award introduced by Catherine the Great in the 18th century and abolished after the Revolution in 1917. The St. George’s ribbon did not exist during WWII and was revived only in 2000, when Russia reintroduced the order.

A symbol of peace throughout the world

After Latvia moved to ban the ribbon, Russian media began a whitewashing campaign, claiming the ribbon had a deep symbolic meaning. Claiming that radicals were always picking on peaceful symbols, Kremlin talking heads energetically opined about the peaceful and friendly Russians using the ribbon to honor the past.

What exactly are the objectionable values that this symbol represents? Courage? The fight against Nazism? Love for your fellow man? I consider it a betrayal of memory and a distortion of history to appease political goals” writes Lenta.ru.

Hate has its own laws. The St. George ribbon has joined the detailed list of Soviet and Nazi symbols banned at public rallies. The saddest thing is that this ribbon does not belong to these symbols” writes Russky Mir.

The St. George ribbon has become a symbol of resistance, a uniting symbol of people who are fighting for their rights against neofascist and Russophobic regimes. The hate demonstrated against the St. George ribbon in Kyiv and Riga is really a demonstration of the ribbon’s power” declares the Argumenty and Fakty newspaper.

Supporters of Russia’s neo-imperial policies around the world continue to be deprived of the ideological support for justifying the Kremlin’s aggression. The St. George ribbon is one such symbol explains Yana Prymachenko, a history PhD and senior researcher at the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences Institute of Ukrainian History.

“There was no St. George in the Soviet panoply of awards, but during World War II Stalin began using Russian imperial symbols and rhetoric, returning the rank of guards and introducing the Order of Glory in November, 1943, an order which stylistically was very reminiscent of the St. George Cross and using the same colors. During the Russian empire the St. George Cross was quite popular among the people and recipients of the order were treated with deep respect. The same became true for the recipients of the Order of Glory in the Soviet Union. This award was so popular because it was awarded to ordinary soldiers or lower rank officers and the Order was awarded only for battlefield performance, in that regard its was a sacred award,” explains Yana Prymachenko.

That is why the Kremlin was so furious by the Latvian ban of the St. George ribbon, because Russia had devoted great effort to turn a symbol of Russian military valor and courage into a friend or foe marker in the Russian sphere.

“Since 2005 Russia has gradually combined the symbolism of the St. George ribbon with the Order of Glory turning it into a universal symbol that combines Russian imperial military past and the Soviet military past with the central event in Russian history – World War II. In the Russian historical calendar World War II is the main event, the main historical holiday and of course an instrument for spreading influence over the post-Soviet space” says Dr. Prymachenko.

Rewriting history is another persistent narrative that Russian media use constantly. Reflecting on the “catastrophic consequences for world history” from Latvia’s decision, the newspaper Vzglyad expresses “spiritual pain for Russians” in Latvia. “It looks so cowardly to poop under your neighbor’s door and then proudly look around” the newspaper declares.

NewsFront took the outrage to another level, claiming that Latvia’s decision was aimed at the erasing Russian nationality. “The specific political goal set by the radical nationalists is to deprive the Russian inhabitants of the country of their historical memory and thereby facilitate the process of assimilation of children from Russian families,” the publication declared.

Historian Yana Prymachenko explains that such tactics have long been tried in Ukraine. The Kremlin used similar narratives back in 2017 when Ukraine introduced a ban of the St. George ribbon. Russian media then claimed that Ukraine had “abandoned its past” and was “denying its common history”. Now these same narratives are being used against Latvia.

“It should be noted that with the annexation of Crimea and the beginning of Russian aggression in Donbas, the St. George ribbon as a universal symbol has lost its meaning. The ribbon has become a symbol of the “Russian world”, Russian aggression and Russian neo-colonial politics. In 2014-2015, even Belarus refused it – then during the celebration of Victory Day in Belarus they replaced the St. George ribbon with apple blossoms. The ribbon is banned in Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan – that is, since 2014 we can say that the ribbon is no longer a symbol of World War II, but a symbol of Russian military aggression and expansion,” says Yana Primachenko.

Fascists and Russophobes all around

In contrast to the relatively new narrative about depriving people of their historic memory, the theme of Nazis and fascists was invented by the Kremlin propaganda machine back in Soviet times. This theme is eagerly supported by Crimean collaborators who raise the alarm about “fascist atrocities” in Ukraine, the EU and the US on a regular basis. The St. George’s ribbon ban in Latvia was no exception.

In an RT article Crimean “senator” Sergei Tsekov accused Latvia of not respecting history. “This is their kind of democracy … This is another indicator of Russophobia, visible in the policies pursued by today’s Latvia. After the collapse of the USSR, Latvia, it chose the Russophobic course, and is still adhering to it ” Tsekov said.

“The St. George’s ribbon is the banner of people who disagree with the manifestations of Nazism and the oppression of the Russian-speaking population. Latvia, one might say, leads the list of countries that create unbearable conditions for Russian-speaking citizens. The country today demonstrates a commitment to Western, and primarily American, democracy, and if it were given free rein, it would generally expel all Russian-speaking citizens,” RT quotes another Crimean collaborator,“ deputy Dmitry Belik.

“Latvia has very quickly become a forgetful country and very quickly has turned into an anti-Russian state, slipping to the level of barbaric nationalism” pro-Kremlin Crimean Tatar Ruslan Balbek told RT.

The narrative about “fascists” in power is an invention of the Soviet propaganda machine, it is the ideological work of the Soviet Union, says Yana Prymachenko. Dozens of years later, this thesis has been improved and modified, reinforced with accents, and spread again with the help of modern media and technologies.

“Back in Soviet times, there was a division into “your own” and “strangers”. The “strangers” were already perceived as something fascist. Do not forget that when Hitler came to power in Germany in 1933, it was the German National Socialist Workers’ Party. Stalin did not very much like that Hitler positioned himself as a socialist. Therefore, it was then that the labeling of Germany, the main opponent of the Soviet Union, as fascist began. During World War II, this delineation of “your own “and “strangers” became entrenched – for example, the Russian historian Nikita Sokolov jokes that no matter who Russia or the Soviet Union fought against, they would be Nazis and fascists. This is also a universal marker, because it is necessary to somehow demonize the enemy. This is a proven marker, which immediately has an appropriate response in society,” says Prymachenko.

Defend Russia the world over

Russia continues to shake the borders of the “Russian world”, considering almost every state on the political map of the world to be a sphere of its influence. Pro-Kremlin propagandists continue to advocate “for the protection of compatriots”, acting as of crusaders, bringing their ideology and faith in a “brotherly future” to the world. This tactic was also applied to Latvia – there, after the St. George ribbon ban, Russians “who must be protected” immediately appeared.

“Who benefits from exacerbating the already fragile interethnic relations in our republic? Many Latvian Russians may perceive this bill as a blow to their national dignity,” writes Sputnik.

“We will not give up defending and protecting the truth about the war, about the thousands of Soviet soldiers who saved Latvia and the whole world,” Baltnews quotes says Olga Amelchenkova, deputy of the Russian State Duma.

“The ban on the St. George ribbon by the Latvian parliament is a continuation of the rabid policy of Russophobia, alienation from Russia, discrimination against Russians on the territory of the country … The Russian Foreign Ministry should more actively advocate for compatriots, apply diplomatic measures, including political and economic sanctions and criminal prosecution of Russophobic politicians,” Baltija.eu quotes a member of the Presidential Council for the Development of Civil Society and Human Rights Alexander Brod.

All these statements fit into the classical concept of the “Russian world,” says historian Yana Prymachenko. Values such as Orthodoxy, language and “common history” constitute the backbone of the “spiritual bonds” of Russia modern ideology.

“The concept of the ‘Russian world’ is to spread Russian cultural identity and Russia insists that the Russian language, Orthodoxy and common historical memory are the tools for promoting Russian influence. And if we take the post-Soviet space, from the point of view of Moscow, the most common and least controversial event is precisely the victory over Nazism – the greatest evil in the world was overcome together,” explains Yana Prymachenko.

“Rewriting history”, “substitution of values”, “worship of Nazi ideology” – these are the epithets that pro-Kremlin media already use to describe any event that does not fit into the ideology of the “Russian world”. In principle, The Kremlin propaganda machine considers any Ukrainian or resident of another country who speaks the state language and believes that “the reunification of Crimea with Russia” and “the civil war in Donbass” are in fact the Russian occupation of Ukrainian territories and Russian aggression, a “Nazi”. In fact, it is the Kremlin that exploits history to advance the Russian political narrative for the sole purpose of its own military expansion.

Valeria Danko