This article is part of a larger guidebook by RuNet Echo to help people learn how to conduct open-source research on the Russian Internet. Explore the complete guidebook at the special project page.

Outside of the familiar English-language social networks of Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and too many more to name, there is a handful of social media platforms used either exclusively or primarily in the post-Soviet world. While the instructions and tips laid out here are meant specifically for Russia’s homegrown social networks, the general approach is the same for research conducted on any such website—especially regional networks.

Contents [hide]

- VKontakte (or VK, which means “In Contact”) is by far the most popular social network in Russia. The layout is basically the same as Facebook of years past, but with added quirks and a heavy dose of pirated content.

- Odnoklassniki (“Classmates”) is the second most popular platform in Russia. The demographics for this service tend to skew older than other services, but it’s still immensely popular.

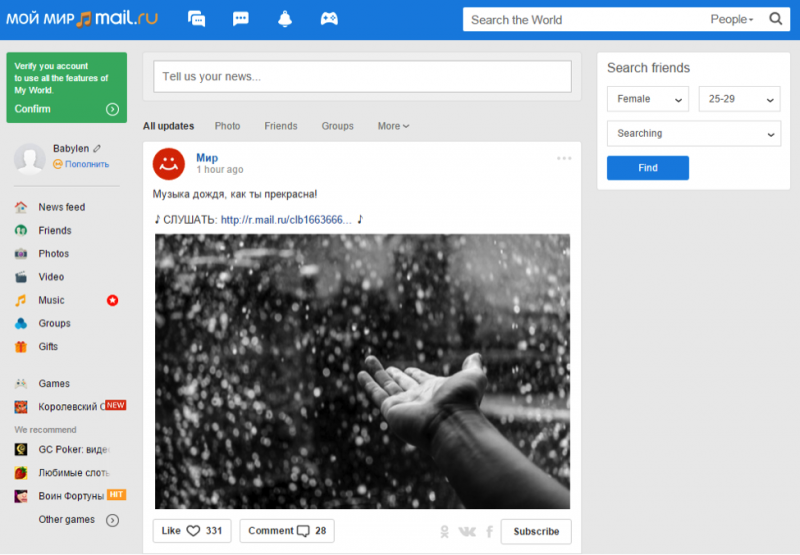

- Many Russians and Ukrainians also maintain profiles on Moi Mir (“My World”), a service operated by Mail.ru. Accessing information on a stranger’s Moi Mir account is more restricted than it is with the other services listed here.

VKontakte

VK is by far the most important and popular social network in Russia and Ukraine. The same is true in Belarus, Kazakhstan, and other Russian-speaking former Soviet states. In 2014, there were more than 60 million VK users in Russia, compared with only 10 million Facebook users. Learning the ins and outs of this social network is essential in conducting open-source research on the RuNet.

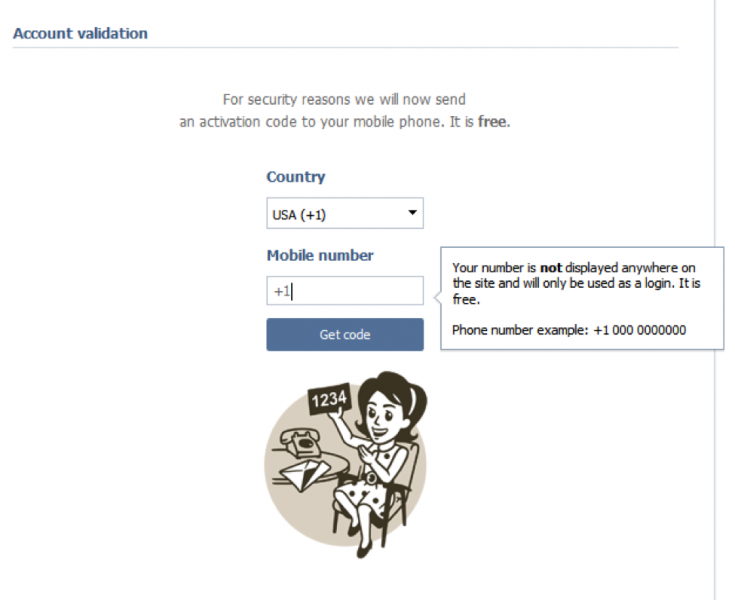

Because you need to have an account on VK to access much of the information available on the website, you should register an account, if you do not already have one. If you are using VK purely for monitoring and research, there is no need to enter your real name or personal details—all you need is a valid phone number to receive a confirmation SMS.

You must have a way to receive an SMS message to confirm your account.

You must have a way to receive an SMS message to confirm your account.

The account-setup process is very similar to Facebook’s, with user-inputted personal information, pictures, a place for “posts” (similar to a Facebook timeline), and a list of friends. Note some of the highlighted sections in the image below, which are of use when tracking Russian, Ukrainian, and separatist soldiers, for instance:

The account-setup process is very similar to Facebook’s, with user-inputted personal information, pictures, a place for “posts” (similar to a Facebook timeline), and a list of friends. Note some of the highlighted sections in the image below, which are of use when tracking Russian, Ukrainian, and separatist soldiers, for instance:

- In the top right, there is a “last login” feature, which is not on Facebook. There is no way to see the location of the last login, however.

- The military service information is also unique to VK, when compared to Facebook. Many soldiers and veterans will have numerous battalions and groups listed here. Russia has military conscription for young men, and many (but not all) men will have some military experience, whether it is listed on VK or not. Contract soldiers will often list multiple military units in which they served, possibly with both conscripted and contracted units. Additionally, soldiers will often join public groups for their military unit.

- Click “See All” next to photos to see all of a user’s albums and profile pictures in one place.

The search functions on VK are much more robust than on Facebook, and very easy to use. If you were to look for soldiers from Pskov, Russia serving in 2014, the search parameters below yield numerous results:

The search functions on VK are much more robust than on Facebook, and very easy to use. If you were to look for soldiers from Pskov, Russia serving in 2014, the search parameters below yield numerous results:

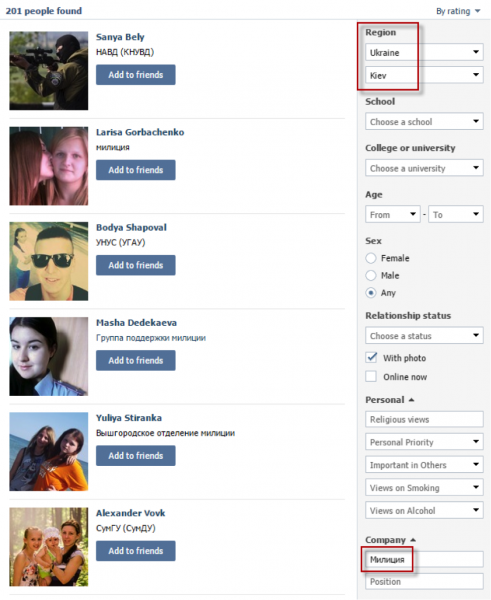

You can also use more advanced options in specific cases, to narrow your results to show just users with certain kinds of employment, military service, or education, past or present. For example, if you wanted to conduct research on corruption in Kyiv, you could search for specific job titles, such as civil clerks, police officers, judges, and so on, then scavenge the available open-source information to find signs of conspicuous wealth or lavish trips.

You can also use more advanced options in specific cases, to narrow your results to show just users with certain kinds of employment, military service, or education, past or present. For example, if you wanted to conduct research on corruption in Kyiv, you could search for specific job titles, such as civil clerks, police officers, judges, and so on, then scavenge the available open-source information to find signs of conspicuous wealth or lavish trips.

In the example below, the search parameters are set for residents of Kyiv who list “police” (милиция) in their employment field.

Of course, not every one of these results will be police officers. For example, one search result is someone who is part of the “Group for the Support of the Police,” and is likely not an actual police officer. Additionally, there are hundreds of other police officers who are simply not on VK, or did not list their job titles in searchable fields. If you’re looking for someone who isn’t discoverable using this kind of search, it’s important to track networks of contacts (partners, relatives, colleagues, and so on) who might provide more information for your research topic.

Of course, not every one of these results will be police officers. For example, one search result is someone who is part of the “Group for the Support of the Police,” and is likely not an actual police officer. Additionally, there are hundreds of other police officers who are simply not on VK, or did not list their job titles in searchable fields. If you’re looking for someone who isn’t discoverable using this kind of search, it’s important to track networks of contacts (partners, relatives, colleagues, and so on) who might provide more information for your research topic.

Odnoklassniki

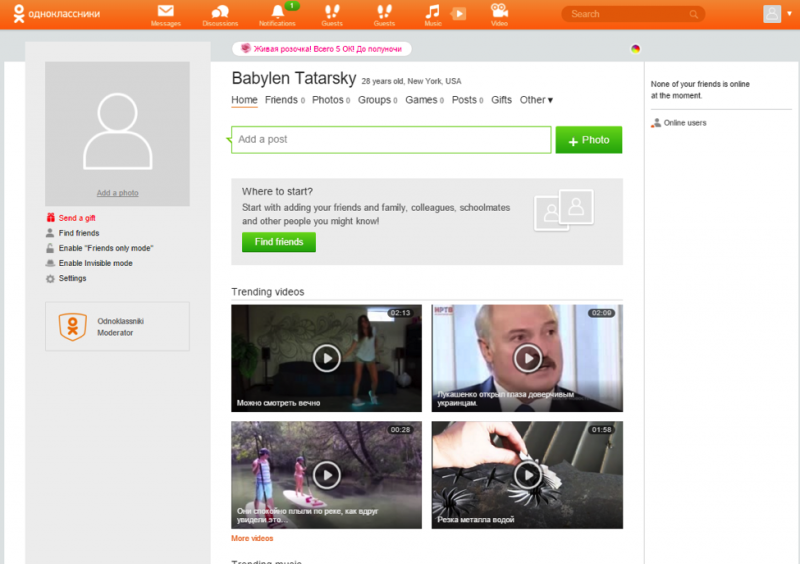

Odnoklassniki is the second-most popular social network in Russia. Like VKontakte, Odnoklassniki is very popular in post-Soviet, Russian-speaking countries, including Ukraine, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, and Georgia. In 2014, Odnoklassniki had around 40 million registered users in Russia and 65 million in total. The service’s users are typically older and more likely to be women than any other Russian social network.

Registering for Odnoklassniki is a bit easier than VK, since you do not need to provide SMS confirmation. However, unlocking extra account features requires SMS confirmation.

After registering, you will be greeted by the home page, which looks quite a bit different than VK (and, by extension, Facebook).

After registering, you will be greeted by the home page, which looks quite a bit different than VK (and, by extension, Facebook).

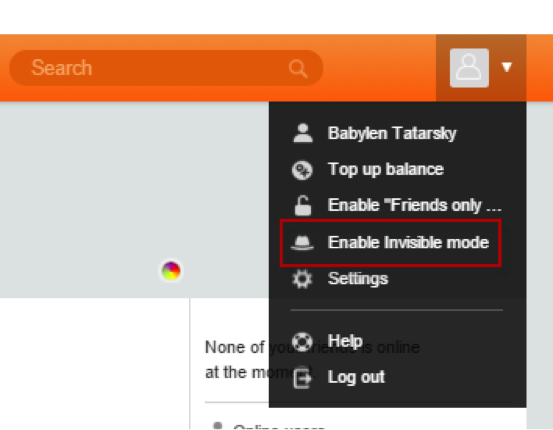

Odnoklassniki is unique among modern social networks in that it provides users with the identities of people who visit their accounts pages. Therefore, if you are trying to conduct a discreet open-source investigation, it is important either to search anonymously, or to “Enable Invisible Mode.”

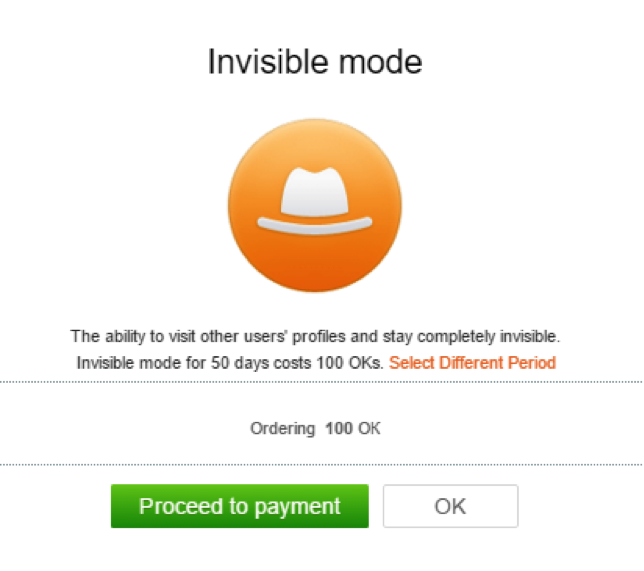

Odnoklassniki is unique among modern social networks in that it provides users with the identities of people who visit their accounts pages. Therefore, if you are trying to conduct a discreet open-source investigation, it is important either to search anonymously, or to “Enable Invisible Mode.” Browsing Odnoklassniki anonymously, however, is not free—it costs “OKs,” a sort of digital currency on the site.

Browsing Odnoklassniki anonymously, however, is not free—it costs “OKs,” a sort of digital currency on the site.

100 OKs, which allows 50 days of anonymous use, costs 100 rubles (not even $2). You can buy these credits with a variety of payment methods, including credit cards.

100 OKs, which allows 50 days of anonymous use, costs 100 rubles (not even $2). You can buy these credits with a variety of payment methods, including credit cards.

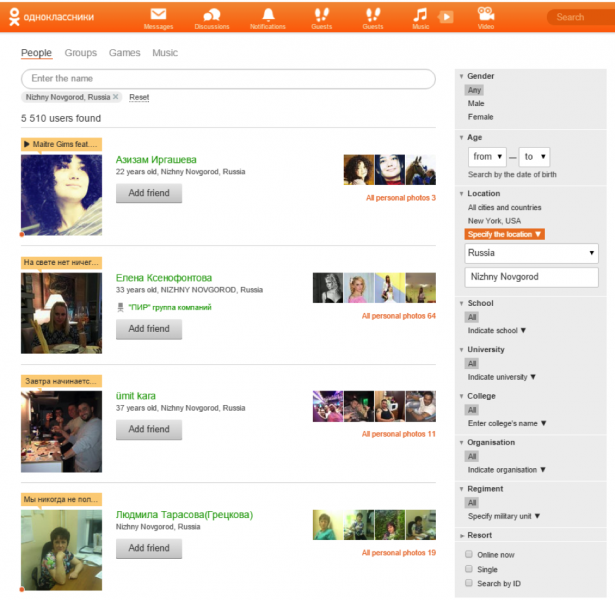

Like VK, Odnoklassniki has a robust set of search parameters:

Moi Mir

Moi Mir

The third-most popular Russian social network is Moi Mir, an offshoot of the Mail.ru web service, not unlike the relationship of Google+ to Gmail. As of 2014, Moi Mir had about 25 million Russian users—roughly the same number of active Russian Facebook users in the same year.

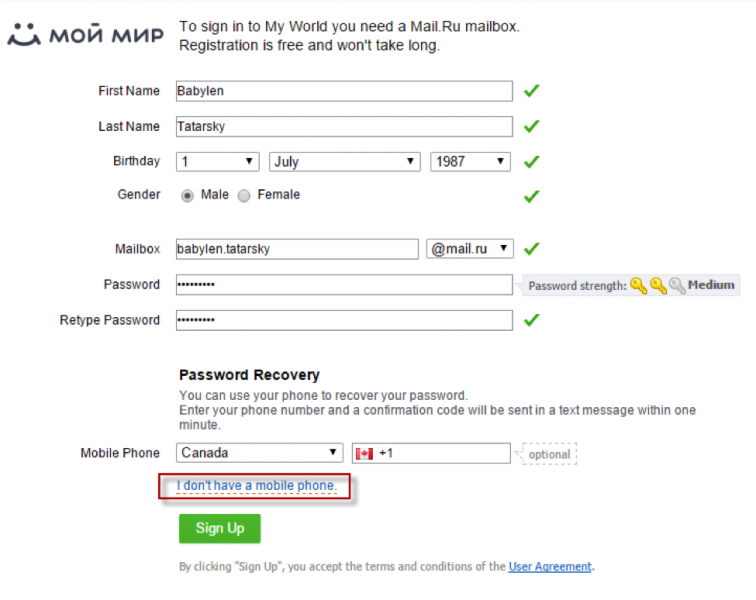

Moi Mir users set up their accounts through a Mail.ru e-mail address. As with Odnoklassniki, no SMS verification is required to complete registration on Moi Mir:

After selecting “Join now” on the signup screen, registration for a Moi Mir account is complete.

After selecting “Join now” on the signup screen, registration for a Moi Mir account is complete.

As with Odnoklassniki, optional account verification via SMS will unlock a Moi Mir account’s full features, but this isn’t necessary to use the site’s basic features.

As with Odnoklassniki, optional account verification via SMS will unlock a Moi Mir account’s full features, but this isn’t necessary to use the site’s basic features.

The search functionality of Moi Mir has many of the same features as VK and Odnoklassniki, but it is clearly aimed at being more of a dating site. Many of the search parameters are based on physical appearance, or (in what is likely unique for any social network) the user’s “Chronotype,” signifying when someone typically wakes up and goes to sleep.

As you can see from the screenshots above, you need to be able either to read Russian or to copy and paste in Russian city names to search users based on location, as the site is not accessible in English.

As you can see from the screenshots above, you need to be able either to read Russian or to copy and paste in Russian city names to search users based on location, as the site is not accessible in English.

***

These three social networks are the largest such websites specific to Russian and post-Soviet users, but Russians also use Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, and other sites. There has been continued Russian-language growth on these networks from all angles, whether we’re talking about the strong community of anti-Kremlin opposition users on Facebook, Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov’s infamous antics on Instagram, or popular pro-Kremlin Twitter accounts. If you want to conduct research using the networks with the largest numbers of ordinary Russian speakers, however, you need to gain some fluency in using VK, Odnoklassniki, and (to a lesser extent) Moi Mir.

Next week, the third installment to RuNet Echo’s guidebook will outline how to conduct open-source research in Russian, without speaking Russian.

By Aric Toler, Global Voices