Author: Anastasiia Grynko, PhD

Fieldwork and Coding: Artem Laptiiev

For ‘Stop Fake’

March 2019

Inroduction

News and news-making processes are no longer narrowly focused solely on media practices related to the simple exchange of information. In a growing number of cases it has become part of a proactive political and moreover, military strategy. Having been a part of the Soviet Union where the whole media system was centralised and controlled by Moscow, Ukraine faced manipulated information that the Kremlin widely applied in the form of propaganda. Manipulated information intensified again in 2014 when Ukraine was placed in the center of a hybrid war [1] facing not only military but also information attacks from Russia which took the form of fake news.

Fake news, or forgeries, have been widely defined as manipulative information in media on high-profile events that do “not correspond to reality[2]”. According to recent research, Russia’s propaganda messages today in many ways echo earlier Soviet propaganda patterns and therefore, disinformation actions taken by Russia should not be narrowed to the current moment and limited to the ongoing war in Ukraine [3].

To counteract the growing flow of propaganda and debunk fakes about events in Ukraine, in March 2014 Ukrainian journalists and media activists launched the Stopfake.org Project. StopFake fact-checkers investigate stories from media outlets and feature the ones that have been identified as falsificated [4]. Later this initative grew into an information hub specializing in examining and analyzing all aspects of Kremlin propaganda [5].

Fake Narratives in Previous Research

Previous research, based on Stop Fake’s data, identified key narratives embedded into fake news stories. Specifically, the messages refered to disinformation, promoted the narratives about Ukraine as a “Western-backed junta”(1), “fascist state’ (2), and “failed state” (3). They have also tended to depict Russia as “not a part of the occupation/war”, “legitimized annexation of Crimea and occupation of Donbass”, stated that “War in Ukraine is actually conducted by the US, NATO or private contractors”, and promoted the “Decline of Western support for Ukraine” (12), “Manipulated news on International organizations (13), spread disinformation about the “Disintegration of the EU” (14) and the “Decay of the US and West in general” .

The idea of this research has been motivated by the interest to look at the quality of Ukrainian media coverage under the conditions of a Hybrid war during the 2019 Presidential Elections. How do Ukrainian media and particularly, opposition ones cover political themes? What kinds of specific narratives do they produce and promote? These questions inspired two recent research projects on narratives around Ukraine and coverage of the presidential campaign. The first empirical research was focused on data from Ukrainian opposition TV channels and examined the ways fake narratives (re)shaped the content of talk shows on those channels during the election campaigns for president during 2018-2019 in Ukraine [6]. Based on content analysis, research found that opposition TV channels in Ukraine have been involved in dissimination of misleading and fake narratives related to Ukraine and Ukrainian authorities. Specifically, they tended to repeat the narrative of “failed state”, “poor, destroyed, ruined, not effective state”. Legitimating the annexation of Crimea and shifting the accent from war and Russia`s attack to “not effective government”, “dependency on Russia” and “lack of interest from the side of western countries and international organizations”.

Being mostly focused on fake narrattives, this research, however, applied very limited data on the quality of coverage of specific presidential candidates (further – candidates) and the fake narratives related to this coverage. It also focused on TV channels and did not provide insight regarding the work of other media. Therefore, to shed more light on the current quality of political media coverage in Ukraine in times of hybrid war and the presidential elections [7], this research has been limited to online news media coverage during the last weeks before the elections.

Research Purpose, Sample and Methodology

The purpose of this research was to exemine the ethics and quality of Ukrainian media’s news coverage, specifically, the coverage of the presidential campaign and and explore narratives around this coverage.

The research posed the following questions:

RQ1: How do Ukrainian media follow (or violate) ethics during coverage of presidential candidates?

RQ2: How has news coverage been influenced by the information war and specifically, what narratives have been set and promoted by online media in Ukraine?

RQ3: How did selected media outlets cover the election campaign in general, and each of the presidential candidates in particular?

The research applied a mixed method approach (quantitative and qualitative (thematic) content analysis), as it allowed getting insights on frequencies as well as obtaining a detailed understanding of themes and narratives in media texts.

The sample included two online media : https://vesti-ukr.com (further referred to as Vesti) and https://strana.ua (further- Strana) that position themselves as news media. All news produced by both media during the two weeks of the last month of the presidential campaign (from the 3d to the 17th of March 2019) were analysed.

The online media Vesti belongs to the media holding Vesti Ukraine that also includes the newspaper Vesti and website ubr.ua[8]; the owner of the Holding has been reported as one connected to a Donbass NGO [9]. Online media Strana provides no information about their ownership. However, recent investigations have presented evidence of its pro-Russian position and close relation with Russian media[10]. Also both media Vesti and Strana have been often referred to as opposition media and have been previousely critised for violating journalism ethics and in particular a lack of balance by media watchdog NGOs[11][12].

The data covered all news that mentioned elections, presidential campaingns, the political situation and at least one of the presidential candidates. A hybrid (deduction and induction methods) approach was applied to elobarate on a codebook for further analysis: some codes have been used based on previous investigations of TV talkshows and others have been developed as a result of pilot fieldwork and were mostly data-driven.

The data collection process included two blocks. The first block collected message that were identified as ones that contain a fake narrative. This block included 36 coded units on vesti.ua and 28 coded units on strana.ua. The second block involved the mentioning of candidates. In total, 370 mentionings were retrieved from Strana and 208 from Vesti).

Key Findings

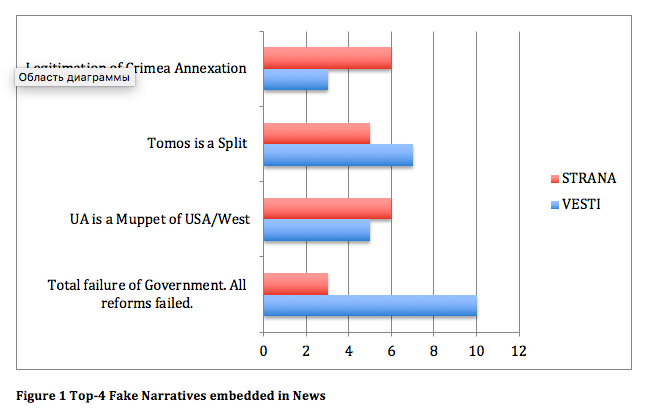

Content analysis of news produced by Vesti and Strana revealed 14 various narratives that were identified in previous research. Based on the data, the four following narratives were most often promoted by both media (Figure 1).

- “Failure of Government/ Reforms”. “Total Poverty”. This narrative has been mainly linked to the current government and reforms that have been often coined as a total failure: “pretending to be involved in the war, the government neglected real social problems, poverty, unavailable medical care, high process of food… people are exhausted”. Vesti has been the most active outlet promoting this message. Vest placed this message alongside emotionally appealing statements linked directly to social problems, particularly poverty and unpaid pensions: “none of the reforms lead to success, and moreover, left people completely poor”, “old and retired people have been robbed as their pensions are frozen”. Importantly, Vesti almost in all cases put this narrative opposite to comments made by presidential candidate Yuriy Boyko, one of the founders of the Opposition Platform.

- “Ukraine is a Puppet of USA/West”.

Another narrative widely promoted by both media underlined the dominating role of the USA and in some rare cases, other western countries that completely manipulate a dependable but weak Ukraine according to their “secret” interests. The news related to this narrative has been often presented as numerous opinion-like pieces presenting one-side of the story and therefore, could hardly be characterized as unbiased, neutral, and balanced:“ US Deputy Secretary of State arrived to Ukraine for political reasons. He will examine/inspect the candidates” (Headline of the news from 5 March, Strana.ua), “EU is ready to use Ukraine as a colony, an appendage for raw materials and cheap labor” (Vesti, news from 14 March).

- “Tomos is a Split” (and Flames the War).

Covering religious news, both online media tended to promote the narrative of Tomos as a dangerous split inside the church (and society) leading to escalated chaos and aggressiveness. In many cases starting from the headlines, Tomos has been presented as the instrument people in power use “to ignite the war”. The news related to this narrative presented among other things, stories about the “brutal capture of the church” and “radicals attacking citizens attending the Orthodox Church”.

- “Legitimizing the Annexation of Crimea”. The news promoting this narrative mainly applied a one-side opinion-like coverage presenting annexation as a “peaceful choice of people”. Here for example, the President of Belarus Olexander Lukashenko was quoted: “how many Ukrainians died to protect Crimea?… Zero… this means you all agreed it did not belong to Ukraine” (News, 40 March, Strana.ua). Thematic messages mention that Crimea will never return because it was exchanged for Ukraine’s membership in the EU and NATO.

Other Narratives

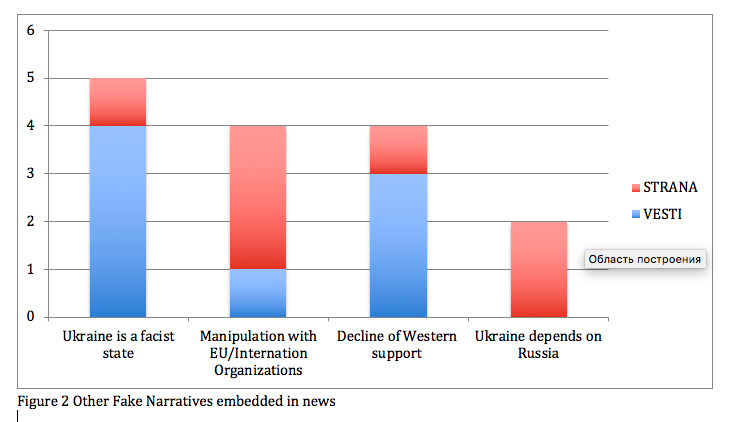

The research also indicated other fake narratives that appeared at least twice in the news from opposition online media (Figure 2):

- “Ukraine is a fascist state” (“they [the Government] intentionally grew up a band of nationalists decently naming them “activists” and giving them places in politics and in the information space,” “the government has done nothing to help internally displaced people….nobody is waiting for them in Ukraine governed by the current authorities.” ).

- “Decline of Western Support”, “West is not interested in Ukraine” (“France and Germany do not need [Ukraine to be a] more competent member, as it will dictate its conditions instead of accepting conditions of others”(14th March, Vesti).

- “Manipulations with EU and International Organizations” without providing the complete context: (“EU is ready to increase the quota on import of chicken breast from Ukraine….but EU will close the way Ukrainian Holding (МХП) whose owner is close to Poroshenko to avoid custom fees and export chicken for free to EU” (15th March, Strana).

- “Ukraine depends on Russia” and should negotiate (“Ukrainians` attitude to Russia improved….”, “Most Ukrainians wish peace with Russia and believe that only peaceful negotiations with Russia are possible…” (13th March Strana). “Ukraine should understand that while we are busy with our conflicts and problems, our neighbors are actively setting new agendas and looking for new models to cooperate with Russia. We should not be outside of this….” (3d March, Strana)

Other narratives that have been identified among those frequently set by opposition TV in previous research, have only be used once by one or both media in this investigation: “Total Poverty/Starvation in Ukraine” (15th March, Vesti, “pseudo-reforms have led to starvation in Ukraine”, 9 March, Strana.ua) and “Russia did not attack Ukraine ” (14 March, Vesti :“War is a [profitable] business..”).

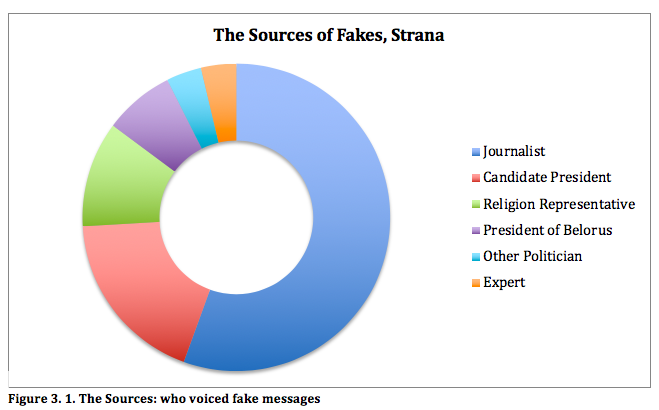

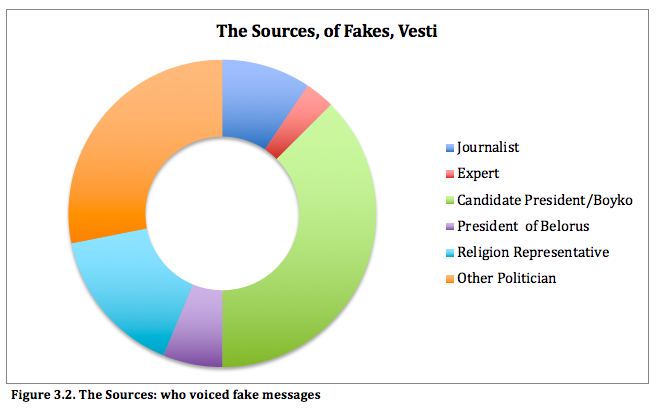

The Main Actors of Manipulations: Journalists and Opposition Candidates

Content analysis facilitated identifying actors promoting messages referred to as fakes (Figure 3.1 and Figure 3.1). Journalists who authored news on Strana.ua were found to be the most active actors setting fake narratives in headlines and texts. Vesti however, more often applied comments by candidates to promote fake messages with Yuriy Boyko leading the pact. Another candidate involved in placing fake narratives was Olexandr Solovyov (Party “Rozumna Syla” – “Розумна Сила”), placing fake in Vesti news. Strana.ua also cited candidates relating fake messages particularly, Ruslan Rygovanov, Yuriy Boyko and Olexandr Shevchenko.

Interestingly, the President of Belarus Lukashenko appeared a few times in the news of both media echoing statements related to already identified fake narratives. Other Politicians who were mentioned in news and contributed to setting fake messages were representatives of the party “Nashi” and its leader Yevhen Murayev (who were involved in communicating fake messages at least 7 times on Vesti).

Coverage of The Presidential Candidates: “Hero” Boyko vs “Antihero” Poroshenko

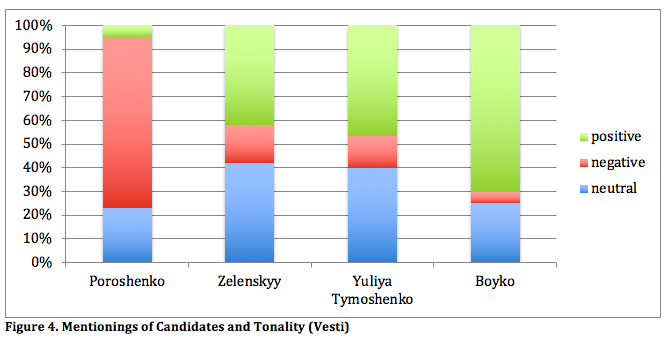

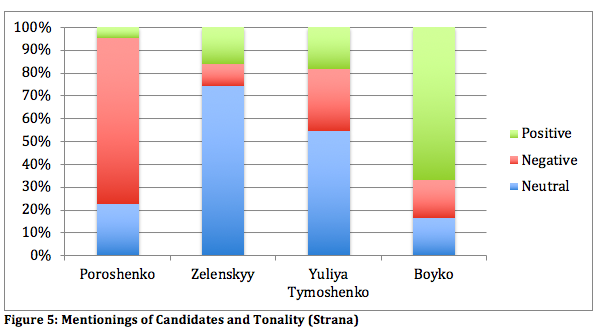

The data collected facilitated a closer analysis of how candidates were mentioned in the news and quality of coverage (and ethics). Finally, a significant number of news has been identified as not-balanced and biased, first and foremost, by the quantity of candidate mentions and their tone (Figures 4 and 5).

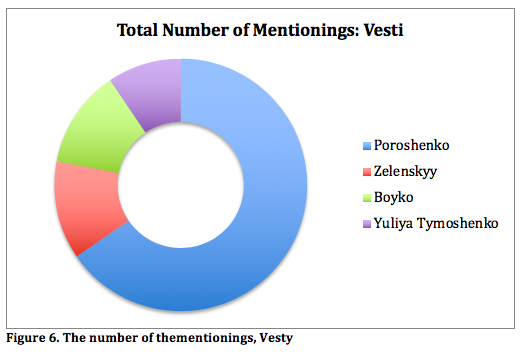

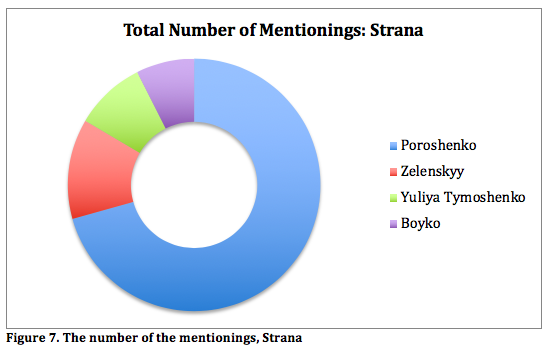

Based on content-analysis, Petro Poroshenko, Zelenskyy, Yulia Tymoshenko and Yuriy Boyko have been in the top 4 in terms of quanitity of mentions in news stories during the time interval of this research.

However, the research found dramatic differences in the numbers and ways each of the top 4 candidates were covered. The current President Poroshenko has been mentioned much more often than the other three competitors by both media (Figures 6 and 7) and in most of the cases with a clearly negative tone (Figures 4 and 5). For instance, the total number of references to Porshenko in the news by Strana exceeded 171 and 124 of which were identified as negative. Meanwhile the same media mentioned Zelenskyy only 31 times during the same time interval, Yuliya Tymoshenko was mentioned 22 times and Boyko mentioned 18 times. A similar trend was demonstrated by Vesti. Poroshenko recieved 104 mentions in the news 75 of which were identified as negative. Zelenskyy however, recieved only 30 mentions (with only 3 defined having a negative tone), Yulia Tymoshenko – 15 (with only 2 negative) and Boyko 20 (with only 1 defined as negative).

Therefore based on the data, Poroshenko has been the most frequently associated with negative-toned messages related to the already mentioned narrative of a failed state, a failed goverment and total poverty. Vesti were especially active in placing negative-toned messages. For instance, it produced a whole serie of regular negative-toned one-sided news devoted to Poroshenko’s trips around Ukraine to meet the voters.

Interstingly, negative-tones and biases have been mainly indentified in the texts of the healdlines and leads providing less information, presenting to lesser extent neutral and mostly emotional and opinion messages. For example, the Headlines : “the meeting failed, the activists sent Poroshenko to heaven” , “awful traffic near Kyiv: thousands of people are brought in buses to meeting with Poroshenko”, “Volyn students were forced to come to the meeting with Poroshenko”.

Other negative-toned unbalanced messages that mentioned the other candidates were also found in Headlines and/or Leads, for instance: “There will be no reason to laugh. Western media evaluated the chance of Zelensyy to win”, “We won`t stay calm until we reach the goal. The talk between people with voices of Tymoshenko and Kolomoyskyy goes online” , “Car wash near Kyiv trolled Poroshenko and Zelenskyy by its advertising. Photos”. In many cases the newsworthiness of some messages was also identified as questionable.

The leader of positive coverage in news by Vesti and Strana was opposition candidate Boyko, who recieved the biggest number of positive mentions by both media. The news stories covering him have often been produced from a one sided angle, providing claims without background. For instance, presenting the text of candidate Boyko’s appeal to voters as a news story. In many cases they also included criticism of the current president and presented Boyko`s promises to “make peace”, and “take care of retired people and other socially vulnerable groups”.

The four mentioned candidates, however, were not the only covered by both media. Significanlty less, but still a significantly large number of mentions about

Murayev (mostly positive), Vilkul (mostly positive), Bohomolets (mostly positive), Lyashko (mostly positive), Taruta (mostly positive), Sadovyy (mostly neutral), Gnap (mostly neutral), Hrytsenko (mostly negative), Kryvonos (mostly positive), Rygovanov (mostly positive), Solovyov (mostly neutral) and few others.

Generally Strana was identified as media producing more neutral and balanced news around the presidential campaign compared to Vesti. Among the cases that should be mentioned, Strana had published the series of materials presenting the programs of different candidates giving equal space to each candidate enabling the reader to get familiar with other candidates’ programs.

Conclusions

- Generally the content analysis indeintified similar narratives promoted by online opposition media and previousely investigated opposition TV[13]. Specifically, the narratives of “Failed State”, “Failed Goverment”, “Total Ruin and Poverty”, “Legitimation of Annexation of Crimea” as well as the narratives of the “Decline of Western Support”, “Manipulations with Western Countries” and “International organizations” and moreover total “Dependence on Russia” and the “Need to negotiate with Russia” were noticed in the coverage of both TV and online media before the elections.

- However, online media gave much more attention to the theme of Tomos, supporting the narrative of “Tomos as a Split.” Online media were also more active in promoting the image of Ukraine as a totally manipulated Puppet of USA (and other western players) “who lead Ukrainian politics in line with their interests”.

- Similar to TV channels, the themes related to Russia’s Invasion and War, Ukrainian Army, Volunteer Battalions have not been identified as popular themes covered by opposition news media in March.

- “Failed Country”, “Failed Government” and “Total Poverty”. Similar to the previouly investigated opposition TV chananels[14], the narrative of the failed/ruined country, failed reforms and failed goverment have been identified as top popular themes set by online media Vesti and Strana. As in the case of TV channels, the narratives closely related to the themes of total poverty, growing social disaster and, finally, turned into the criticism of current goverment. Online media however, often placed this narrrative in opposition to the positively toned coverage of other candidates and in a predominant number of cases

- Journalists and opposition candidates have been identified as the main actors voicing narratives related to fakes. Written by journalists headlines and leads of the news have been identified as the most popular areas of biased and manupulative messages. This finding differs from the one obtained as a result of TV talk shows content analysis where opposition politicians and invited expters were the most active in voicing the messages identified as fakes.

- Imbalanced Coverage. Number of mentions. The data indicated violations of new media standards and numerous cases of one-side and non-balanced news coverage of presidential candidates. The imbalances first, concerned the number of times each candidate was mentioned in news. Based on the data, Poroshenko was the most frequently mentioned by both media. Much less, but still significant, number was recieved by Zelenskyy, Yulia Tymoshenko and Boyko.

- Imbalanced Coverage. Tone: “Heros” and “Antihero”. Other evidence of ethical violations concerned less neutral and more opinionated coverage of news stories. Content analysis allowed the investigate the tone of the messages and indentifed “heros” and “antiheros” as they were presented by Vesti and Strana. Specifically, Poroshenko has been mentioned in negatively toned messages in a predominant number of cases by both media. However, very few (compared to other candidates) number of mentions that could be identified as neutral or positively-toned. On the contarary, the candidate Boyko has received predominantly positive coverage with very rare cases of critisism or neutral coverage.

Limitations and Future Research

This research expanded the previous investigation on quality of media coverage in times of presidential elections and also contributed to an understanding of how opposition media deal with the challenges of hybrid war in Ukraine. This study provided some valuable empirical evidence and revealed some similar narratives promoted by Ukrainian online media and TV channels.

However, due to the exploratory nature of this research as well as limited time and other resources, it has been confined to only two media and a one month interval. Future investigations could pursue more comparative goals, involve other types and formats of media, including media that work inside and outside of Ukraine as well as Ukrainian regional media outlets into the sample. It could also engage both textual and visual data to investigate and compare the strategies of settiong manipulative messages and narratives across various media and geographies.

[1] Esipova N. & Ray J. Information Wars. Ukraine and the West vs. Russia and the Rest. Harvard International Review. May 6, 2016. http://hir.harvard.edu/article/?a=13043

[2]Stop Fake. https://www.stopfake.org/en/how-to-identity-a-fake/

[3] Fedchenko. Y. ‘Kremlin Propaganda: Soviet Active Measures by Other Means’. Estonian Journal of Military Studies, Volume 2, 2016, pp. 140–169

[4] Kramer A. To Battle Fake News, Ukrainian Show Features Nothing but Lies. New York Times. February 26, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/26/world/europe/ukraine-kiev-fake-news.html

[5] Stop Fake. https://www.stopfake.org/en/about-us/

[6] Grynko, A. Fake Narratives in Times of Presidential Elections: How Hybrid War Reshapes the Agenda of Ukrainian TV. https://www.stopfake.org/en/fake-narratives-in-times-of-presidential-elections-how-hybrid-war-reshapes-the-agenda-of-ukrainian-tv/

[7] More on the challenges for media in times of elections and information war: https://www.stopfake.org/en/fake-narratives-in-times-of-presidential-elections-how-hybrid-war-reshapes-the-agenda-of-ukrainian-tv/ (Part “Media, Fakes, and Elections”)

[8] Vesti. Official website: http://vestiukraine.com/ru/holding/about.html

[9] http://www.theinsider.ua/infographics/2014/2015_smi/vlasnyky.html

[10] http://texty.org.ua/d/2018/mnews/

[11] https://detector.media/infospace/article/141984/2018-10-23-liderami-antireitingu-novin-stali-kpru-from-ua-znajua-politeka-stranaua-vestiru-doslidzhennya-imi-ta-tekstiv/

[12] https://imi.org.ua/en/news/imi-research-obozrevatel-and-strana-ua-have-the-largest-share-of-news-with-violations-of-journalism-standards-ukrinform-has-the-smallest-share/

[13] Grynko, A. Fake Narratives in Times of Presidential Elections: How Hybrid War Reshapes the Agenda of Ukrainian TV. https://www.stopfake.org/en/fake-narratives-in-times-of-presidential-elections-how-hybrid-war-reshapes-the-agenda-of-ukrainian-tv/