By Christo Grozev, Bellingcat

This is part I of our joint investigation with the Russian investigative magazine The Insider into a series of active measures, hybrid warfare and false-flag operations in the countries of the Balkans that appear to have been orchestrated by Russian individuals in close coordination with the Kremlin. You can read the Russian version of this part of the investigation here.***Bosnia and Herzegovina, September/October 2014:

On 2 October 2014, a short announcement appeared on the website of the Border Police of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The matter-of-fact alert was titled “Entry of nationals of the Russian Federation” and read:

“In order to objectively inform the public on the entry of citizens of the Russian Federation in Bosnia and Herzegovina, we inform you that in the period from 25 September to 2 October 2014, 144 citizen of the Russian Federation entered the republic via the International border crossing of Raca, as follows: on 25.09 (11 persons), 26.09. (36 persons), 27.09 (24 persons), 28.09 (24 persons), 29.09 (5 persons), 30.09 (40 persons) and 1.10 (4 persons). All persons satisfied the requirements for entry into Bosnia and Herzegovina, were not wearing uniforms and military artefacts, and among them were women and men of different age groups.”

This odd news item was the police’s attempt at calming the public, after local media had reported an unusual number of burly Russian men, all dressed in Cossack uniform, popping up in the tiny Balkan country in the weeks leading up to presidential elections on October 12. More alarmingly, the nation’s Federal TV had identified some of the Cossack visitors – in particular their leader, Nikolay Djakonov, as having led a paramilitary Cossack unit during the accession of Crimea earlier that year.

Now, more than a hundred of these same men, wearing the same uniforms, were all heading to Banja Luka, capital of Republika Srpska – the 1.2 m-people, Serb-majority entity that together with the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, makes up the state of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The purported reason for the Cossacks’ arrival was to take part in a folklore performance on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the start of the First World War. However, local media quickly discovered that none of the sheep-skin hatted dancers seemed to know when the planned performances were going to be, nor how long they planned to stay in the country. Nor, for that matter, could they dance. The Cossack delegation was accompanied by knyaz Zurab Zhavchavadze, the monarchist son of a former Russian Imperial Guard commander, and director of the Russian charity fund Basil the Great. The fund, along with the RS Ministry of Culture, were the official organizers of the Cossacks’ visit to the Federation.

Now, more than a hundred of these same men, wearing the same uniforms, were all heading to Banja Luka, capital of Republika Srpska – the 1.2 m-people, Serb-majority entity that together with the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, makes up the state of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The purported reason for the Cossacks’ arrival was to take part in a folklore performance on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the start of the First World War. However, local media quickly discovered that none of the sheep-skin hatted dancers seemed to know when the planned performances were going to be, nor how long they planned to stay in the country. Nor, for that matter, could they dance. The Cossack delegation was accompanied by knyaz Zurab Zhavchavadze, the monarchist son of a former Russian Imperial Guard commander, and director of the Russian charity fund Basil the Great. The fund, along with the RS Ministry of Culture, were the official organizers of the Cossacks’ visit to the Federation.

The Ministry of interior of the Republika Srpska had recommended to the Cossacks not to register as visitors with the Bosnian-Herzegovina authorities, but to make their way quickly to Banja Luka. Some of the arriving Cossacks crossed the border in vehicles owned by Republika Srpska special police forces, and were stationed at the special police training barracks in Laktasi, near Banja Luka. The public behavior of the men was also reminiscent of that of the so-called “polite people” popping up in Crimea in the weeks before the annexation – they made their presence ostentatious but refused to talk to the media. The only person who responded to media questions was their leader Djakonov. “We are not spetznaz”, he said to TV cameras with a smile, “We just don’t like media attention”.

The Ministry of interior of the Republika Srpska had recommended to the Cossacks not to register as visitors with the Bosnian-Herzegovina authorities, but to make their way quickly to Banja Luka. Some of the arriving Cossacks crossed the border in vehicles owned by Republika Srpska special police forces, and were stationed at the special police training barracks in Laktasi, near Banja Luka. The public behavior of the men was also reminiscent of that of the so-called “polite people” popping up in Crimea in the weeks before the annexation – they made their presence ostentatious but refused to talk to the media. The only person who responded to media questions was their leader Djakonov. “We are not spetznaz”, he said to TV cameras with a smile, “We just don’t like media attention”.

The nationalist, outspokenly pro-Russian president of Republika Srpska, Milorad Dodik, had recently declared his intent to hold a secession referendum in case he wins the elections. Just two weeks earlier, he had travelled to Moscow to meet with Vladimir Putin. In a public transcript of their Sept. 18 meeting, Putin had declared his unqualified political support for Dodik, and promised to defend Republika Srpska from unidentified “disrupters” of the Dayton accord. During the visit, Gazprom signed an agreement with Republika Srpska (“RS”) – bypassing the central Sarajevo government – for linking the republic to the ill-fated South Stream, then still in the proverbial pipeline. Dodik, in turn, thanked Putin for the meeting – their second one in 2014, with a third one coming up shortly in Belgrade just days before the RS election – and promised Putin the republic’s unqualified support for Russia. “We may be small, but our voice is loud”, said Dodik. A loud, pro-Russian European voice in the months following Crimea’s annexation was a rare commodity, and Russia treasured each one it could get. Pre-election polls in Republika Srpska were indecisive, with the chances equally split between the pro-Russian, separatist Dodik, and opposition leader Ognjen Tadic, who was running on a platform for change and against separatism.

On election day, Oct 12th, after casting his vote for himself at 15:10, Milorad Dodik was driven directly to the secluded posh Kalderra Hotel, a 15-minute ride from Banja Luka. There, he met his wealthy and influential Russian guest. That guest had arrived to Republika Srpska to make sure that elections went the right way for Russia; and he had the right experience for the job. He had planned, prepared and funded three referendums abroad earlier that year – in Crimea, Donetsk and Lugansk – and they had all turned out as required. And in each case, the Cossacks currently loitering the streets of Banja Luka had been a key component of his plan. His name was Konstantin Malofeev.

Five months earlier that year, Malofeev was placed on the EU sanction list for his material support for the separatist insurgency in Eastern Ukraine. He had been one of the initial ideologues and organizers of the annexation of Crimea, and had recruited, financed and supervised at least two of the key on-the-ground Russian mercenaries and leaders of the separatist insurgency in Eastern Ukraine – Col. Igor Girkin and Alexander Boroday. While all of Malofeev’s initiatives in Ukraine were, formally, privately organized and funded, intercepted phone calls between him and his lieutenants on the ground in Ukraine, as well as hacked email correspondence, showed that he closely coordinated his actions with the Kremlin, at times via the powerful Orthodox priest Bishop Tikhon whom Malofeev and Putin (in their own words) share as spiritual adviser; at other times via direct coordination between Malofeev and Putin’s advisers Surkov and Glazyev, but also via Malofeev’s close collaboration with RISS – the Kremlin-owned Russian Institute for Strategic Studies, chaired by former KGB/SVR Gen. Leonid Reshetnikov. In addition, a recent email hack that we have reviewed suggests that at least one employee of Malofeev’s participated in non-public sessions of the Russian government.

By mid-2014, a clear pattern had emerged: the Kremlin used Malofeev as the initiator and proxy-funder of active measures – including military special operations – in Ukraine, providing full deniability to Russia in case the operation failed. In case the operation succeeded – as was the case with Crimea – the Kremlin would ultimately take credit.

By October 2014, the time had come to test this private-public partnership further from home, in Republika Srpska.

Malofeev’s charity fund, in coordination with Dodik, organized the Cossack’s “commemoration” trip. In response to media questions, the Russian embassy in Sarajevo said it was not competent to comment on the Cossacks’ visit, providing a cloak of deniability. Malofeev sent his close associate, Knyaz Zhavchavadze, to mind the paramilitary group in Banja Luka.

Fifteen years earlier, Zhavchavadze had mentored the then teen-aged Malofeev during his entry into the Russian monarchist movement, and he was now running the billionaire’s Orthodox charity organization: Basil the Great Fund. Zhavchavadze had been involved in the preparation for the Crimea annexation and subsequent insurgency in Donbass, and, according to this interview, appears to have recommended Girkin to Malofeev for future undefined “joint efforts” back in 2013, based on lavish praise he had heard regarding Girkin from FSB generals during the Chechen wars in 1996-97, where Zhavchavadze claims to have travelled together with Bishop Tikhon.

On October 7th 2014, Alexander Dugin, the extreme-right, expansionist ideologue on Malofeev’s payroll who had played a key role in recruiting Russian volunteers for the war in Eastern Ukraine, emailed Malofeev a draft for an article in which he outlined Russia’s national interest in steering events in Republika Srpska towards Dodik’s victory, with a subsequent referendum for secession from Bosnia and Herzegovina, and ideally, (after overcoming Serbia’s president Vucic opposition) – unification with Serbia under the rule of the newly minted Serbian national hero Milorad Dodik. The article (which was discovered in a hack of Dugin’s emails in 2015) referred to the arrival of “polite Russian people” in Banja Luka ahead of the elections, and implied that their role was to prevent any unfriendly outcome from the elections. Dugin further prophesied that the expected secession and unification of Serbia would lead to upheaval and re-orientation towards Russia of other predominantly Christian-Orthodox countries in the region, such as Bulgaria, Romania, Macedonia and Greece.

Dugin’s warning was published in several Serbian-language and Russian websites in the days preceding the election, as was seen from Dugin’s emailed report on channels of dissemination on Oct 11., the day before the election.

Despite the assumed electoral impact of the meetings with Putin, the Cossacks loitering around Republika Srpska, and Dugin’s implicit warnings, the outcome of the elections in Republika Srpska was close. While the early vote count suggested a slim lead for Milorad Dodik by a few thousand votes, the final results would not be known until two weeks later.

Despite the assumed electoral impact of the meetings with Putin, the Cossacks loitering around Republika Srpska, and Dugin’s implicit warnings, the outcome of the elections in Republika Srpska was close. While the early vote count suggested a slim lead for Milorad Dodik by a few thousand votes, the final results would not be known until two weeks later.

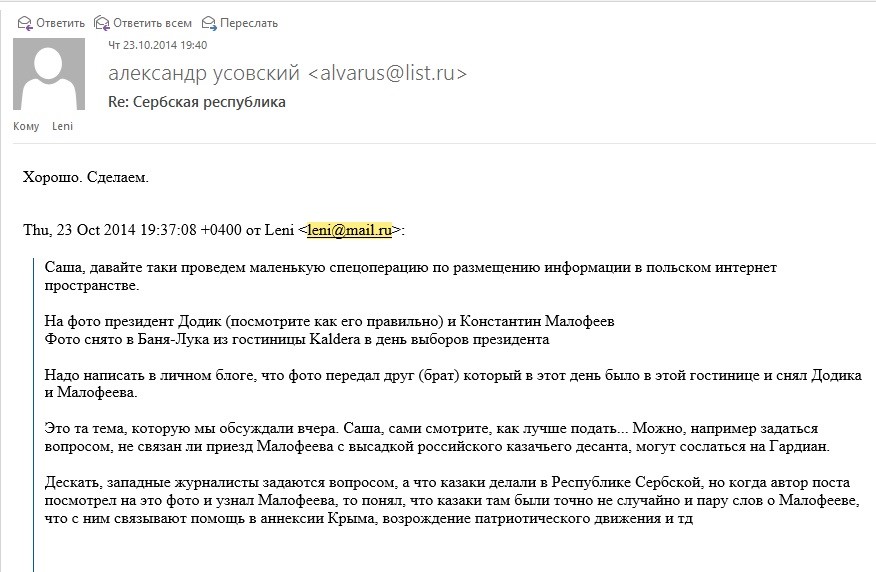

As seen in a recent mail dump leaked by Ukrainian hacker group CyberJunta, on October 23th 2014, Ms. Alena Sharoykina, publicly an anti-GMO activist and CEO of Malofeev’s TV channel Tsargrad TV, and privately Malofeev’s project manager for false-flag operations in Eastern Europe, emailed an urgent task to one of her agents whom Malofeev had been financing to plant disinformation and organize pro-Russian and anti-Ukraine rallies in CEE. The agent’s name was Alexandr Usovsky, a chronically penniless, Belarus-born struggling novelist, and member of a number of Russian extreme-right nationalist organizations (including the infamous NSO-North which was responsible for at least 27 hate-motivated murders”. Usovsky appears also closely linked to European Neo-Nazi parties, whose assistance he generously offered to Malofeev, who in turn was seeking for agents of influence (or proxies of disruption) in Europe. Usovsky frequently offered Malofeev the cooperation of the Polish neo-Nazi party OWP, Ľudová strana Naše Slovensko in Slovakia, as well as with the outlawed paramilitary arm of Jobbik in Hungary, Hungarian Guard. He often began his emails to his closer friends “Sieg Heil”.

Sharoykina’s email to Usovsky was titled “Republika Srpska”, and instructed Usovsky to conduct a “small special operation” – a controlled leak into the Polish news space of Malofeev’s secret hotel meeting with Dodik on election day.

The leaker was to imply the hypothesis that the billionaire’s arrival to Banja Luka was linked to the presence of Russian spetznaz in guise of Cossack dancers, and that he was there to oversee a Crimea-like scenario in case of negative electoral outcome. Sharoykina sent Usovsky the paparazzi-style photo of Malofeev and Dodik and asked that it be leaked as well.

Usovsky chose to distribute the message via his trusted contact Dawid Berezicki, functionary of the extreme-right anti-Semitic Polish People’s Party.

Usovsky reports back to Malofeev’s associate that he sent a proposed text for the leak, and asked him to choose ideally a “liberal blogger” as a leak destination.

What the motivation for this controlled leak was, is hard to determine with certainty. One possible explanation was that the outcome of the election was still uncertain, and Malofeev wanted to send one last warning shot that unless the slim gap in vote count is in Dodik’s favor, a Crimea scenario is ready to be activated. Another hypothesis, proposed to us by Alexander Sytin, former senior researcher at RISS, is that the leak was intended as a signal specifically to Poland, where at that moment both Malofeev and Putin’s adviser Surkov independently courted and funded pro-Russian politician Mateusz Piskorski. Yet a third hypothesis is that Malofeev was trying to raise his own profile vis-à-vis the Kremlin, and thus needed maximum “credit” given to his Republika Srpska role by foreign media.

What the motivation for this controlled leak was, is hard to determine with certainty. One possible explanation was that the outcome of the election was still uncertain, and Malofeev wanted to send one last warning shot that unless the slim gap in vote count is in Dodik’s favor, a Crimea scenario is ready to be activated. Another hypothesis, proposed to us by Alexander Sytin, former senior researcher at RISS, is that the leak was intended as a signal specifically to Poland, where at that moment both Malofeev and Putin’s adviser Surkov independently courted and funded pro-Russian politician Mateusz Piskorski. Yet a third hypothesis is that Malofeev was trying to raise his own profile vis-à-vis the Kremlin, and thus needed maximum “credit” given to his Republika Srpska role by foreign media.

Whatever the goal was, putting the Cossack dance troupe in action (other than the psychological impact of 143 menacing, uniformed Russian men roaming the streets on election day) was never required. On October 28th, the final vote tally showed that Dodik won the election by just under 7000 votes. Dodik thus retained control in Republika Srpska but lost the simultanous ellections at the state level, both in the election for the three-member presidency (where his candidate was defeated by the opposition leader Ivanic) and in the general election (where opposition parties narrowly overcame Dodik’s SNSD, and later joined the state level coalition). As a result, Dodik lost most of the influence he had before on state level institutions.

Bellingcat and The Insider separately attempted to obtain comments as to the purpose of the leaked emails – and the underlying intent of the Cossacks’ arrival to Banja Luka – from Ms. Sharoykina and Mr. Usovksy. Mr. Usovsy initially told Bellingcat that he never worked for, or received funding from Konstantin Malofeev to conduct pro-Russian false-flag activities or political engineering in Eastern Europe. He told Bellingcat that Mr. Malofeev was a “saint man whose only international activities are related to assisting the Orthodox church”. However, in an interview with The Insider, Usovsky did admit to receiving funding for operations in Central and Eastern Europe from Konstantin Malofeev “in the period May-October 2014”, and subsequently one small tranche from “Malofeev’s assistant”, presumably Sharoykina. Following 2015, Usovsky claims he was able to “scrape small donations” to assist his extreme-right friends in Europe from “various private high-profile individuals”. He declined to provide names, but his emails indicate that he tried to raise funding for pro-Russian political engineering in CEE from both Kremlin and Duma officials, and from private high-net worth individuals. In an illuminating exchange between Usovsky and Sharoykina, he asked her advice on whether to request funding from a particular Russian entrepreneur, Vassiliy Boyko. Ms. Sharoykina replies “He has problems with law-enforcement. He may wish to reabilitate himself. Give him a try”.

This piece of advice is significant in that it comes from Malofeev’s associate. Konstantin Malofeev himself was the center of a number of legal issues, among which investigations over defrauding the state-owned bank VTB of more than $220 m, and separately for vote-rigging a regional election; all of which seemed to have been absolved as of early 2014.

This piece of advice is significant in that it comes from Malofeev’s associate. Konstantin Malofeev himself was the center of a number of legal issues, among which investigations over defrauding the state-owned bank VTB of more than $220 m, and separately for vote-rigging a regional election; all of which seemed to have been absolved as of early 2014.

Ms. Sharoykina initially denied any connection between the email address identified in the leak and herself, and insisted that neither she, nor Konstantin Malofeev had any involvement with “operations in Eastern Europe”. When confronted with an email from Usovsky that spells her full name in full, she abruptly discontinued further communication.

***

Several months following the elections, in June 2015, freshly re-elected Milorad Dodik awarded Konstantin Malofeev, Leonid Reshetnikov, and Putin’s adviser and close friend of Malofeeev, Igor Shtegolev, Orders of Njegos – First Degree for contribution to the “formation of the Republika Srpska”.

In 2016, Dodik held an unconstitutional referendum for instituting a separate state holiday for RS, and has since pledged to hold a referendum for secession from Bosnia and Herzegovina in 2018; both actions in furtherance to the plan laid out in Dugin’s memorandum from October 2014. These actions have landed him on the US sanctions list. Republika Srpska’s small voice against Europe and the US, and in favor of Russia is as loud as ever before.

In Part 2 of this investigation Bellingcat and The Insider review evidence for the role of Konstantin Malofeev, Kremlin’s think-tank RISS and GRU in the failed coup attempt in Montenegro.

By Christo Grozev, Bellingcat