By Beatriz Farrugia, for DFRLab

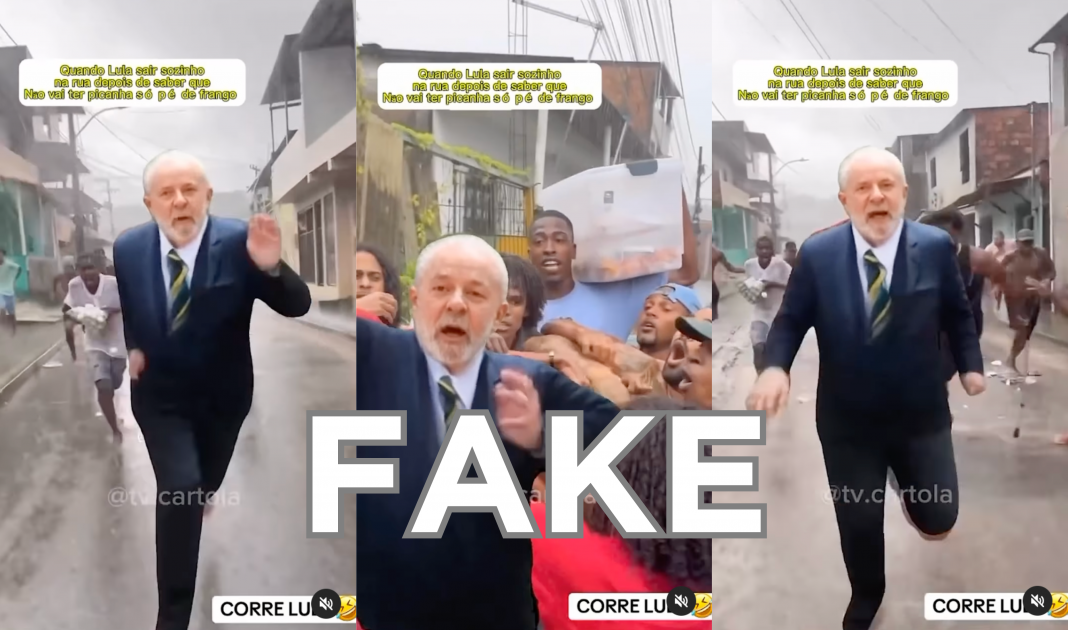

BANNER: Screencaps from a fake video featuring President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva that was shared on July 1, 2024 by Kim Kataguiri, then a pre-candidate for mayor of São Paulo. (Source: Kim Kataguiri/Instagram)

For the first time, Brazil will hold elections under electoral regulations that stipulates strict transparency rules requiring for the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) by political campaigns. The DFRLab and the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro’s NetLab UFRJ are testing various methodologies to examine the landscape of research methods to help identify electoral deepfakes during the pre-campaign period. To date, we have identified a series of challenges for open source researchers regarding data collection and consistent detection of AI-generated content on social networks and messaging applications. These illustrate the difficulties for researchers and others attempting to identify generative content during the current election cycle.

The Superior Electoral Court (TSE), responsible for organizing and monitoring the election in Brazil, announced the new regulations in February 2024, more than six months ahead of the October 6 election, when approximately 155 million Brazilians are expected to go to the polls to elect mayors and councilors for the country’s 5,568 municipalities. The deceptive use of AI is one of the primary concerns of the TSE in this election; as such, the new regulations codify rules stating that any campaign content generated or edited by AI must feature a disclaimer acknowledging the use of AI.

The new regulations grant the TSE wide latitude in terms of potential punishment for campaigns caught using AI content deceptively, particularly in the context of deepfakes or other generative content that presents falsified footage of people. According to the electoral resolution, “The use, to harm or favor candidacy, of synthetic content in audio, video format or a combination of both, which has been digitally generated or manipulated, is prohibited, even with authorization, to create, replace or alter the image or voice of a living, deceased or fictitious person (deep fake).” Potential punishments for candidates whose campaigns violate this rule including removal from ballots and disqualifying their eligibility for election.

This is the second installment from the DFRLab and NetLab UFRJ regarding AI and the October 2024 Brazilian municipal elections. In May, we examined the new regulations in detail, available in Portuguese and English.

Platform compliance

Monitoring the use of AI in the 2024 elections fundamentally depends on the technical capacity to identify and archive synthetic media for subsequent content evaluation. In August, the TSE signed a memorandum of understanding with Meta, TikTok, LinkedIn, Kwai, X, Google, and Telegram, through which the companies committed to acting quickly and in partnership with Brazilian authorities to remove disinformation content. The agreements are valid through December 31, 2024. Additionally, these companies signed the voluntary AI Election Accord, which establishes seven principle goals to set expectations for how signatories manage the risks arising from deceptive AI election content.

Under the agreement with the TSE, the platforms are notified by the Integrated Center for Combating Disinformation and Defense of Democracy (CIEDDE) of any registered complaints regarding deceptive campaign uses of AI. CIEDDE is a body made up of representatives from the TSE and six other Brazilian public institutions, including the National Telecommunications Agency (Anatel), the Federal Public Ministry (MPF), the Ministry of Justice and Public Security (MJSP), and the Federal Police (PF). Established in May 2024, the center aims to coordinate all relevant complaints in Brazilian territory and forward them to the platforms.

While these agreements establish a standard process for notifying the TSE, they do not address any standards or methodologies for AI detection or platform enforcement. The agreements only address the platforms’ general obligation to investigate complaints received by CIEDDE and to engage in content moderation if deemed warranted. For example, in its agreement with Meta, the TSE is responsible for the initial examination of complaints and subsequent platform notification of its findings. However, the agreement clarifies that receiving complaints does not oblige Meta to take any action that is not in line with existing content enforcement policies, creating scenarios in which the TSE identifies a potential violation of its AI regulations that does not necessarily lead to deplatforming or other content moderation mechanisms employed by Meta.

The agreement with Google follows a similar structure, referencing a joint agreement to act in a coordinated, quick, and effective way to combat the spread of disinformation. As announced at the end of April 2024, Google announced it would prohibit the broadcast of political advertising on its platform in Brazil beginning on May 1, claiming it did not have the technical capacity to comply with a regulatory requirement to maintain a repository of political ads. In July, NetLab UFRJ published a technical note arguing that Google’s decision would fail to prevent the publication of political ad while simultaneously making it more difficult for researchers and election monitors to identify instances campaigns deceptively using AI content.

Identifying instances of deceptive AI content

To identify potential instances of deceptive AI in the pre-campaign period, the DFRLab and NetLab UFRJ conducted joint analysis of publicly accessible campaign content on social networks, messaging applications, and websites from June 1 to August 15, 2024. Operating under the premise that deepfakes intended to spread disinformation or harm would not be openly declared as deepfakes by their producers, researchers sought to identify user discussions or reports referencing political deepfakes, given that many of the complaints ultimately received by the TSE would surface through such discussions. This points to an inherent limitation for researchers as well as the TSE: the most effective instances of deepfakes or other AI-generated content might not be recognizable as fake to the typical consumer, decreasing the likelihood of reporting. There may also be instances in which people discussing potential instances of AI recognize that the content is deceptive but don’t use relevant keywords that would assist researchers or monitoring bodies to observe these discussions. And for the TSE, there is the additional challenge that there is no guarantee that internet users who identify potential violations of the AI regulations will report them for official review. These factors add up to a high likelihood of Brazilian internet users spotting or discussing potential instances of deceptive campaign AI without further analysis or action taking place.

During the pre-campaign period, we observed election-related conversations on X, Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube via the tool Junkipedia. Simultaneously, we identified 815 official profiles for the mayoral pre-candidates of Brazilian state capitals to track potential instances campaigns circulating deceptive AI content. We then applied the Portuguese equivalents for the keywords “deepfake,” “deep fake,” and “artificial intelligence” to filter through the 58,271 threads published made by the pre-candidates between June 1 and August 15, 2024.

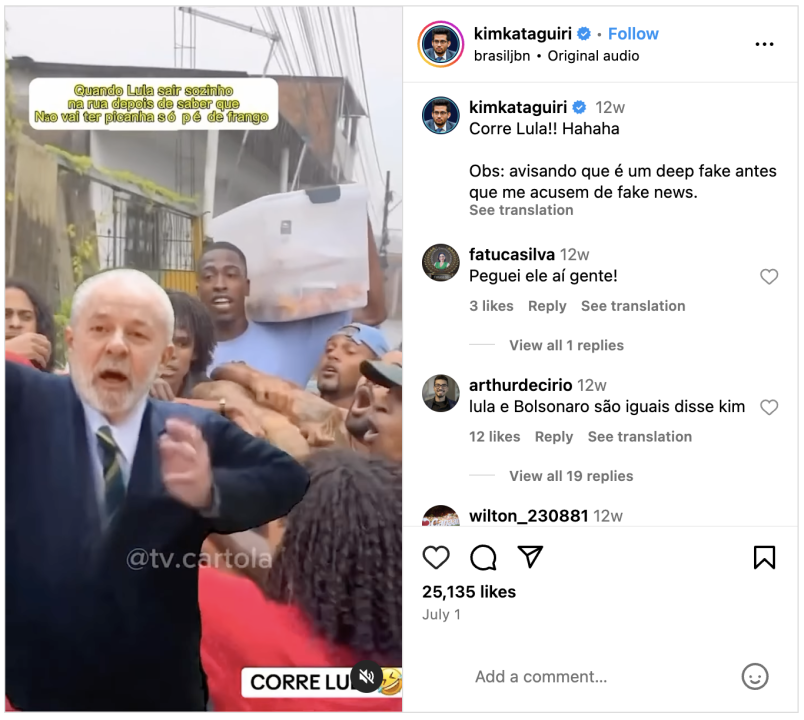

The search for the keywords “deepfake” and “deep fake” returned only one result: a video posted on July 1 to Instagram by federal deputy Kim Kataguiri, then a pre-candidate for mayor of São Paulo. The footage is obviously fake, depicting President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva running through the streets and escaping from a group of men. The video contained the text, “When Lula goes out alone on the street after knowing that there will be no steaks, just chicken feet.” In the post, Kataguiri acknowledged that the content was likely AI-generated: “Run Lula!! Hahaha Note: warning you that it is a deep fake before they accuse me of fake news.”

While the video is likely an instance of political humor, the Brazilian regulation does not distinguish between types of deepfakes, stipulating that candidates must inform the audience about any and all content created or edited by AI. In this particular instance, the candidate complied with that requirement.

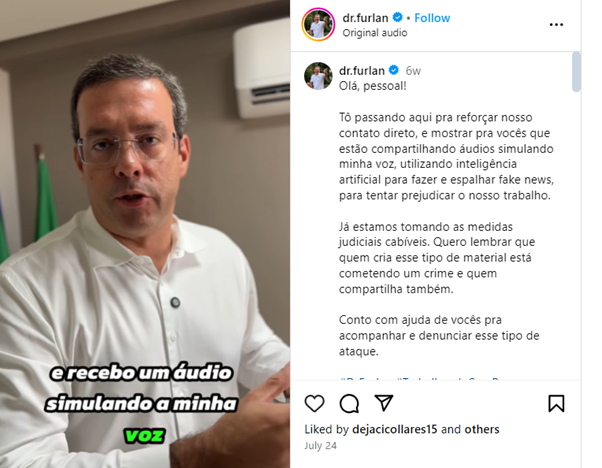

The search for the keyword “artificial intelligence” identified forty-five additional posts. Most of the posts contained either content related to proposals from pre-candidates to use AI to optimize administrative processes or news reports and discussions about the application of AI. One instance, however, referred to a potential instance of deceptive AI content. On July 24, a candidate for mayor of Macapá, Antonio Furlan, published a video on Instagram alerting his followers that he had been the victim of audio clips that impersonated his voice and were being shared intentionally to negatively affect his reputation.

“We are already taking appropriate judicial measures,” the candidate noted in his post. “I want to remind you that whoever creates this kind of material is committing a crime and whoever shares it as well. I count on your help to follow up and report this type of attack.”

Another post containing the keyword “artificial intelligence” referred to a video edited with AI to create a meme showing Brazilian Finance Minister Fernando Haddad’s face imposed on a character of the movie “Gladiator.” In the edited footage, Haddad has a conversation with another character about taxes. The video was shared on July 19 on Instagram and Facebook by Paulo Martins, a candidate for vice mayor of Curitiba, who mocked the clip. “Someone needs to stop artificial intelligence

Messaging platforms

Our analysis of public content posted to messaging platforms focused on on WhatsApp and Telegram. On WhatsApp, we identified 1,588 public groups and channels dedicated to discussing politics, comprised of 47,851 subscribers. We manually identified these communities through search engines like Google and websites that share lists of public groups. Prior to archiving in a SQLite database for analysis, we removed any instances of personal identifiable information such as phone numbers and email addresses. On Telegram, we identified 854 public groups with 76,064 subscribers. We utilized the Telegram API to collect and analyze data, exported through the Python library Telethon.

Initial searches were carried out using the Portuguese equivalents of the keywords “deepfake” or “deep fake.” On both platforms, though, the results were irrelevant to the scope of monitoring or resulted in false positives. Some messages alluded to cases of deepfakes in other countries; others erroneously reported legitimate content as deepfakes, or were discussions about the dangers of deepfakes. Ultimately, no electoral deepfakes were found in this particular dataset. We therefore conducted additional analyses on both applications to identify reports of AI use. This included searches for Portuguese keyword equivalents for phrases such as “made by AI,” “made by Artificial Intelligence,” “AI-generated,” “generated by Artificial Intelligence,” “manipulated by AI,” and “manipulated by Artificial Intelligence.” Searches for these keywords included additional Portuguese linguistic equivalents accounting for variations in grammatical gender and number. Despite the expanded search parameters, the queries resulted is no results that were relevant to the scope of monitoring.

Meta platforms and the Meta Ad Library

Another methodology tested from June to August utilized the Meta Ad Library, a repository of content promoted on the Meta platforms Facebook, Instagram, and Messenger. Our aim was to identify instances of political ads that contained deceptive AI content.

In April 2024, Meta announced that AI-generated or AI-manipulated content on its platforms would be accompanied by a content label. Enforcement has been mixed, however. During the first round of European parliamentary elections in June 2024, the DFRLab identified instances of AI-generated content circulated on Facebook by the French affiliate of the far-right coalition known as Identity and Democracy (ID). The following month, POLITICO reported on AI-generated content circulating on Meta platforms prior to the second round of France’s parliamentary elections. Additionally, Meta’s Ad Library and API do not currently contain filters for AI-generated content, leaving researchers without specific tools to identify AI content on their platforms. It remains unclear how many additional cases of AI-generated content occurred during these elections, particularly in the wake of Meta’s decision to shutter CrowdTangle, a platform analysis tool used by independent media and the research community, which has since been replaced by a content library with more limited search capabilities.

Regarding AI content in political advertising, Meta has mandated that advertisers must include synthetic content labels for political or electoral ads:

Advertisers must disclose whenever an ad about social issues, elections or politics contains a photorealistic image, video or realistic-sounding audio that was digitally created or altered to depict any of the following:

• A real person as saying or doing something they didn’t say or do

• A realistic-looking person that doesn’t exist

• A realistic-looking event that didn’t happen

•Altered footage of a real event that happened

• A realistic event that allegedly happened, but that’s not a true image, video or audio recording of the event

If you do not disclose these specified scenarios, your ad may be removed. Repeated failure to disclose may result in penalties on the account.

The rules go on to state, “In the Ad Library, the Ad details section will include information about digitally created or altered media.” At the time of writing it, however, the Meta Ad Library lacked functionality to search for ads containing these labels. As an additional challenge, users cannot flag potentially problematic content in ads published to Meta platforms for further review by the company.

Instances of deepfakes identified by Brazilian media and bloggers

Our research also tested the feasibility of using Google Alerts to monitor the publication of content on blogs and news websites that mention relevant keywords, including the Portuguese equivalents for “artificial intelligence,” “AI,” “deepfake”, “elections,” “candidate,” and “candidate.” We identified sixteen cases of deepfakes reported by press or blogs in the states of Amazonas, Rio Grande do Sul, Sergipe, São Paulo, Mato Grosso do Sul, Pernambuco, Paraná, Rio Grande do Norte and Maranhão. According to the reports, most deepfakes circulated in WhatsApp groups and were identified by the victims themselves. In nine cases, the victims took legal action to remove the content and identify those responsible for the posts.

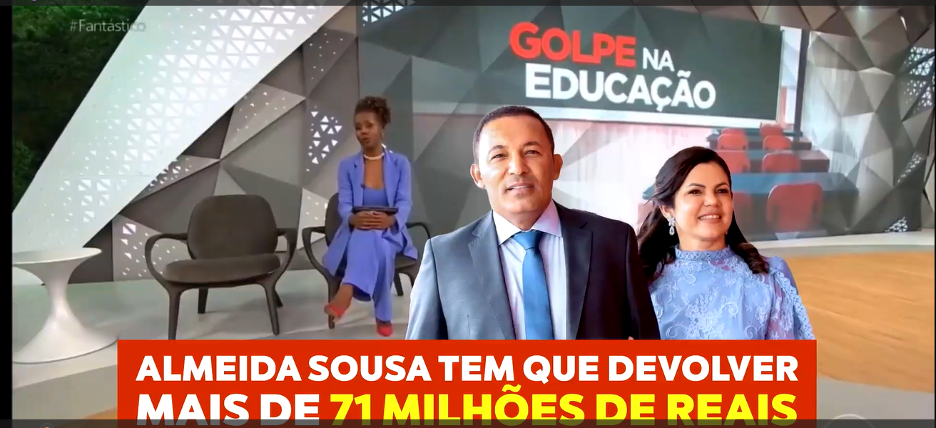

For example, on August 6, a case emerged in Igarapé do Meio, a city located in the state of Maranhão. A deepfake video accused the local government of financial fraud in the public education system, manipulating genuine footage published in January 2024 by the TV program “Fantátisco.”

The original footage referred to financial crimes committed by public authorities in the cities of Turiaçu, São Bernardo, and São José de Ribamar, all located in the state of Maranhão. The deepfake video may have been created with the intention of damaging the reputation of Almeida Sousa, mayor of Igarapé do Meio, who is supporting the candidacy of his wife, Solange Almeida.

Another case emerged on the same day in Mirassol, a city in the state of São Paulo. A video incorporated a fake voiceover impersonating President Lula. The video invited the local population to an electoral event in support of candidate Ricci Junior, despite him being from a different political party. According to Junior’s staff, the video circulated in WhatsApp groups. Mirassol Conectada, which reported on the video, also noted that the municipal electoral court established a daily fine of R$2,000 – approximately USD $368 – for anyone who continued to circulate it.

Addressing present research challenges

As demonstrated in this analysis, there are limitations in available research methodologies to monitor the proliferation of AI-generated imagery at scale. The methodologies tested showed that identifying cases of deepfakes through keyword searches is not sufficient, as instances of internet users discussing whether or not a piece of content was AI-generated often resulted in false positives or results that were out of scope.

The methodology of using Google Alerts proved to be more efficient for identifying instances of deceptive electoral AI content, but these were limited to documented cases that were already in the public domain, either covered by the press or under judicial review.

Difficulties in conducting search queries and data collection within the platforms themselves also limited the number of observable case studies. None of the examined platforms offered dedicated functionalities for identifying content with AI labels. There are also limitations regarding users’ ability to flag certain types of platform content that may contain deceptive AI, and alternative collection methods such as auto-detection of AI-manipulated content are computationally very expensive at scale. Improving the functionality of platform search tools to surface AI-generated content would be enormously beneficial for the research community, particularly during high-stakes events such as elections.

Due to these current limitations in platform search capabilities, identifying AI-generated content remains a laborious process, requiring ongoing and often manual monitoring, whether by the research community, electoral officials, or the public at large. Nonetheless, the collective capacity of internet users to identify potential instances of deceptive electoral AI is potentially enormous; this could be employed effectively in the form of tip lines to submit possible cases to independent fact-checkers. For instance, in Brazil, some fact-checkers like Agencia Lupa have WhatsApp accounts where the public can send content circulating on messaging apps and social media platforms for verification. A similar approach could be successful in tracking potential deepfakes and other forms of deceptive AI electoral content.

Identifying deceptive AI content is further compounded by the fact that AI detection tools remain in their infancy, with varying levels of accuracy that at present make them a potential source for false positives or false negatives when conducting research. Some tools, such as TrueMedia, show promise. Free and available to the public, TrueMedia uses multiple indicators for identifying the use of AI, and also incorporates manual review by professional analysts. Despite this progress, the overall risk of false positives or false positives remains high among AI detection tools, which could lead to further confusion by the public and potential exploitation by candidates who attempt to present real content as AI-generated in an attempt to avoid accountability.

Learning lessons from Brazil and beyond

Brazil’s new electoral rules are an important milestone in evaluating the enforcement and effectiveness of government AI regulations. Brazilian electoral authorities, as well as third parties such as independent media, academia and civil society, should conduct and publish further analysis to learn from this election cycle and apply that knowledge constructively to future elections. Platforms can assist multi-sector research efforts by requiring users to label AI-generated content and improve their systems’ search capabilities to surface political advertisements and campaign-related content that has been labeled as such. If necessary, the TSE should also consider updating its memoranda of understanding with platforms to mandate these labeling requirements and functionalities if voluntary measures prove insufficient.

It would also be beneficial for the TSE to take note of similar efforts in Europe and apply lessons learned from them if deemed appropriate . The European Union’s Artificial Intelligence Act and Digital Services Act (DSA), which contain provisions that explicitly relate to detecting and mitigating deceptive AI content in the run-up to elections, offer interesting learning opportunities. The AI Act requires platforms to “identify and mitigate systemic risks that may result from the disclosure of artificially generated or manipulated content, in particular, the risk of real or foreseeable negative effects on democratic processes, public debate and electoral processes, particularly through disinformation.” While the AI Act was not yet in force during the 2024 European parliamentary elections, the platforms that fall under the most stringent oversight conditions of the Digital Services Act pledged to identify, label, and sometimes remove harmful synthetic content. As previously noted, however, researchers and independent media observed multiple instances of AI-generated images lacking appropriate labeling, some of which also appeared in political advertising.

Additional EU legislation on the transparency and targeting of political advertising also addresses platforms’ targeting mechanisms, requiring them to report whether AI models influence political advertising segmentation and targeting systems. These provisions will not take full force until 2026, however, so it is too early to discern their effectiveness.

The DFRLab and NetLab UFRJ continue to monitor social networks and messaging platforms to identify potential instances of deceptive electoral AI during the Brazilian election campaign. The election takes place on October 6, 2024.

By Beatriz Farrugia, for DFRLab

This piece was published as part of a collaboration between the DFRLab and NetLab UFRJ, which published a version of this article in Portuguese. Both organizations are monitoring the use of AI tools during the 2024 Brazilian municipal elections to better understand their impact on democratic processes.