Fascism returns to the continent it once destroyed.

We easily forget how fascism works: as a bright and shining alternative to the mundane duties of everyday life, as a celebration of the obviously and totally irrational against good sense and experience. Fascism features armed forces that do not look like armed forces, indifference to the laws of war in theirapplication to people deemed inferior, the celebration of “empire” after counterproductive land grabs. Fascism means the celebration of the nude male form, the obsession with homosexuality, simultaneously criminalized and imitated. Fascism rejects liberalism and democracy as sham forms of individualism, insists on the collective will over the individual choice, and fetishizes the glorious deed. Because the deed is everything and the word is nothing, words are only there to make deeds possible, and then to make myths of them. Truth cannot exist, and so history is nothing more than a political resource. Hitler could speak of St. Paul as his enemy,Mussolini could summon the Roman emperors. Seventy years after the end of World War II, we forgot how appealing all this once was to Europeans, and indeed that only defeat in war discredited it. Today these ideas are on the rise in Russia, a country that organizes its historical politics around the Soviet victory in that war, and the Russian siren song has a strange appeal in Germany, the defeated country that was supposed to have learned from it.

The pluralist revolution in Ukraine came as a shocking defeat to Moscow, and Moscow has delivered in return an assault on European history. Even as Europeans follow with alarm or fascination the spread of Russian special forces from Crimea through Donetsk and Luhansk, Vladimir Putin’s propagandists seek to draw Europeans into an alternative reality, an account of history rather different from what most Ukrainians think, or indeed what the evidence can bear. Ukraine has never existed in history, goes the claim, or if it has, only as part of a Russian empire. Ukrainians do not exist as a people; at most they are Little Russians. But if Ukraine and Ukrainians do not exist, then neither does Europe or Europeans. If Ukraine disappears from history, then so does the site of the greatest crimes of both the Nazi and Stalinist regimes. If Ukraine has no past, then Hitler never tried to make an empire, and Stalin never exercised terror by hunger.

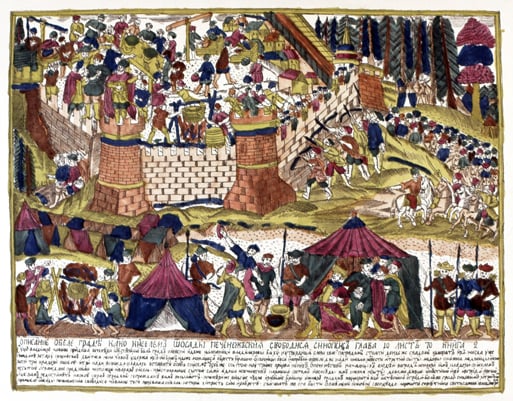

Ukraine does of course have a history. The territory of today’s Ukraine can very easily be placed within every major epoch of the European past. Kiev’s history of east Slavic statehood begins in Kiev a millennium ago. Its encounter with Moscow came after centuries of rule from places like Vilnius and Warsaw, and the incorporation of Ukrainian lands into the Soviet Union came only after military and political struggles convinced the Bolsheviks themselves that Ukraine had to be treated as a distinct political unit. After Kiev was occupied a dozen times, the Red Army was victorious, and a Soviet Ukraine was established as part of the new Soviet Union in 1922.

Precisely because the Ukrainians were difficult to suppress, and precisely because Soviet Ukraine was a western borderland of the USSR, the question of its European identity was central from the beginning of Soviet history. Within Soviet policy was an ambiguity about Europe: Soviet modernization was to repeat European capitalist modernity, but only in order to surpass it. Europe might be either progressive or regressive in this scheme, depending on the moment, the perspective, and the mood of the leader. In the 1920s, Soviet policy favored the development of a Ukrainian intellectual and political class, on the assumption that enlightened Ukrainians would align themselves with the Soviet future. In the 1930s, Soviet policy sought to modernize the Soviet countryside by collectivizing the land and transforming the peasants into employees of the state. This brought declining yields as well as massive resistance from a Ukrainian peasantry who believed in private property.

Joseph Stalin transformed these failures into a political victory by blaming them on Ukrainian nationalists and their foreign supporters. He continued requisitions of grain in Ukraine, in the full knowledge that he was starving millions of human beings, and crushed the new Ukrainian intelligentsia. More than three million people were starved in Soviet Ukraine. The consequence was a new Soviet order of intimidation, where Europe was presented only as a threat. Stalin claimed, absurdly but effectively, that Ukrainians were deliberately starving themselves on orders from Warsaw. Later, Soviet propaganda maintained that anyone who mentioned the famine must be an agent of Nazi Germany.

Thus began the politics of fascism and anti-fascism, where Moscow was the defender of all that was good, and its critics were fascists. This very effective pose, of course, did not preclude an actual Soviet alliance with the actual Nazis in 1939. Given today’s return of Russian propaganda to anti-fascism, this is an important point to remember: The whole grand moral Manichaeism was meant to serve the state, and as such did not limit it in any way. The embrace of anti-fascism as a rhetorical strategy is quite different from opposing actual fascists.

Ukraine was at the center of the policy that Stalin called “internal colonization,” the exploitation of peasants within the Soviet Union rather than distant colonial peoples; it was also at the center of Hitler’s plans for an external colonization. The Nazi Lebensraum was, above all, Ukraine. Its fertile soil was to be cleared of Soviet power and exploited for Germany. The plan was to continue the use of Stalin’s collective farms, but to divert the food from east to west. Along the way German planners expected that some 30 million inhabitants of the Soviet Union would starve to death. In this style of thinking, Ukrainians were of course subhumans, incapable of normal political life. No European country was subject to such intense colonization as Ukraine, and no European country suffered more: It was the deadliest place on Earth between 1933 and 1945.

Although Hitler’s main war aim was the destruction of the Soviet Union, he found himself needing an alliance with the Soviet Union to begin armed conflict. In 1939, after it became clear that Poland would fight, Hitler recruited Stalin for a double invasion. Stalin had been hoping for years for such an invitation. Soviet policy had been aiming at the destruction of Poland for a long time already. Moreover, Stalin thought that an alliance with Hitler, in other words cooperation with the European far right, was the key to destroying Europe. A German-Soviet alliance would turn Germany, he expected, against its western neighbors and lead to the weakening or even the destruction of European capitalism. This is not so different from a certain calculation made by Putin today.

The result of the cooperative German-Soviet invasion was the defeat of Poland and the destruction of the Polish state, but also an important development in Ukrainian nationalism. In the 1930s, there had been no Ukrainian national movement in the Soviet Union, only an underground terrorist movement in Poland known as the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN). It was little more than an irritant in normal times, but with war, its importance grew. The OUN opposed both Polish and Soviet rule of what it saw as Ukrainian territories and thus regarded a German invasion of the east as the only way that a Ukrainian state-building process could begin. Thus the OUN supported Germany in its invasion of Poland in 1939 and would do so again in 1941, when Hitler betrayed Stalin and invaded the USSR. Meanwhile, Ukrainian left-wing revolutionaries, who had been quite numerous before the war, often shifted to the radical right after experience with Soviet rule. The Soviets assassinated the leader of the OUN, which brought a struggle for power between factions led by Stepan Bandera and Andrii Melnyk.

Ukrainian nationalists tried political collaboration with Germany in 1941 and failed. Hundreds of Ukrainian nationalists joined in the German invasion of the USSR as scouts and translators, and some of them helped the Germans organize pogroms of Jews. Ukrainian nationalist politicians tried to collect their debt by declaring an independent Ukraine in June 1941. Hitler was completely uninterested in such a prospect. Much of the Ukrainian nationalist leadership was killed or incarcerated. Bandera himself spent most of the rest of the war in the prison camp at Sachsenhausen.

As the war continued, many Ukrainian nationalists prepared themselves for a moment of revolt when Soviet power replaced German. They saw the USSR as the main enemy, partly for ideological reasons, but mainly because it was winning the war. In the province of Volhynia, nationalists established a Ukrainian Insurgent Army whose task was to somehow defeat the Soviets after the Soviets had defeated the Germans. Along the way it undertook a massive and murderous ethnic-cleansing of Poles in 1943, killing at the same time a number of Jews who had been hiding with Poles. This was not in any sense collaboration with the Germans, but rather the murderous part of what its leaders saw as a national revolution. The Ukrainian nationalists went on to fight the Soviets in a horrifying partisan war, in which the most brutal tactics were used by both sides.

The political collaboration and the uprising of Ukrainian nationalists were, all in all, a minor element in the history of the German occupation. As a result of the war, something like six million people were killed on the territory of today’s Ukraine, including about 1.5 million Jews. Throughout occupied Soviet Ukraine, local people collaborated with the Germans, as they did throughout the occupied Soviet Union and indeed throughout occupied Europe. Thousands of Russians collaborated with the German occupation, and showed no more and no less inclination to do so than Ukrainians.

The real contrast is not between Ukrainians and other Soviet peoples, but between Soviet peoples and Western Europeans. In general, Soviet peoples were killed in far higher numbers in and out of uniform by the Germans than were Western Europeans. Far, far more people in Ukraine were killed by the Germans than collaborated with them, something which is not true of any occupied country in continental Western Europe. For that matter, far, far more people from Ukraine fought against the Germans than on the side of the Germans, which is again something that is not true of any continental Western European country. The vast majority of Ukrainians who fought in the war did so in the uniform of the Red Army. More Ukrainians were killed fighting the Wehrmacht than American, British, and French soldiers—combined.

Russian propaganda today falsely insists that the Red Army was a Russian army. And if the Red Army is seen as a Russian army, then Ukrainians must have been the enemy. This line of thinking was invented by Stalin himself at the end of the war. After Ukrainians were praised during the war for their suffering and resistance, they were slandered and purged after the war for their disloyalty. As late Stalinism merged with a certain kind of Russian nationalism, Stalin’s idea of the Great Patriotic War had two purposes: It started the action in 1941 rather than 1939 so that the Nazi-Soviet alliance was forgotten, and it placed Russia at the center of events even though Ukraine was much more at the center of the war, and Jews were its chief victims.

But it is the propaganda of the 1970s much more than theexperience of the war that counts in the memory politics of today. The present generation of Russian politicians are children of the 1970s and thus of Leonid Brezhnev’s cult of the war. Under Brezh-nev, the war became more simply Russian, without Ukrainians and Jews. The Jews suffered more than any other Soviet people, but the Holocaust was beyond the mainstream Soviet history. Instead it was emphasized in Soviet propaganda directed to the West, in which the suffering of Jews was blamed on Ukrainian and other nationalists—people who lived on the territories Stalin had conquered during the war as Hitler’s ally in 1939 and people who had resisted Soviet power when it returned in 1945. This is a tradition to which Russian propagandists have returned in today’s Ukrainian crisis: total indifference to the Holocaust except as apolitical resource useful in manipulating people in the West.

The greatest threat to a distinct Ukrainian identity came perhaps from the Brezhnev period. Rather than subordinating Ukraine by hunger or blaming Ukrainians for war, the Brezhnev policy was to absorb the Ukrainian educated classes into the Soviet humanist and technical intelligentsias. As a result, the Ukrainian language was driven from schools, and especially from higher education. Ukrainians who insisted on human rights were still punished in prison or in the hideous psychiatric hospitals. In this atmosphere, Ukrainian patriots, and even Ukrainian nationalists, embraced a civic understanding of Ukrainian identity, downplaying older arguments about ancestry and history in favor of a more pragmatic approach to common political interests.

On December 1991, more than 90 percent of the inhabitants of Soviet Ukraine voted for independence (including a majority in all regions of Ukraine). Russia and Ukraine then went their separate ways. Privatization and lawlessness led to oligarchy in both countries. In Russia, the oligarchs were subdued by a centralized state, whereas in Ukraine, they generated their own strange sort of pluralism. Until very recently, all presidents in Ukraine oscillated between east and west in their foreign policy and among oligarchic clans in their domestic loyalties.

What was unusual about Viktor Yanukovych, elected in 2010, is that he tried to end all pluralism. In domestic policy, he generated a fake democracy, in which his favored opponent was thefar-right party Svoboda. In so doing, he created a situation in which he could win elections and in which he could tell foreign observers that he was at least better than the nationalist alternative. In foreign policy, he found himself pushed toward the Russia of Putin, not so much because he desired this, but because his kleptocratic corruption was so extreme that serious economic cooperation with the European Union would have meant a legal challenge to his economic power. Yanukovych seems to have stolen so much from state coffers that the state itself was on the point of bankruptcy in 2013, which also made him vulnerable to Russia. Moscow was willing to overlook Yanukovych’s own practices and lend the money needed to make urgent payments—at a political price.

By 2013, oscillating between Russia and the West was no longer possible. By then, Moscow had ceased to represent simply a Russian state with more or less calculable interests, but rather a much grander vision of Eurasian integration. The Eurasian project had two parts: the creation of a free trade bloc of Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, and Kazakhstan, and the destruction of the European Union through the support of the European far right. Putin’s goal was and remains eminently simple. His regime depends upon the sale of hydrocarbons that are piped to Europe. A united Europe could generate an actual policy of energy independence, under the pressures of Russian unpredictability or global warming—or both. But a disintegrated Europe would remain dependent on Russian hydrocarbons.

Just as soon as these vaulting ambitions were formulated, the proud Eurasian posture crashed upon the reality of Ukrainian society. In late 2013 and early 2014, the attempt to bring Ukraine within the Eurasian orbit produced exactly the opposite result. First, Russia publicly dissuaded Yanukovych from signing a trade agreement with the European Union. This brought protests in Ukraine. Then Russia offered a large loan and favorable gas prices in exchange for crushing the protests. Harsh Russian-style laws introduced in January transformed the protests into a mass movement. Millions of people who had joined in peaceful protests were suddenly transformed into criminals and some of them began to defend themselves against the police. Finally, Russia made clear that Yanukovych had to rid Kiev of protesters in order to receive its money. Then followed the sniper massacre of February, which gave the revolutionaries a clear moral and political victory, and forced Yanukovych to flee to Russia. The attempt to create a pro-Russian dictatorship in Ukraine led to the opposite outcome: the return of parliamentary rule, the announcement of presidential elections, and a foreign policy oriented toward Europe.

This made the revolution in Ukraine not only a disaster for Russian foreign policy, but a challenge to Putin’s regime at home. The weakness of Putin’s policy is that it cannot account for the actions of free human beings who choose to organize themselves in response to unpredictable historical events. Russian propaganda presented the Ukrainian revolution as a Nazi coup and blamed Europeans for supporting these supposed Nazis. This version, although ridiculous, was much more comfortable in Putin’s mental world, since it removed from view the debacle of his own foreign policy in Ukraine and replaced spontaneous action by Ukrainians with foreign conspiracies.

The creeping Russian invasions of Crimea, Donetsk, and Luhansk are a frontal challenge to the European security order as well as to the Ukrainian state. They have nothing to do with popular will or the protection of rights: Even Crimean opinion polls never registered a majority preference for joining Russia, and speakers of Russian in Ukraine are far freer than speakers of Russian in Russia. The Russian annexation was carried out, tellingly, with the help of Putin’s extremist allies throughout Europe. No reputable organization would observe the electoral farce by which 97 percent of Crimeans supposedly voted to be annexed. But a ragtag delegation of right-wing populists, neo-Nazis, and members of the German party Die Linke (the Left Party) were happy to come and endorse the results. The Germans who traveled to Crimea included four members of Die Linke and one member of Neue Rechte (New Right). This is a telling combination.

Die Linke operates within the virtual reality created by Russian propaganda, in which the task of the European left (or rather “left”) is to criticize the Ukrainian right—but not the European right, and certainly not the Russian right. This is also an American phenomenon, visible for example in the otherwise surprising accord on the nature of the Ukrainian revolution and the reasonableness of the Russian counterrevolution expressed in Lyndon Larouche’s Executive Intelligence Review, the Ron Paul Institute for Peace and Prosperity, and The Nation.

Of course, there is some basis for concern about the far right in Ukraine. Svoboda, which was Yanukovych’s house opposition, now holds three of 20 ministerial portfolios in the current government. This overstates its electoral support, which is down to about 2 percent. Some of the people who fought the police during the revolution, although by no means a majority, were from a new group called Right Sector, some of whose members are radical nationalists. Its presidential candidate is polling at below 1 percent, and the group itself has something like 300 members. There is support for the far right in Ukraine, although less than in most members of the European Union.

A revolutionary situation always favors extremists, and watchfulness is certainly in order. It is quite striking, however, that Kiev returned to order immediately after the revolution and that the new government has taken an almost unbelievably calm stance in the face of Russian invasion. There are very real political differences of opinion in Ukraine today, but violence occurs in areas that are under the control of pro-Russian separatists. The only scenario in which Ukrainian extremists actually come to the fore is one in which Russia actually tries to invade the rest of the country. If presidential elections proceed as planned in May, then the unpopularity and weakness of the Ukrainian far right will be revealed. This is one of the reasons that Moscow opposes those elections.

People who criticize only the Ukrainian right often fail to notice two very important things. The first is that the revolution in Ukraine came from the left. It was a mass movement of the kind Europeans and Americans now know only from the history books. Its enemy was an authoritarian kleptocrat, and its central program was social justice and the rule of law. It was initiated by a journalist of Afghan background, its first two mortal casualties were an Armenian and a Belarusian, and it was supported by the Muslim Crimean Tatar community as well as many Ukrainian Jews. A Jewish Red Army veteran was among those killed in the sniper massacre. Multiple Israel Defense Forces veterans fought for freedom in Ukraine.

The Maidan functioned in two languages simultaneously, Ukrainian and Russian, because Kiev is a bilingual city, Ukraine is a bilingual country, and Ukrainians are bilingual people. Indeed, the motor of the revolution was the Russian-speaking middle class of Kiev. The current government, whatever its shortcomings, is un-self-consciouslymultiethnic and multilingual. In fact, Ukraine is now the site of the largest and most important free media in the Russian language, since important media in Ukraine appears in Russian and since freedom of speech prevails. Putin’s idea of defending Russian speakers in Ukraine is absurd on many levels, but one of them is this: People can say what they like in Russian in Ukraine, but they cannot do so in Russia itself. Separatists in the Ukrainian east, who, according to a series of opinion polls, represent a minority of the population, are protesting for the right to join a country where protest is illegal. They are working to stop elections in which the legitimate interests of Ukrainians in the east can be voiced. If these regions join Russia, their inhabitants can forget about casting meaningful votes in the future.

This is the second thing that goes unnoticed: The authoritarian right in Russia is infinitely more dangerous than the authoritarian right in Ukraine. It is in power, for one thing. It has no meaningful rivals, for another. It does not have to accommodate itself to domestic elections or international expectations, for a third. And it is now pursuing a foreign policy that is based openly upon the ethnicization of the world. It does not matter who an individual is according to law or his own preferences: The fact that he speaks Russian makes him a Volksgenosse requiring Russian protection, which is to say invasion. The Russian parliament granted Putin the authority to invade the entirety of Ukraine and to transform its social and political structure, which is an extraordinarily radical goal. The Russian parliament also sent a missive to the Polish foreign ministry proposing a partition of Ukraine. On popular Russian television, Jews are blamed for the Holocaust; in the major newspaper Izvestiia, Hitler is rehabilitated as a reasonable statesman responding to unfair Western pressure; on May Day, Russian neo-Nazis march.

All of this is consistent with the fundamental ideological premise of Eurasia. Whereas European integration begins from the premise that National Socialism and Stalinism were negative examples, Eurasian integration begins from the more jaded and postmodern premise that history is a grab bag of useful ideas. Whereas European integration presumes liberal democracy, Eurasian ideology explicitly rejects it. The main Eurasian ideologist, Alexander Dugin, who once called for a fascism “as red as our blood,” receives more attention now than ever before. His three basic political ideas—the need to colonize Ukraine, the decadence of the European Union, and the desirability of an alternative Eurasian project from Lisbon to Vladivostok—are now all officially enunciated, in less wild forms than his to be sure, as Russian foreign policy. Dugin now provides radical advice to separatist leaders in eastern Ukraine.

Putin now presents himself as the leader of the far right in Europe, and the leaders of Europe’s right-wing parties pledge their allegiance. There is an obvious contradiction here: Russian propaganda insists to Westerners that the problem with Ukraine is that its government is too far to the right, even as Russiabuilds a coalition with the European far right. Extremist, populist, and neo-Nazi party members went to Crimea and praised the electoral farce as a model for Europe. As Anton Shekhovtsov, a researcher of the European far right, has pointed out, the leader of the Bulgarian extreme right launched his party’s campaign for the European parliament in Moscow. The Italian Fronte Nazionale praises Putin for his “courageous position against the powerful gay lobby.” The neo-Nazis of the Greek Golden Dawn see Russia as Ukraine’s defender against “the ravens of international usury.” Heinz-Christian Strache of the Austrian FPÖ chimes in, surreally, that Putin is a “pure democrat.” Even Nigel Farage, the leader of the U.K. Independence Party, recently shared Putin’s propaganda on Ukraine with millions of British viewers in a televised debate, claiming absurdly that the European Union has “blood on its hands” in Ukraine.

Presidential elections in Ukraine are to be held on May 25, which by no coincidence is also the last day of elections to the European parliament. A vote for Strache in Austria or Le Pen in France or even Farage in Britain is now a vote for Putin, and a defeat for Europe is a victory for Eurasia. This is the simple objective reality: A united Europe can and most likely will respond adequately to an aggressive Russian petro-state with a common energy policy, whereas a collection of quarrelling nation-states will not. Of course, the return to the nation-state is a populist fantasy, so integration will continue in one form or another; all that can be decided is the form. Politicians and intellectuals used to say that there was no alternative to the European project, but now there is—Eurasia.

Ukraine has no history without Europe, but Europe also has no history without Ukraine. Ukraine has no future without Europe, but Europe also has no future without Ukraine. Throughout the centuries, the history of Ukraine has revealed the turning points in the history of Europe. This seems still to be true today. Of course, which way things will turn still depends, at least for a little while, on the Europeans.

Timothy Snyder is Housum Professor of History at Yale University and the author of Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin. With Leon Wieseltier, he has planned a congress of international and Ukrainian intellectuals to meet May 16 to 19 in Kiev under the heading Ukraine: Thinking Together. This essay is a revision of an earlier article that appeared in Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung.

Author: Timothy Snyder

Original: New Republic