By Kseniya Kirillova, for CEPA

The complications of the Russia-China axis are deeper than they look, and probably involve a future of Kremlin kowtowing.

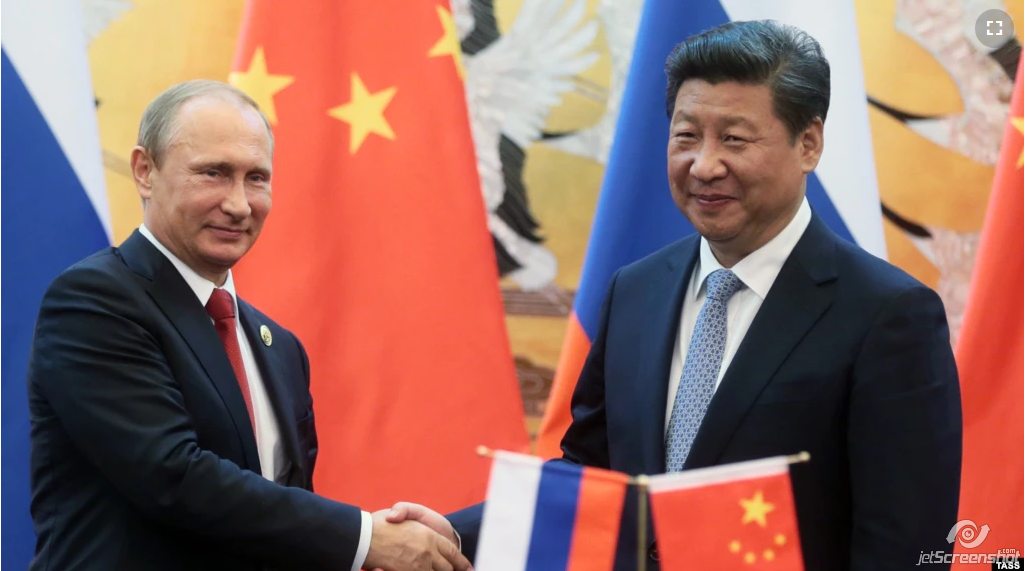

Russia and China are locked into an increasingly close embrace. That is partly because the two regimes share an ambition to torpedo the US-created global rules-based order, and its dominant currency — the dollar. Trade between the two soared by almost 30% in the first quarter of the year, fueled by significant shipments of coal to China, amid mutual expressions of affection and pledges of increasing strategic cooperation.

The sight of Russian and Chinese nuclear-capable bombers jointly patrolling the Sea of Japan on May 24 was designed to underline the message that these large dictatorships are not to be provoked.

But is that message much more than posturing? It serves Russia’s interests to suggest it has a big, nasty friend willing to help on every level; and yet the truth is that Chinese policy will never be dictated by sentiment. Its own interests come first.

In December, China’s Ambassador to Russia, Zhang Hanhui, said that countries “should continue to deepen strategic cooperation back-to-back,” including confronting the US and the West. At the same time, sinologists note that after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, China has supported Russian propaganda narratives for its domestic audience but has economically avoided anything that would trigger a direct fight with the US.

Una Alexandra Berzina-Cherenkova, head of the China Studies Center at Riga Stradins University, notes that Chinese leader Xi Jinping is using Russian narratives in his election campaign to counter the “global instability” allegedly caused by the US with a “more honest” and stable Chinese system. Marina Rudyak, a professor of sinology at the University of Heidelberg, emphasizes that while maintaining anti-Western rhetoric in its coverage of the war, Chinese propaganda nevertheless avoids describing Russia as right. Both experts agree that China is being cautious in its support for the Kremlin in order to maintain its freedom of maneuver.

Nevertheless, China has provided practical assistance to Russia in recent years. According to Russian opposition media, “in 2014-2015, the Chinese gave Russia loans to refinance company debts of more than $30bn,” and built a so-called energy bridge to Crimea. Now Russia is counting on China’s help in deepening the silt-filled Volga-Caspian Canal.

The Kremlin is also actively borrowing from Chinese experience in its domestic policy. In recent years, Russian cooperation with China in information-communications technology has increased sharply. As early as 2015, the Russian Ministry of Communications and Mass Media published a report on the joint meeting of a Russian-Chinese Commission on communications and information technology.

In June 2019, the “Joint Declaration of the Russian Federation and the Peoples Republic of China on the development of a comprehensive, strategic partnership entering a new era.” appeared on the Russian President’s website. The document calls for broadening collaboration in the field of security and consolidated the agreement “to jointly promote the principle of management of the information-telecommunications network, the Internet.” Russian cybersecurity experts have repeatedly noted that strengthening censorship and digital control is becoming one of the top priorities of the Russian authorities, and it is obvious that the Kremlin is interested in borrowing Chinese expertise in this area.

On May 23, the Current Time TV channel published information that Russia is creating so-called “denazification courses” – political schools “for the re-education of Ukrainians” that use physical violence and moral pressure. According to the human rights activist, director of the Institute for Strategic Studies and Security, Pavel Lisyansky, we can see a clear parallel with Chinese “schools” for the political re-education of the Uyghurs.

In return, China is very interested in cheap supplies of natural resources. Quite apart from rising coal imports, it is strongly focused on oil and gas from Russia, especially now that Europe is seeking to wean itself off Russian supplies. That has made Russian produce cheaper. According to Reuters, China is quietly ramping up purchases of oil from Russia at bargain prices. China’s seaborne Russian oil imports will jump to a near-record 1.1 million barrels per day (bpd) in May, up from 750,000 bpd in the first quarter, according to an estimate by Vortexa Analytics.

China is also seeking to take advantage of the situation by replenishing its strategic crude stockpiles. Some sources report that parallel negotiations are underway to expand Russian gas supplies to China at a serious discount.

Another important initiative of China and Russia is the idea of expanding the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) grouping and the China-led Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) with the possible creation of a common bank and an alternative currency as a mechanism to avoid sanctions, and put itself beyond the reach of US-led sanctions.

On May 19, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi at the online meeting of the Foreign Ministers of the BRICS member countries proposed expanding the group to include new members. Pro-Kremlin experts, in turn, are already expressing hopes that a Russian victory in Ukraine will lead to a “radical change in the world order”, and that BRICS could then maintain this new world order.

It may be that Russia will try to include some Middle Eastern countries in the SCO, for example, Saudi Arabia. American media reports suggest that U.S.-Saudi relations reached a breaking point over disagreements regarding oil production levels (with the Saudis refusing to raise output and so drive down prices), security concerns, and the invasion of Ukraine. Experts of the Russian International Affairs Council also noted this trend and have called for the expansion of Russian-Saudi relations.

However, these may be the limits of Russo-Chinese cooperation. First, China is not interested in aggravating the confrontation with the United States on behalf of another country, even as it tries to squeeze the maximum benefit from of the confrontation between Russia and the West. Secondly, in the long run, Russia’s worsening weakness actually helps it by increasing the Kremlin’s dependence (Russia’s GDP is one-tenth of China’s and its population is in serious decline.)

This dependence is already acknowledged by independent Russian experts. In particular, Vasily Kashin, an orientalist, and director of the Center for Comprehensive European and International Studies at the Higher School of Economics noted in his interview with Novaya Gazeta that about $130 billion of Russia’s gold and foreign exchange reserves are currently in yuan assets.

China’s share of Russian foreign trade has been growing for several years, and this or next year China will become its main trading partner. “Further on, Russia’s dependence on trade with China will begin to grow at a gigantic pace . . . a complete reorientation to China, I think, will happen within a year or two,” Kashin said.

Third, at the policy level, China is in no hurry to recognize the annexation of Crimea; China has always made a virtue of strict adherence to the principle of territorial integrity. There are also contradictions between various members of the SCO and BRICS (India, for example, sees China as a likely future adversary.) Moreover, quite serious competition may arise between Russia and China in several areas. One such potential zone is their level of influence in Central Asia. Back in 2019, Russian media admitted that the country is losing ground in Central Asia and the Caucasus. In their own words, the significance of China as a trade partner and investment source in the region is growing.

In addition, China may not share Russia’s ambitions to create its own economic bloc independent of both the West and China. The Russians do not conceal that with the creation of such a group they would want to strengthen the anti-Western inclinations of their potential allies, playing on their colonial past. However, any rise of Russia in Asia or the Pacific runs counter to China’s interests, which could create problems in cooperation between the two countries.

By Kseniya Kirillova, for CEPA

Kseniya Kirillova is an analyst focused on Russian society, mentality, propaganda, and foreign policy. The author of numerous articles for the Jamestown Foundation, she has also written for the Atlantic Council, Stratfor, and others.

Europe’s Edge is an online journal covering crucial topics in the transatlantic policy debate. All opinions are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the position or views of the institutions they represent or the Center for European Policy Analysis.