By Paula Chertok

Hardly a day goes by without someone from the Kremlin accusing the West of anti-Russia “frenzy,” “hysteria” or “Russophobia.” Whether the subject is the poisoning of a spy in Salisbury, a chemical weapons attack in Douma, Syria, hacking Ukraine’s electrical grid or interfering in the U.S. election for Donald Trump, Russia’s defense invariably includes indignant cries of anti-Russia sentiment. Today, Russophobia has become an end in itself.

The Kremlin’s propaganda playbook includes an array of deflection, distraction and disinformation techniques that I have examined previously. Although Russophobia, calling people Russophobic and Russophobes, seems a juvenile argumentative trope, it has taken on such a prominent position in today’s Russian propaganda machine, it’s worth fleshing out how the tactic works.

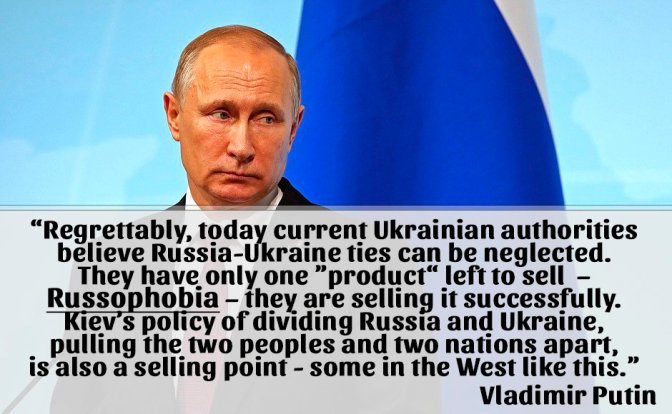

Russophobia works on Russian audiences to create a sense that the Russian people are under siege by a hostile West, afraid of Russia’s growing strength under Putin. Russia is the “victim,” the narrative goes, of an aggressive Russophobia campaign led by the US and it allies who must do everything possible to hold Russia back and keep her down. This narrative plays well to a population traumatized by poor history and poor leadership and dominated by Kremlin-run TV using the language and imagery of Cold War.

Russophobia works on Russian audiences to create a sense that the Russian people are under siege by a hostile West, afraid of Russia’s growing strength under Putin. Russia is the “victim,” the narrative goes, of an aggressive Russophobia campaign led by the US and it allies who must do everything possible to hold Russia back and keep her down. This narrative plays well to a population traumatized by poor history and poor leadership and dominated by Kremlin-run TV using the language and imagery of Cold War.

For Western audiences, looking to history reveals a certain irony in Russophobia becoming today’s Russian propaganda go-to line. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, most people in the West rejoiced along with the Russian people. The Kremlin likes to say that the West gloated in victory over its Cold War adversary. And some politicians surely promoted that view. But, for the average person, the dissolution of the USSR was seen as a victory for Western values, of freedom, human rights and self-determination over totalitarianism and repression. We saw people finally liberated from the dual yoke of dictatorship and communism, ideologies that seemingly vanished overnight. Those ideologies were the enemy, never the people. No longer communist, Russia was no longer ‘the bad guy.’ Capitalism, economic freedoms and democratic values would now unite all the former Soviet states with the West, as Russia was welcomed back into the fold.

Welcoming Russia into the international community of nations was surely anything but Russophobia. Indeed, it was the opposite. Our full-throated embrace of Russia and Russians led to opening our doors, our hearts and our banks to Russia and closing the door on our not particularly proud past – ours and Russia’s. The vocabulary of subversion, deception, and espionage were part of a discourse we had put away with blacklists, McCarthyism and the Cold War. Bringing it out in 2016 was seen as too ridiculous for fiction, and surely too absurd to reflect reality.

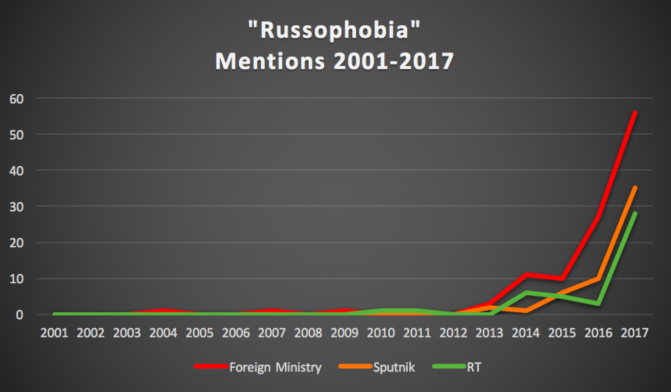

The early knee-jerk reaction to even the idea that Russia may be attacking our democracy is decidedly the opposite of anti-Russia “Russophobia” – not necessarily Russophilia, but let’s call it anti-Russophobia. For better or worse, anti-Russophobia embodies our cultural embrace of post-Soviet Russia as well as our cultural rejection of our collective past, powerful in our collective consciousness to this day. This made sense because the condition for past Russophobia – communism – had disappeared. But that just made Russian propagandists cry Russophobia louder and more often, as evidenced in the dramatic spike in usage in the last few years, coinciding with a spike in Russian aggression.

Given the reality of cultural anti-Russophobia, using the Russophobia card, and its concomitant opening of past wounds, was a clever misdirection, and surely helped create the early conditions for a disarmed public. This may explain why so many people dismissed and disbelieved Russia’s attack on the 2016 election, even though much of it was in plain sight. Granted, being under a rapid-fire information warfare assault was itself disarming, something we’ll be learning about for years to come. But anti-Russophobia sentiment – not wanting to see Russia as responsible for a manipulative attack on one of our fundamental rights – was so strong, on the left and the right (for differing reasons), the mere suggestion of Russian interference was not only quickly rejected, but itself became a sign of digging up shameful McCarthyist ghosts in a closet we thought ought to stay closed, in the past and buried. This surely helped Russia’s attack succeed.

Unlike Russians, Americans have the luxury to criticize our government, discover our history, dig up unpleasant truths, and make public our government’s failures. Ours is a far from perfect system, but the ability to feel shame for our mistakes is inextricably tied to our ability to discover them, to hold our leaders accountable, publicly, without fear of reprisals. Those deeply American values aren’t possible in Russia under Putin. While paying lip service to them at home, Russia plays on our values and relies on pushing our buttons of shame, easily pushed precisely because we have the right to call out hypocrisy on civil rights and free speech, McCarthyism, and the like. And we do so proudly, not with fear or intimidation.

Thanks to being both blessed and cursed with the good fortune not to really comprehend authoritarianism, Americans watched Russians invade our lives, our institutions, and our politics and couldn’t really wrap our heads around what was happening. And we did next to nothing.

Those of us who have been following Russia’s descent into illiberalism and kleptocracy in recent years recognized that the Kremlin was exploiting our anti-Russophobia sentiment both to divide the West and to unite Russians.

Today on an NPR (National Public Radio) broadcast, this anti-Russophobic sentiment was expressed starkly and clearly. Host Scott Simon was interviewing Bill Browder, an outspoken critic of the Putin regime and its worldwide reach. Browder retold the shocking story of the Bitkovs, a Russian family that fled Russia to Guatemala after a falling out with the Kremlin, yet Russia was still able to reach them and wreak havoc on their young family.

BROWDER: The Russian government tracked them down in Guatemala and then got a U.N. agency that’s paid for by the United States to fight corruption and impunity in Guatemala – and the Russian government got that agency to prosecute this family for passport violations and sentenced the mother – the father to 19 years in prison, the mother and daughter to 14 years in prison. And then the Russians tried to take the infant son back to an orphanage in Russia.

It’s the most remarkable story of evil coming out of Russia that I’ve seen in a long time. And what it shows is that they’re not just messing with the election in the United States or doping in the Olympics. But they’ve got their tentacles into just about everything everywhere. This is one story that shows that.

After hearing this remarkable and shocking story from Browder, Simon said:

SIMON: I have to ask you, Mr. Browder, there are plenty of people – and we hear from them – who are skeptical about Russia being seen at the center of so many allegations. And they say the U.S. and the West are just crawling back into a destructive Cold War mentality. How do you answer that? [Emphasis Added]

Browder had just told NPR a truly horrific story of a family torn apart by a menacing Russian regime, that went to extraordinary lengths – half way around the world to Guatemala – to track them down. Yet Simon, expressing a sentiment shared by many Americans, felt the need to be skeptical about the story, framing it as one of “so many allegations” against Russia, saying he hears from “plenty of people…who are skeptical about Russia being seen at the center of.” This anti-Russophobia sentiment is so strong among those who hold it, it even defies logic. Logically, more allegations and more evidence make a case stronger; yet here, the more allegations against Russia, the more people refuse to believe Russia is to blame for any of it. In other words, because of the cultural sentiment against blaming Russia, more news about Russia’s malign actions are dismissed as part of a pattern of blaming Russia, the victim of quite literally, piling on.

I’m sure that Americans’ naivete as well as good fortune, never having experienced life under dictatorship, contribute to this sentiment. We simply can’t comprehend acts of such menacing depravity on ordinary people by Russian authorities. But we also don’t want to believe that non-communist Russia could really be all that bad. For many, it simply goes against a deeply ingrained cultural ANTI-Russophobia. We resist believing Russia is a bad actor because that perception is tied to a sensitive history of shame we do not wish to repeat. So we choose to dismiss the bad news about Russia’s wrongdoing as Russophobia.

Russia understands this psychology and our history well, and exploits it every day, pushing the Russophobia narrative incessantly by Russian officials and Russian propaganda media for several years now, throughout our unregulated bot and troll-infested information space. “Russia is not a bad guy, but a victim” is a message that “resonates” with Americans, especially white Evangelical Christian Americans, relationships with whom Russia has been cultivating for years. In reality, this results in an uncritical tendency to reject attributing blame to Russia for acts perpetrated by Russia. This is the opposite of Russophobia; it’s ANTI-Russophobia, letting Russia off the hook over and over again.

(I bet Steve Bannon had Cambridge Analytica test such messages, by the way, before the 2016 election. And I’m sure they found they resonated with voters, precisely because Americans no longer see non-communist Russia as an adversary.)

US conservative media adds to the anti-Russophobia narrative, thanks to Trump, who refuses to even acknowledge Russia’s attack on our election. Whether this is because he is compromised or ignorant, he remains remarkably pro-Russia. America now has the ignoble distinction of having our very own propaganda media, in sync with Russian propaganda. Just look at Fox News. Once a semi-respectable conservative news outlet, Fox has so blurred the lines between news and opinion that it has transformed itself into an American propaganda machine, our own version of RT (Russia Today) or Sputnik, Russia’s English-speaking propaganda media, sycophantly singing the praises of Donald Trump and ruthlessly demonizing his opposition, including attacks on the media. It’s quite disturbing to watch. Not surprisingly, you can hear plenty about Russophobia and “anti-Russia hysteria” on any given day at any given time on this now fully coopted fake news network, steering Americans farther away from facts and the truth about Russia’s malign activities around the world, pulling a narrow swath of Americans into a disinformation hellscape on a daily basis.

Browder is rightly taken a bit aback when Simon asks him to respond to his anti-Russophobic listeners, those skeptical that Russia could really be behind so many bad acts. Browder responds with a short list of Russian aggression highlights:

BROWDER: Well, I mean, Russia was responsible for shooting down MH17. Russia was responsible for invading Ukraine. Russia is responsible for taking away the chemical weapons in Syria that they didn’t take away. Russia was responsible for having honest athletes in the Olympics when they did the whole doping program. I mean, Russia is the one who is making the trouble. Russia is really a sort of a nonentity when it comes to – the economy is the size of the state of New York. Their military budget is 5 percent of the U.S. military budget. We shouldn’t even be thinking about Russia other than the fact that they’re sort of putting their nose into every bit of terrible activity all over the world.

It boggles the mind that many people can remain skeptical about Russia’s involvement in these well-documented events, such as the invasion of Ukraine and the shooting down of civilian airliner MH17. It really speaks to the power of propaganda and the failure of our media that Americans can remain unconvinced about Russia’s aggression. Thanks to our knee-jerk rejection of blaming Russia, we have managed to give Russia the benefit of the doubt and impunity for many years, paving the way for disbelieving even Russia’s attack on the heart of our democracy.

Anti-Russophobia was at work when George W. Bush met Putin and “found him to be very straightforward and trustworthy” and got “a sense of his soul.” Anti-Russophobia was at work when Barack Obama believed Putin would remove Assad’s chemical weapons. And Anti-Russophobia is at work when the Trump administration says Putin will help solve problems and kill terrorists. And so, we looked away at invasions on neighbors, and killing of civilians. We looked away at the assassinations. That’s surely not Russophobia.

Even when confronted with Russia’s unprecedented and successful sabotage of our own election – an attack on the heart of our democracy – our media demands we hear a defense of Russia. In the NPR interview Browder was asked to essentially defend his statements about Russia being a bad actor. He just retold the horrific Bitkov story, yet Browder had to recite the many well-known and well-documented bad acts of the Kremlin, even though Simon had just said that “so many allegations” make people ever more skeptical. Remarkably, even after Browder’s recitation of recent Russian aggressive acts, the interviewer ended with yet another expression of anti-Russophobia:

SIMON: Quick question: But it’s important to get along, isn’t it?

So here’s my point: Despite daily cries of “Russophobia,” Russia still gets an enormous break from mainstream Western media, not only on its past bad acts but on current malign activity. Whether this is the result of journalistic seeking of “both sides” balance in reporting, or merely an expression of stubborn anti-Russophobia, or both, the NPR interview of Browder demonstrates that Russophobia is not reality. It is a well-played propaganda trope.

That Russophobia has become Russia’s go-to talking point to deny responsibility for everything from election interference in democracies to chemical weapons attacks in Salisbury and Syria speaks to the power of using a propaganda message that resonates deeply with people. That message is that Russia is not to blame–for whatever it’s accused of. It’s completely illogical, but the fact that this message resonates means that anti-Russophobia is still endemic in the West, so much so that we resist blaming Russia for matters for which it is clearly culpable. In even more twisted irony, as the above example shows, the more malign Russian acts, the more the Russophobia narrative resonates. That’s truly terrifying.

While anti-Russophobia sentiment has kept the West silent and slow to react to Russian aggression and bad acts staring us in the face, that’s beginning to change. After seeing Russia’s propaganda playbook whipped out again and again to deny incident after incident, government actors are moving more quickly to name and shame Russia. For example, after the brazen and shocking use of a military-grade nerve agent on Russian spy Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia in Salisbury, the British government called out Russia within days, even giving the Kremlin 24 hours to respond.

Of course, Russia wasn’t happy with that either. Kremlin officials were outraged. Russia’s UN Ambassador Nebenzia remarked “London put forth a completely absurd 24 hour ultimatum. … No one and under no circumstances can anyone talk this way, using this tone, with Russia.” And out came the accusations of Russophobia, which have become more intense and more frequent.

It’s worth remembering that cries of Russophobia resonate with some because we are still a decent and free society and can express shame for our mistakes. The irony in Russia’s Russophobia campaign is the realization that the West is not only not Russophobic, it has been anti-Russophobic, and that has meant Russia has gotten away with much of its malign conduct. If anything, the West has leaned too much in Russia’s favor for too long, failing to hold Russia accountable again and again. Now that we’re prepared to reverse this course, Russian propagandists cry Russophobia ever louder to buy time, refocus media attention, and distract and delay from the critical work of fact-finding, the results of which will inevitably hold Russia accountable for its actions.

By Paula Chertok

Paula Chertok is a linguist, lawyer and writer. She was born in Soviet Russia to Holocaust survivors from Ukraine, Belarus and Poland. She has degrees in Russian Literature, Slavic Languages, Linguistics, and Law, from Rutgers University and the University of California, Berkeley. Her work focuses on the language of propaganda, the media and civil & human rights. Follow her on Twitter @PaulaChertok