By Paul Goble, Window on Eurasia

Moscow’s handling of the case of Aleksey Navalny is so similar to the ways in which Soviet officials dealt with Academician Andrey Sakharov when the latter was in Gorky that it forces one to conclude that “Russian propaganda has finally become indistinguishable from the Soviet kind,” Andrey Loshak says.

The Russian journalist’s observation is prompted by comparing what happened with Sakharov at the time of his hunger strike in his Gorky exile in the spring of 1984 and what is happening with Navalny now not only in how the two were treated personally but how their situations were presented to the population.

In 1984, Sakharov declared a hunger strike, was isolated from his wife Elena Bonner and others for more than four months, confined to a hospital and force fed, treated with psychotropic drugs, and suffered a mini-stroke which left him with a tremor for the rest of his life. During all this, the world media tried to keep track of what was going on.

The Soviet government did what it could to make sure that no one knew the truth, with the KGB taking the lead in producing five films purporting to show “the positive sides of the life of Sakharov and Bonner in Gorky,” Loshak says. Those films were picked up in many Western outlets and had effects both planned and unplanned.

In one of the films which the Russian journalist saw, Sakharov is shown eating, an imagine intended to dispel the reports that he had declared a hunger strike and was being force fed. But the message of the film collapsed on inspection because it also showed him walking with Bonner, an impossibility since he was isolated in treatment.

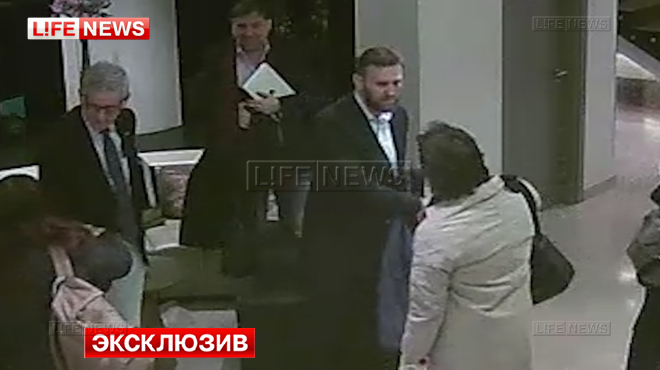

Loshak says he recalled “this propagandistic trash” when he watched a Russia Today feature about the visit of supposed rights defenders to Navalny’s place of confinement. Everything was shown as beautiful and Navalny’s condition as completely fine. Of course, “no one believed” what the Soviets said in 1984 or believes what RT is saying now.

And because of the Internet, Navalny has been more successful than Sakharov was in exposing what is being done to him and to Russia, even though the lazy and naïve then and now may accept the regime’s slick propaganda efforts.

By Paul Goble, Window on Eurasia