By Halya Coynash, Human Rights in Ukraine

While whole villages, sometimes regions, come out to bid farewell to slain Ukrainian soldiers, Russians killed are likely smuggled back in Moscow’s supposed ‘humanitarian convoys’ or lie in unnamed graves in the Rostov oblast near the militant-controlled part of the border.

Valentina Melnykova, Head of the Union of Russian Soldiers’ Mothers Committees, stresses that Russia has followed the Soviet tradition of not publicizing fatalities. This, however, is the first war she is aware of where the families of young men killed are not approaching the committees for help. She believes the explanation may lie partly in the ‘insurance’ payments the families get, but acknowledges that it is hard to understand “why Russian families agreed so easily to this silence, to this anonymity”.

One mother has now got in touch, asking for help to get her son’s body back for reburial in Russia. Melnykova is convinced that others will start coming forward, as they experience problems with their health, when the benefits they were promised don’t emerge.

For the moment, however, the revelations about the Pskov paratroopers killed in Donbas in August 2014, about other deaths and about attempts to hush them up have not reached the public realm since 2014.

Melnykova says that her committees assume a figure of at least 1,500 “Russian so-called volunteers, in fact, Russian conscripts, soldiers, officers”. That figure is based purely on experience that there tends to be a correlation between deaths on both sides, not on knowledge about specific deaths.

Melnykova told the BBC Ukrainian Service there is no chance at present of calculating the number of deaths and calls the situation “terrible”.

“From the beginning of military action, Russian soldiers were sent there without documents, without identification tags, depersonalized, in accordance with unknown orders and with unclear status. It’s impossible in principle to give an exact calculation, there can only be folklore methods of calculating.”

There are others who have attempted such calculations, such as Yelena Vasilyeva, whose Cargo 200 has, since 2014, come out with by far the highest figures. The information is, however, collated without real checks being carried out, and is widely distrusted for that reason alone.

Officials from Ukraine’s Defence Ministry point out that a major difficulty lies in determining whether those killed were locals with Ukrainian citizenship, or Russians. The SBU and Ukrainian Military Intelligence told the BBC that they believe there are 35-40 thousand fighters in the self-proclaimed ‘Donetsk and Luhansk people’s republics’ [DPR, LPR, respectively], with 4 – 5 thousand – Russian military servicemen. It is likely that many others are also Russian, but it is difficult to determine the nationality, both of those now fighting, and those killed.

One of the factors making it particularly difficult is that military personnel sent to Donbas are given fictitious names and documents.

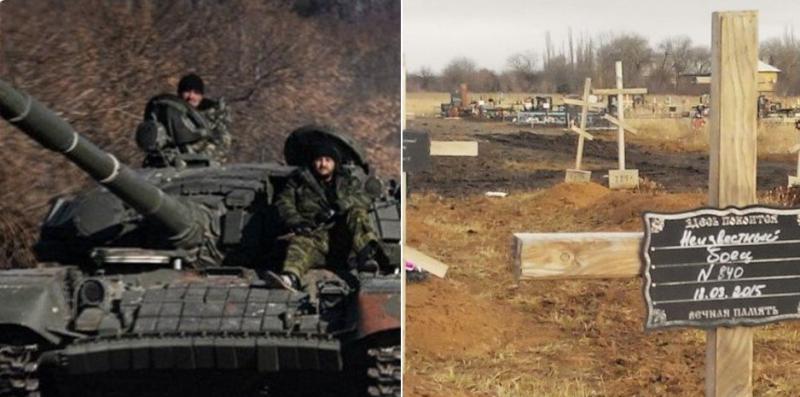

Graves

Russia denied from the beginning that it was behind the military conflict in Donbas. It continues to claim, for example, that soldiers captured 30 kilometres into Ukrainian territory ‘got lost’, that two military intelligence officers seized after the killing of a Ukrainian soldier had ‘resigned’ months earlier and that the sophisticated tanks and other equipment used by Kremlin-backed militants “were found in Donbas mines”.

The truth began emerging in late August 2014, with news of the death in Donbas of the major part of a Pskov paratrooper regiment. At that stage, the questions were still being asked, at least by certain independent publications. Vedomosti, for example, “Is Russia fighting in Ukraine and if so, then on what grounds? If not, then who is in those freshly-dug graves or giving testimony at SBU interrogations?”

The shenanigans began soon after the media began reporting such deaths. Novaya Gazeta explained that the wife of Leonid Kichatkin had reported his death on Aug 22, 2014 on VKontakte. By the next day Leonid’s page had disappeared, and when Novaya rang the number that had been given, the woman who was supposedly Leonid Kichatkin’s wife insisted that her husband was alive, well and right next to her. A man then took the phone and confirmed that he was Kichatkin.

The Novaya journalist found Leonid Kichatkin’s newly dug grave in the Vybuty cemetery outside Pskov. The photo is that seen on his wife’s VKontakte page (more details here).

The first indications came at that time that the so-called ‘humanitarian convoys’ that Russia was breaking international law by bringing into Ukraine without checks might be used to return the bodies of soldiers killed, as well as taking military equipment and ammunition into Donbas.

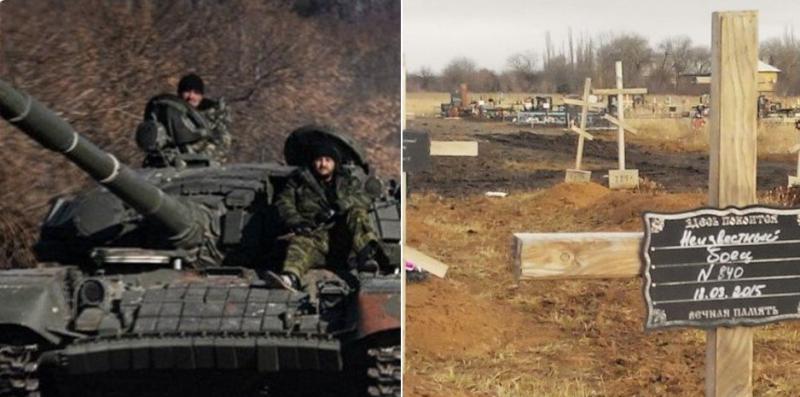

In fact, in August 2014, there were witnesses videoing Russian tanks, heavy artillery and men travelling towards the Russian-Ukrainian border (and not returning) See: An Invasion by any other name.

While it is quite conceivable that ‘humanitarian convoys’ are used to return the bodies of military personnel, it seems likely that many mercenaries do not even get a proper grave (see: Unmarked Graves of Russia’s Undeclared War),

Enforced silence

The publicity was clearly not to the Kremlin’s liking, and on May 28, 2015, Russian President Vladimir Putin issued a decree classifying information about Russian military losses during “special operations in peacetime”, thus potentially enabling prosecution and imprisonment for divulging details about the deaths of Russian soldiers in eastern Ukraine.

Russian soldiers have also ended up imprisoned for refusing to fight in a war that Russia denies waging (details here).

Russia’s chief military prosecutor has refused to investigate the death of 159 Russian soldiers who are believed to have been killed in Russia’s undeclared war against Ukraine. The prosecutor’s office asserts that checks were carried out into all deaths from the beginning of 2014 to mid-2015, and no infringements were found. This view was categorically not shared by Sergei Krivenko and other members of the President’s Human Rights Council. On Dec 8, 2015, they formally demanded an official answer as to the circumstances in which the soldiers had been killed. The human rights activists pointed out also that there had been a sharp increase in such unexplained deaths during the second half of 2014. This coincided with the first publicized reports of soldiers’ deaths in Donbas, as well as a major escalation in Russia’s direct military involvement in eastern Ukraine.

Putin has, in fact, admitted to military involvement in Donbas. In answering a question from Ukrainian journalist Roman Tsymbalyuk in December 2015, Putin claimed that Russia had never said that they did not have people in Donbas “resolving various issues”, including in the military sphere. But there are no regular forces, he asserted, and asked the audience to “feel the difference”. Those who find it difficult to perceive the alleged distinction would be no wiser after his assertion that Russia was ‘forced’ to intervene back in October 2016.

There have been various forms of pressure placed on civic activists – from criminal proceedings to physical attacks. Although there were numerous subjects on which Boris Nemtsov’s honesty rang out, he was one of a very small number of prominent Russians who spoke out unequivocally from the outset against Russia’s invasion of Crimea and war in Donbas. He was planning a report on the war when gunned down near the Kremlin on Feb 27, 2015. The report was later put together by his friends and colleagues.

While Russia arms and provides fighters for its undeclared war in Ukraine, and lies about Russian soldiers’ deaths, the funerals continue almost daily of Ukrainian soldiers killed in Donbas. There is no point in expecting conscience from those in the Kremlin, but the families of Russian soldiers who have died, and the Russian journalists who have fallen silent since Putin’s decree would do well to watch how Ukrainians honour Ihor Novak, Oleh Yurdyha, Ivan Sotnyk and thousands of other slain defenders of their homeland.

By Halya Coynash, Human Rights in Ukraine