By Artem Laptiyev

In February the Russian State Duma Council will consider an appeal to President Vladimir Putin to recognize the self-proclaimed Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics. Moscow has long been working on the issue of integrating the temporarily occupied Donbas and has gradually created the legal and economic basis for this step. Taking occupied Donbas under its influence is not a new idea for Russia, it has been dreaming about it since the moment Ukraine declared independence. The Kremlin tried to use the 1990s miners’ protests to that end, in the 2000s Moscow supported pro-Russian politicians at the Severodonetsk secession congress and in the 2010s Moscow wanted to take Donbas by force. At the end of last year, a new plan was announced in the Russian Duma – in order to annex Donbas, the 1922 People’s Commissars Council Act which made Donbas part of the Ukrainian SSR must be invalidated. Different methods, but the goal remains the same. In this article we analyze Russian attempts to snatch Donbas from the moment of Ukraine’s declaration of independence thirty years ago to the present day.

Return control over Ukraine

After the collapse of the Soviet Union and unsuccessful attempts to create a new political association with Ukraine, Russia did not abandon its imperial ambitions, plans which would be nothing without Ukraine, therefore it was necessary to return it under its control – in its entirety or in parts. However, the declaration of Ukraine’s independence followed by a referendum that confirmed overwhelming support for this step as well as internal economic and political problems in Russia itself, left Moscow unable to pursue such ambitions. At least for a while.

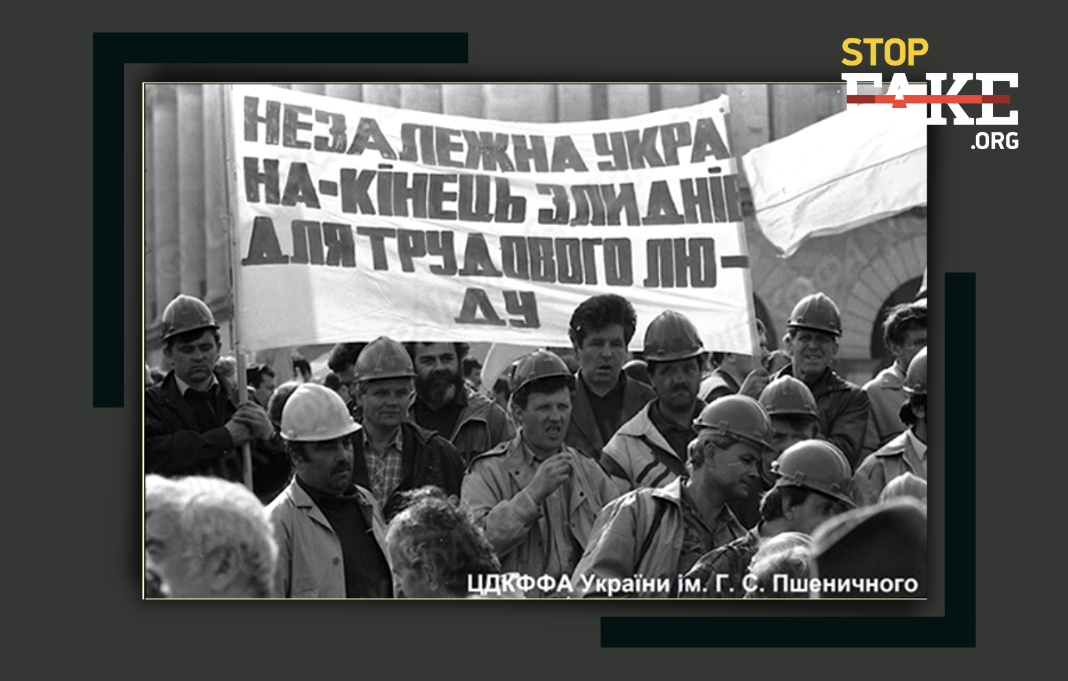

Luhansk and Donetsk area residents played an important role in the collapse of the Soviet Union and the formation of an independent Ukraine. In July 1989, on the eve of the USSR’s disintegration, miners in Donbas began a series of mass protests. One of their main demands was the improvement of working conditions and a wage increase. Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev reached out to the miners and invited them for talks in Moscow, where their conditions were temporarily satisfied. However, in the spring of 1991 they went on strike again. By this time, what the miners wanted had expanded to include political demands as well: the resignation of Mikhail Gorbachev, the dissolution of the Congress of People’s Deputies, and the constitutional designation of Ukraine’s Declaration of State Sovereignty (more on this can be found in the Chuesh hurkit kasok? (Do you hear the roar of the helmets?) section of the 30th anniversary of Ukraine’s independence project Our 30. Live History.

Striking Donbas miners on October Revolution Square, Kyiv, April 16, 1991.

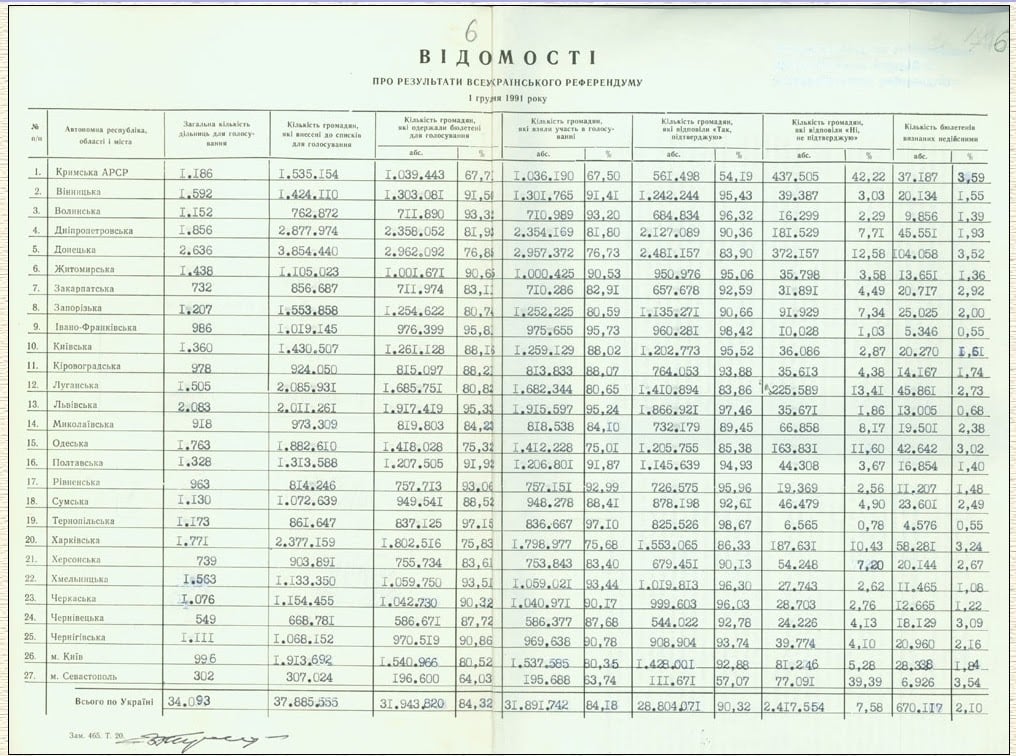

The Ukrainian referendum confirming Ukraine’s August 24, 1991, Declaration of Independence reflected the mood of the miners and other Donbas residents. More than 83% of Donetsk and Luhansk area voters supported Ukrainian independence in the referendum.

However, Ukraine’s proclamation of independence did not solve the economic problems that had festered in the last years of the USSR. Rising prices, low wages, poor working conditions, this is just the tip of the iceberg of the problems which forced Donbas miners to continue striking throughout the 1990s, but now in an independent Ukraine. These miners’ strikes were now the internal problem of an independent Ukraine. But already in the 1990s the Kremlin was trying to take advantage of the consolidated miners’ movement and the Ukraine’s poor economic situation to maintain its influence. This is how Ukraine’s President Leonid Kuchma saw the situation.

Declassified US foreign policy documents from the administration of the 42nd US President Bill Clinton contain several documents relating to Leonid Kuchma. One of them is the transcript of a February 21, 1996, Oval Office conversation between Kuchma and Clinton. The transcript makes it clear that even then the Ukrainian president saw the Kremlin’s intention to return Ukraine “to Russian control.” Kuchma told Clinton about economic pressure from Russia, in particular “complaining” that Moscow had cut Ukraine off from the public electricity grid, forcing it to use more natural gas. At that time, according to Kuchma, this led to the closure of half the country’s enterprises. In addition, Kuchma claimed that Russia promoted labor unrest in Ukraine, in particular, he mentioned mining protests:

“While declaring in public their friendship and love, the Russians are doing everything possible to suppress us and drive us to our knees. Any delays in our cooperation with the IMF, the World Bank and other creditors will only exacerbate our situation. The Russians provoked the strikes by Ukraine’s coal miners, they sent representatives to virtually all of Ukraine’s mines.”

According to Kuchma, he regarded all these actions as the Kremlin’s attempts to return Ukraine to its influence:

“Russia wants Ukraine within the Russian control structure. Russian attitudes today are completely different from just one year ago. In fact, this change in attitude is the direct result of the Russian perspective that we are beginning to make progress on our own.”

Of course, this does not mean that it was only Russia behind the mining protests in Ukraine. Kuchma did not question the goals and demands of the Donbas miners, but only pointed out to Clinton that the Kremlin had a direct interest in an unstable Ukraine. Already in the 1990s Russia was trying to take advantage of the Donbas population and exploit the economic problems of the region in order to achieve its imperial goals.

Kuchma’s 1996 pronouncements about Russia wanting to control Ukraine are no secret, he spoke about this publicly as well. In 2003 President Kuchma published a book entitled Ukraine is not Russia in which he examines the historical aspects of the formation of Ukrainian independence. In the book Kuchma addresses Russian politicians who do not want to understand the difference between Ukraine and Russia. The book with its unequivocal message captured in its title, was a public manifestation of the dissatisfaction of the Ukrainian elite with the desire of Russian politicians to return Ukraine to Moscow’s orbit.

The Severodonetsk congress

Donbas survived the challenges of the 1990s, challenges that were replaced by new tests and confrontations. In the 21st century the Kremlin once again tried to take advantage of political instability in Ukraine to return the country to Moscow’s fold. Preliminary results of the 2004 Ukrainian presidential elections suggested that Viktor Yanukovych, the pro-Russian presidential candidate had won. However, the public questioned the results along with the lack of transparency and fairness of the entire electoral process. This distrust became the Orange Revolution, months of protests in central Kyiv that resulted in new elections and a victory for pro-Western candidate Viktor Yushchenko. In response, Viktor Yanukovych and his pro-Russian political allies, including Russian politicians, held a congress in the eastern Ukrainian city of Severodonetsk threatening secession.

The congress was held on November 28, 2004 in the Severodonetsk Ice Palace. The meeting unilaterally recognized the victory of Viktor Yanukovych. An even more important outcome of the meeting were calls to separate Donbass from Ukraine. In the event of Viktor Yushchenko’s victory, the head of the Donetsk Regional Council, Boris Kolesnikov, proposed creating “a new federal state — the South-Eastern Republic with its capital in Kharkiv.” There were also ideas to create a separate republic in the Donbas or even join Russia, the Voice of America reported. The whole show was actively supported by Russia: Yuri Luzhkov, the mayor of Moscow attended the congress and declared his full support for the pro-Russian candidate Yanukovych.

The congress adopted a resolution calling for a referendum to be held on December 12, 2004, on granting the Donetsk and Luhansk regions the status of autonomous republics within a federal Ukraine. At that time the matter did not go any further than a resolution. Victor Yushchenko won the presidential election, and despite Moscow’s support, Yanukovych and his pro-Russian party, did not dare to go further.

Both in the 1990s and in the 2000s, Luhansk and Donetsk area residents did not support the Kremlin’s ideas to take Donbas “under a Russian wing”. The same cannot be said for 2014, by then Russia had abandoned the idea of a “soft return” through referendums and local irredentism and resorted to force. StopFake wrote about this in detail in “The Novorossiya Project: Birth, Death and Historical Myths”. Today Russia may decide to complete the process it began in the 1990s and recognize the so-called Luhansk and Donetsk People’s Republics that it created as its own.

Recently speaking in Donetsk, Margarita Simonyan, editor-in-chief of the RT television channel proclaimed: “Mother Russia, take Donbas home!”

Perhaps such rhetoric from the Kremlin and its messengers is just a political game played out against the backdrop of a military buildup near the Ukrainian border and Putin’s ultimatum not to expand NATO. But regardless of whether the Kremlin decides to openly recognize its occupation of Donbas or simply continue with the current stalemate, one thing is worth remembering, ever since Ukraine’s declaration of independence thirty years ago, Russia has always looked for and created opportunities to destabilize Ukraine and subjugate it, if not the entire country, then at least the Donbas region.