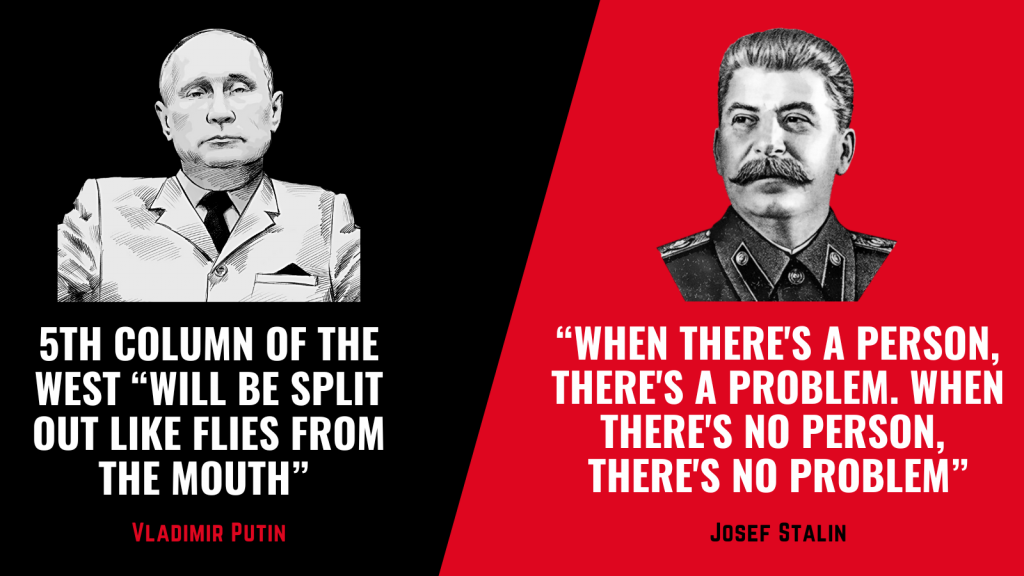

Like most autocratic leaders, Putin needs enemies and victories, both abroad and at home. Putin’s speech on 16 March, three weeks after the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, turned to the domestic scene. He called for “cleansing” of Russian society of the fifth column, “bastards and traitors”, and used the infamous “spit-them-out-like-flies” quote. More arrests of high-ranking officials have since occurred. Media report some 150 arrests just in the central structures of the FSB, Russia’s security service.

The current situation cannot be equated to the Stalin era of the 1930s where национал-предатели [traitors of the nation] or “enemies of the people” were identified on every corner to be blamed for any and all problems. Nevertheless, the tone of the public debate in Russia has started to be tougher than anything known since WWII, including in the 1960s to the early 1980s, the Soviet Union’s peak years under Leonid Brezhnev.

The current torrent of disinformation narratives alleges that the West is ganging up against Russia and luring Russians with a weak morale, or that the “Ukrainian Nazis” are planning or committing atrocities against Donbas residents. Putin’s spokesperson Dmitry Peskov blamed everything on “the Nazis supported by the West” in a recent interview with Sky News. The sinking of the Russian navy’s missile cruiser “Moskva” added fuel to the domestic debate with calls for even more bombing of Ukraine, and to rally behind the flag inside Russia.

Political repression in today’s Russia is steadily on the rise. The official Russian list of “extremists” keeps growing. By August 2021 already, 410 political prisoners had been registered.

Domestic protests

Serious political dissent started brewing in Russia 2005 with the so-called dissenters’ marches which lingered on until 2008. A second wave of popular protest developed across the country from 2011 to 2013 in the wake of the 2011 parliamentary elections that were distorted and plagued by ballot-stuffing and other kinds of fraud. More arrests took place. Police brutality was noticeable. Moscow blamed the West for supporting the opposition, alleging the aim was to disrupt or even destroy Russia (see several cases in our database).

The Kremlin boosted the repressive campaign against the opposition following its illegal annexation of Crimea in 2014. One of the most vociferous critics of Putin, Boris Nemtsov, was assassinated in the centre or Moscow in 2015. An investigation showed that five Chechens were guilty of the crime, but some facts indicate that the FSB might have been involved in the murder.

Opposition leader Alexei Navalny was arrested in 2021 and sentenced to nine years in prison. He had returned to Russia from Germany, where he had been convalescing after Putin’s agents poisoned him with the Novichok toxic agent in the Siberian city of Tomsk. Moscow likely expected him to stay abroad, but he chose to return. Navalny is a charismatic opposition leader, so Putin’s steps illustrate a fear of losing control.

Teenagers can also pose a threat to Putin’s Russia, especially if they play a computer game in which they plan to destroy the FSB building. One of them, Nikita Uvarov, 16, was jailed in February 2022 for five years for planning a virtual explosion. Two others received suspended sentences for cooperating with investigators. When Uvarov was detained, he was just 14. There was a similar case with young people who were charged with “organising an extremist group intending to carry out crimes of extremist character” and sentenced to jail terms in 2020. They had set up an organisation named “New Greatness” in 2017. The young people were discussing politics during their meetings, which investigators and prosecutors found sufficient for a criminal case.

Foreign targets

Alongside fighting his domestic rivals, Putin’s system has been actively tackling opponents abroad. Ex-KGB spy Alexander Litvinenko was poisoned by radioactive polonium and died in 2006 in the UK. He had been highly critical of Putin’s regime and fled to the UK in 2000. An official British inquiry found that “the FSB operation to kill Litvinenko was probably approved by [then FSB director Nikolai] Patrushev and also by President Putin”. Questions about the case are rejected by Moscow as “Russophobia”.

Fugitive Russian oligarch Boris Berezovsky was found dead in the UK in 2013. It was reportedly a suicide, but some sources suspected that it was a murder. Berezovsky had been very active in anti-Kremlin activities since he emigrated to the UK. There is no direct proof of Russian involvement in this case, but questions still remain unanswered.

Sergei Skripal, another former Russian spy, and his daughter Yulia were reportedly targeted by Putin’s hitmen in Salisbury, UK, in 2018. The British authorities discovered that the Skripals had been poisoned with the neurotoxin Novichok and Russia was “highly likely” behind the attack. The attempts by Moscow to deflect and deny responsibility remain among the most prominent examples of pro-Kremlin disinformation campaigns – see the many cases here.

Draconian legislation

Disinformation and manipulation is also engineered by changing the ground rules of who can speak and how they can speak.

Russia adopted legislation on “foreign agents” in 2012. According to the new legislation, non-governmental organisations and individuals are considered foreign agents if they engage in political activity and receive any foreign funding. It seriously restricts their work in Russia.

A law on criminalising insults to authorities and state symbols was enacted in 2019. A critical comment against any official, or the president, can lead to a fine or imprisonment if a court considers it an insult.

A law punishing the distribution of so-called “false news” (anything not from official sources) about Russia’s “special military operation” [the war in Ukraine] was adopted on 4 March 2022. Same with reporting numbers of casualties higher than the official count, which stood at 1,351 soldiers before the sinking of the cruiser “Moskva”. Defeatism or low morale is not tolerated.

Getting into conflict with any of these regulations will usually bring either a closure of the organisation, as was the case with Memorial or media outlets such as Novaya Gazeta, or land you in prison like Alexei Navalny.

Another way to get targeted is a “catch all” option: to be labelled as “an extremist organisation or person”. This is an administrative designation requiring no court decision. So far, for example, more than 11 leading persons from Navalny’s organisation have been registered as such. It implies that your property is de facto frozen, that people cannot do business with you, that you lose you job – one step before prison.

Josef Stalin is attributed this brutal quote: “When there’s a person, there’s a problem. When there’s no person, there’s no problem.”