Assessing the propaganda role of the Kremlin’s “news” wire

By Ben Nimmo, for DFRLab

On February 16, 2018, the U.S.-based company responsible for the Russian government’s “Sputnik” online service in America registered under the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA).

FARA was created in 1938 to expose Nazi propaganda in the United States. It obliges “every agent of a foreign principal, not otherwise exempt, to register with the Department of Justice” and to label their publications with a “conspicuous statement that the information is disseminated by the agents on behalf of the foreign principal.”

In the case of Sputnik, RIA Global LLC registered as an agent of Russian Federal State Unitary Enterprise “Rossiya Segodnya International Information Agency,” insisting that Rossiya Segodnya “acts completely independently based on its editorial policies.”

Despite that claim, the evidence shows that Rossiya Segodnya and Sputnik are overwhelmingly subservient to Russian state interests and foreign policy — not just defending the Kremlin, but attacking and interfering in Western democracies.

Their official tasks include “securing the national interests of the Russian Federation,” and their performance lives up to that goal.

Foundation and Charter

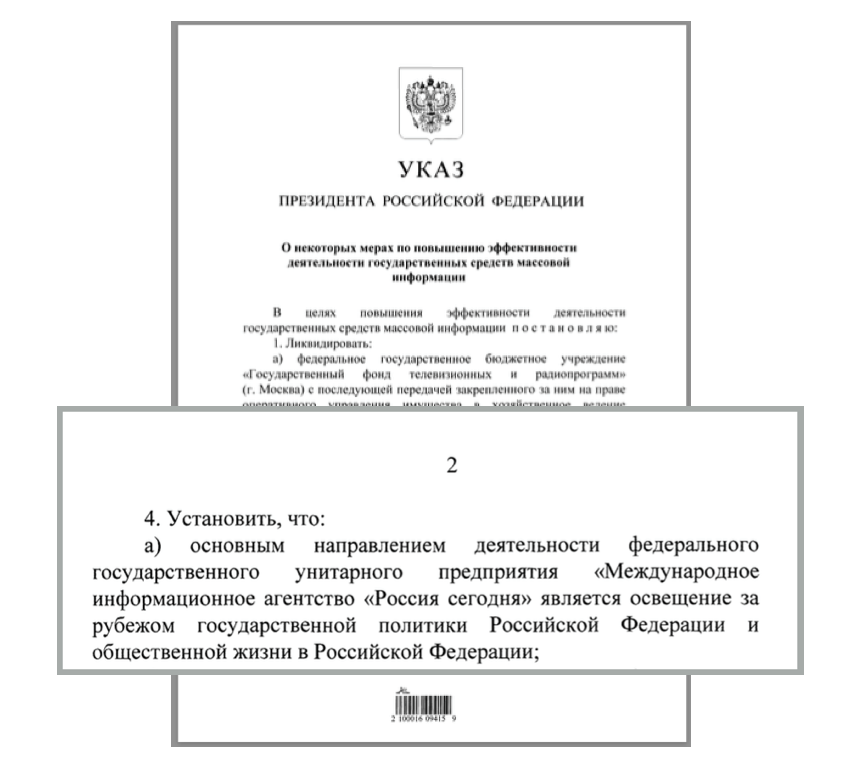

The Rossiya Segodnya news agency was created by executive order of Russian President Vladimir Putin on December 9, 2013. The order took the formerly state-run, but editorially respected, RIA Novosti news agency, and the Voice of Russia radio station, and transferred them to the new agency, whose name means “Russia Today.”

Paragraph four of the executive order defines the new agency’s “main direction of activity” as “reporting abroad on the state policy of the Russian Federation and public life in the Russian Federation.”

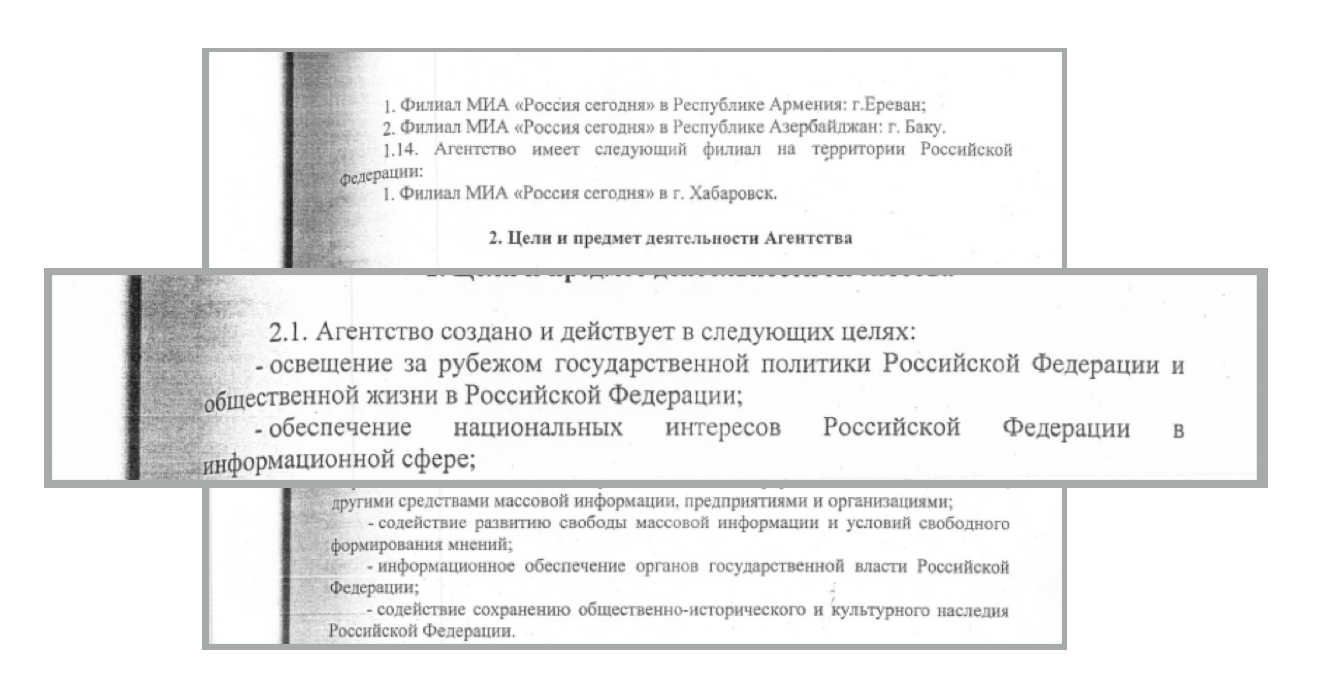

The same month, Rossiya Segodnya registered with the Moscow tax authorities. That registration included a copy of the agency’s founding charter, which is available online via the Federal Agency for Press and Mass Communications of the Russian Federation.

According to paragraph 2.1 of the charter, Rossiya Segodnya was created and acts with the following goals:

“Reporting abroad on the state policy of the Russian Federation and public life in the Russian Federation;

Securing the national interests of the Russian Federation in the information sphere.”

Both these tasks position Rossiya Segodnya as a government communications agency. In particular, the task of “securing the national interests of the Russian Federation in the information sphere” marks Rossiya Segodnya as an instrument of Russian state power — not an independent journalism outlet.

For Russia, With Love

The role of Rossiya Segodnya, and thus of Sputnik, as state mouthpieces is confirmed by the agency’s director, Dmitry Kiselev, who was sanctioned by the European Union in 2014 as the “central figure of the government propaganda supporting the deployment of Russian forces in Ukraine.”

A few days after Putin signed the executive order creating Rossiya Segodnya, Kiselev addressed a meeting of journalists at RIA Novosti. One journalist filmed the speech on his mobile phone; the original post was deleted from YouTube, but not before Interpreter magazine provided a translation.

The speech includes this comment:

“We are a state agency which exists on government funds. I am not against other points of view, they can be diverse even within this field about which I am speaking. But if we are to speak about traditional politics, then of course we would like it to be associated with love for Russia.”

The following year, when Rossiya Segodnya officially launched Sputnik as its export brand, Kiselev explained the outlet in terms of Russia’s geopolitical opposition to the United States:

“There are countries that impose their will on the West and on the East. Wherever they interfere, blood flows, civil wars break out, ‘color revolutions,’ and even countries break up: Iraq, Libya, Georgia, Ukraine, Syria … Many already understand that it is not necessary to assist the Americans in all this. Russia offers a model of the world for the good of humanity. We are for a multicolored, multi-layered world, and in this we have many allies, therefore our media group is launching a new global brand, Sputnik.”

This places Sputnik explicitly in the context of Russia’s geopolitical ambitions, and its opposition to the United States: “therefore our media group is launching a new global brand, Sputnik.”

By June 2016, Kiselev was comparing the agency’s role directly with that of Putin, as an advocate for, and defender of, the Russian government’s policy, in a conference in Moscow in June 2016:

Source: YouTube / Россия 24)

Translated from Russian, he said:

“We try to explain our positions to the world — yes, of course, we try to explain Russia’s actions, openly, of course. But all Putin does is to explain Russia’s actions everywhere, in all forums, in all press conferences, Direct Lines, in his endless interviews. He does it tirelessly, meets his colleagues. What’s that, propaganda? Of course not, it’s just transparency, that’s what it is, transparency, he tries to explain the logic of Russia’s actions.”

This erases any of the distinctions which should exist between a head of state, whose task is to represent the country and its government, and a news outlet, whose task should be to report independently of the government line.

Confirmation that this approach is not confined to the general director, but is expected of all staff, comes from the Rossiya Segodnya style guide. Style guides are a common feature of news agencies, and explain the details of the “house style,” from the mission to the use of punctuation.

According to a copy of the style guide shared with @DFRLab by a former employee, much of the Rossiya Segodnya text is consistent with other outlets’, insisting on fact-checking, accuracy, and balance.

However, it includes, under the heading “Credibility,” the following crucial paragraph:

“It is also important that our journalists maintain allegiance to the larger national and public interest. Our main goal is to inform the international audience about Russia’s political, economic and ideological stance on both local and global issues. To this end, we must always strive to be objective, but we must also stay true to the national interest of the Russian Federation.”

Defenders of RT and Sputnik regularly argue that this is no different from the charters of other international state-connected broadcasters, such as the BBC. This is false. The BBC Charter lists five “public purposes,” of which the fifth is “To reflect the United Kingdom, its culture and values to the world.”

The underlying text explains that those “British values” are “accuracy, impartiality and fairness,” and that the broadcaster should aid “understanding of the United Kingdom as a whole, including its nations and regions where appropriate.”

“Reflecting” the UK as a whole is a very different mission from “reporting on the state policy of the Russian Federation,” let alone “securing the national interests of the Russian Federation in the information sphere.” It is the essential difference between a public service broadcaster, and a state one.

The Rossiya Segodnya founding documents and style guide, and Kiselev’s comments, are mutually consistent. They describe an outlet whose purpose is to communicate on behalf of, and in defense of, the Russian government — rather than being independent of it.

Selling The Product

One of the most obvious ways in which Sputnik fulfils this purpose is its coverage of the Russian state arms industry.

Analysing the industry would be a justifiable part of any outlet’s output. Sputnik’s coverage, however, reads more like advertising. For example, one piece, on November 10, 2017, was headlined, “Russian military producer: S-400 systems working flawlessly in Syria.”

It quoted Sergei Kornev, the head of the aerospace division of Russia’s state armaments exporter, as saying that Russia’s modern S-400 surface-to-air missile system was working “impeccably” in Syria, and that Middle Eastern countries were “paying great attention” to Russia’s weaponry in Syria. Kornev was the only commentator quoted.

This is not balanced journalism; it is not even news. Praising Russian weapons is Kornev’s job: it would be newsworthy if he failed to do it. Sputnik’s piece serves no apparent purpose other than to promote Russian air defense systems to a foreign readership.

Another piece, published on March 27, 2018, had the equally enthusiastic headline, “Why Russia’s air defense is second to none.”

Listed as an opinion piece, this article began with the following sentence: “Russia attaches great importance to its air defense systems, which could be regarded as second to none, Sputnik contributor Andrei Kots notes.”

The Sputnik piece appears to be largely a translation of a Russian-language original by RIA Novosti writer Andrei Kots, published on March 26: the structure, sources, quotes and main points are all identical.

However, nowhere in the current version of the Russian-language piece is there any sentence which could be construed as calling Russia’s air defenses “second to none.”

It is therefore unclear where Sputnik found its headline quote, or whether the outlet simply made it up in an effort to boost the reputation of Russia’s arms industry.

By contrast, recent Sputnik articles on Western weaponry included reports that half of the United States’ F-35 planes are “not ready for battle,” that a new S-97 helicopter “failed to impress,” and that Russia’s Admiral Kuznetsov aircraft carrier, built in Soviet times, has a “big advantage” over Britain’s new aircraft carrier, the Queen Elizabeth.

Criticism of military equipment is an important feature of journalism. However, Sputnik’s criticism seems restricted to Western systems. Placed alongside its lavish praise for Russian systems, this gives the strong impression that Sputnik’s job is to make Russian arms exports look good.

Bring Out The Bikinis

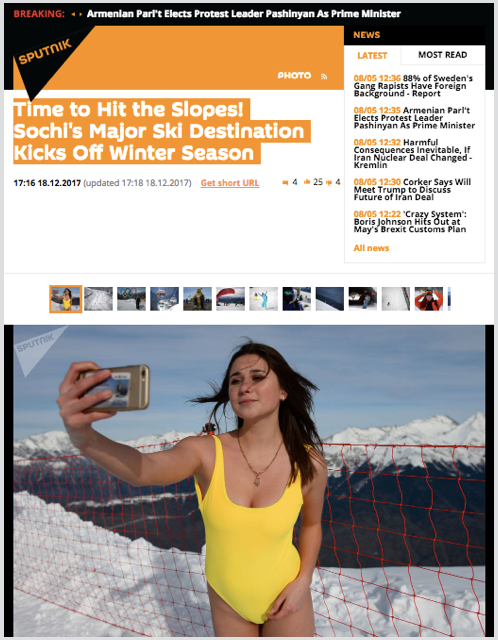

Sputnik also praises Russian tourist destinations and the Russian tourism industry, often using pictures of women in bikinis to do it.

A photo montage published on December 18, 2017, proclaimed the opening of the Rosa Khutor ski resort, “one of the main ski resorts in Russia’s Krasnodar Region,” and stated that “Countless numbers of amateur and advanced skiers and snowboarders flocked to Rosa Khutor to have some winter fun as the season started.”

The top picture showed a young woman in a swimsuit taking a selfie — a classic piece of visual marketing.

Other photo montages dwelt on “bikini slalom” ski events in the Russian resorts of Sheregesh and Sochi, and the “Khibiny-Bikini festival” in the Khibiny region, while articles under the “tourism” tag included claims of tourists “flocking” to Chechnya and Russia more broadly.

A Google search for the term “bucket list” limited to the Sputnik site returned a “bucket list of must-see destinations in Russia,” a list of “Russia’s most irresistible destinations,” and a list of “Red Square and other sights in Europe ‘you must see before you die.’”

The latter list was based on a Daily Telegraph article which listed 30 top European destinations, under the headline “30 places in Europe you must see in your lifetime.” Red Square was thirteenth on the Telegraph list, but the only one named in Sputnik’s headline.

As the Telegraph story shows, bucket lists are standard fare for news outlets. However, the Google search did not reveal any Sputnik bucket lists or photo montages of destinations in other countries, again marking it out as an apparent advertising agency for Russian destinations.

Political Messaging

As with bombs and bikinis, so with politics: Sputnik amplifies and validates Russian government positions, posting opinion pieces which echo the Kremlin’s stance, or interviewing external speakers who support the Kremlin line in a way that brings out their opinions without challenging them.

Some of these opinions come with disclaimers which say that they do not reflect Sputnik’s official position. However, the opinions are so routinely pro-Kremlin and anti-Western, and so rarely anything else, that they effectively constitute an editorial line.

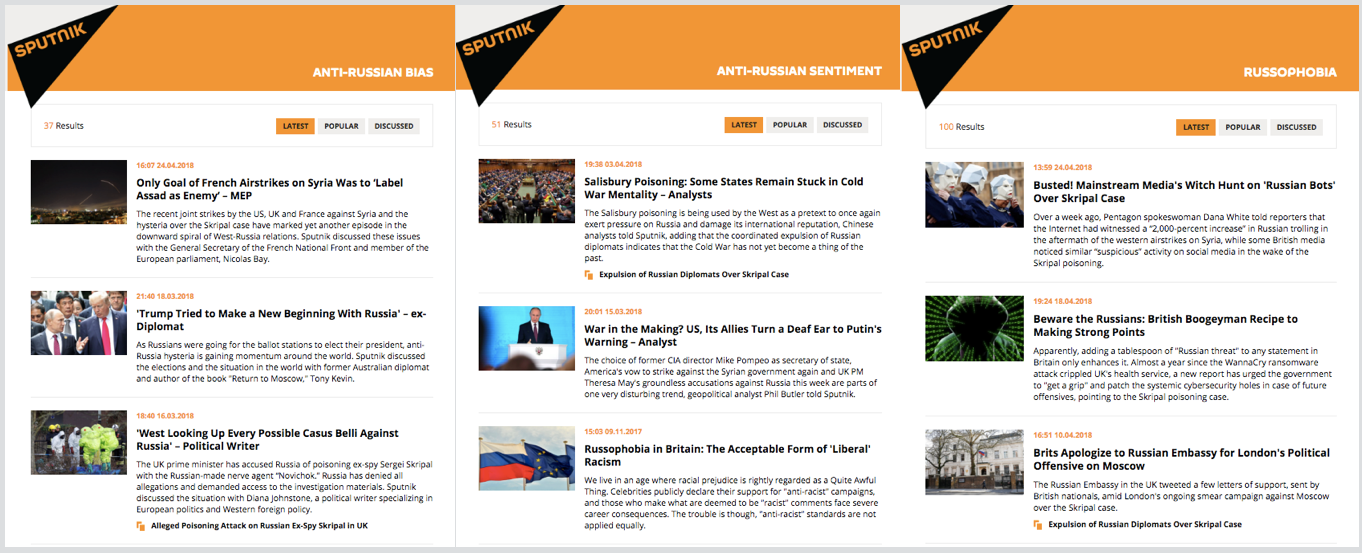

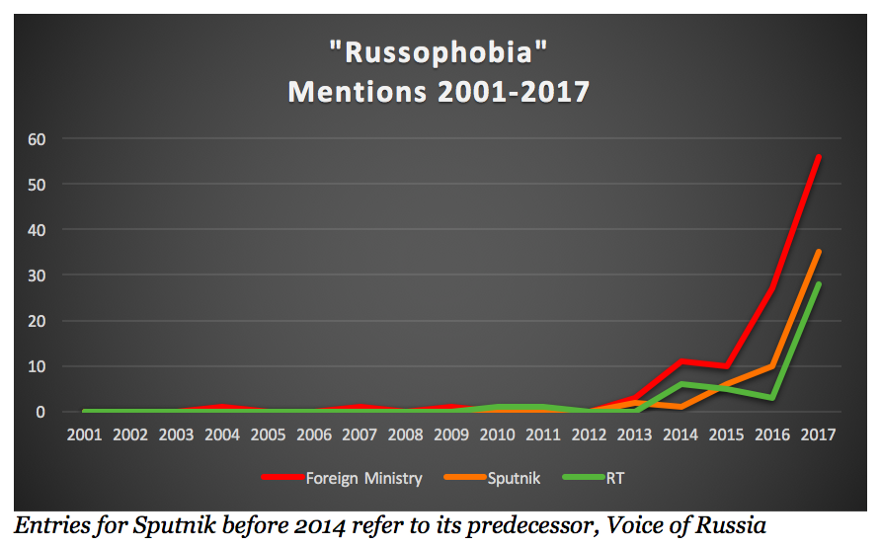

One of the most glaring examples is Sputnik’s use of the word “Russophobia,” which it deploys so consistently that it is actually a tag on the Sputnik website, alongside “anti-Russian bias” and “anti-Russian sentiment.”

This narrative of victimization has been a stock Kremlin defense ever since the illegal annexation of Crimea in March 2014, as @DFRLab has reported; it ignores the wealth of evidence which shows that, for example, Russia provided the weapon which shot down Malaysian Airlines flight MH17 over Ukraine in 2014, shelled civilians in Mariupol, Ukraine in 2015, and interfered in the U.S. presidential election in 2016.

Sputnik commentators and hosts often use official Kremlin terminology to characterize events in which Russia is involved, without acknowledging that those characterizations are, at best, disputed.

For example, in a Sputnik radio broadcast on December 30, 2017, in the U.S., the host referred to the “success of Russia’s anti-terrorism military intervention in Syria.” This is the Russian government’s standard term for the operation, despite the evidence that Russia’s main target has been Syria’s domestic opposition, not “international terrorist groups.”

The same host spoke of the defeat of Islamic State “at the hands of the Syrian and Iraqi militaries, the Russian aerospace forces and Iran and its allied militia,” entirely omitting the role of the U.S.-led international coalition in Iraq and eastern Syria, and claimed that “Russia’s all about stabilising, balancing and bringing everybody together.”

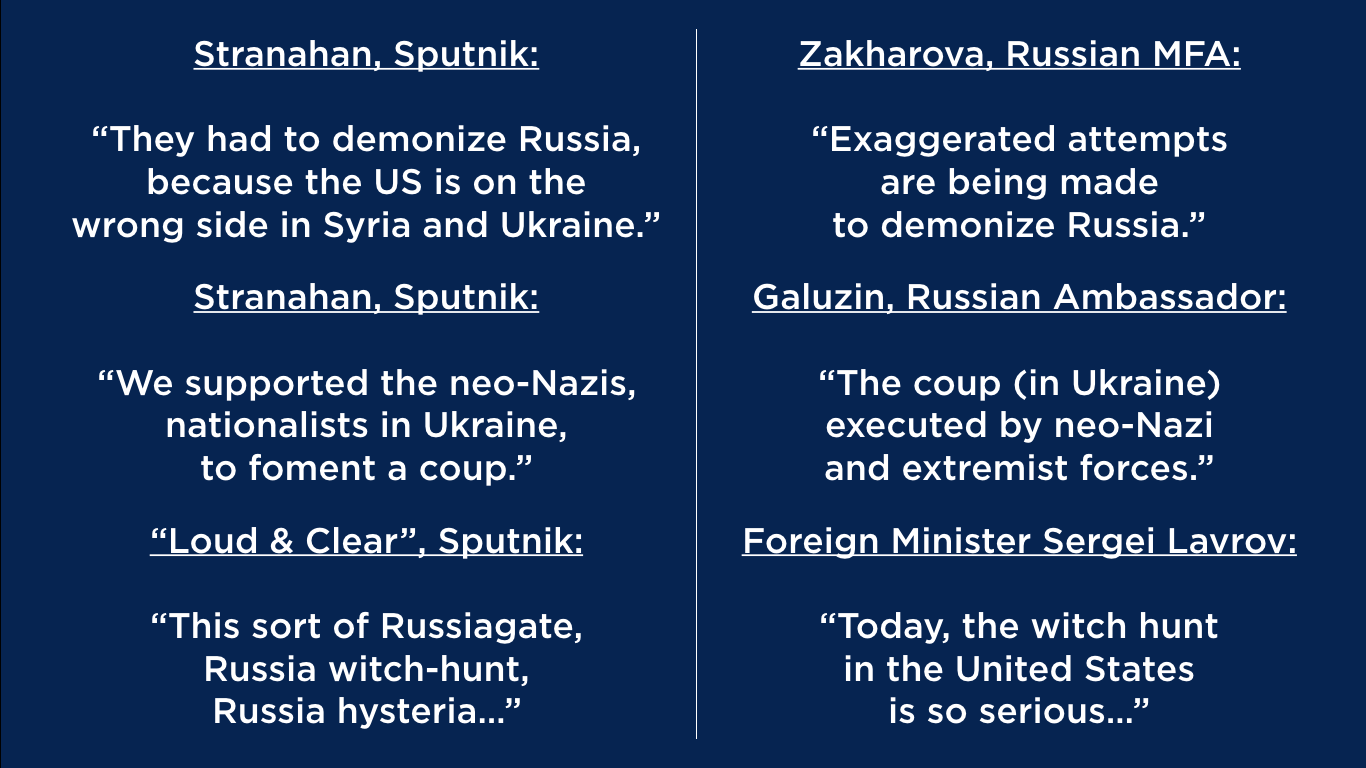

Sputnik radio shows in late December 2017 also referred to the Special Prosecutor’s investigation into Russian interference in the U.S. election as a “witch hunt,” termed the 2014 revolution in Ukraine a “coup” fomented by “neo-Nazis,” and accused the West in general, and the U.S. in particular, of trying to “demonize” Russia.

Almost identical comments have been repeatedly made by Russian government officials, including Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, Foreign Ministry Spokeswoman Maria Zakharova, and Ambassador to Indonesia Mikhail Galuzin.

The comments aired on Sputnik may well have reflected the Sputnik presenters’ private convictions; this does not lessen the fact that, if they had been journalists, they would have been obliged to reflect opinions which criticized Russia as well.

In these radio broadcasts, Sputnik’s presenters effectively acted as advocates for the positions of the Russian government which paid them.

Time and again, on a range of issues, Sputnik’s coverage has served to defend the Kremlin against charges of potential crimes, such as the shooting down of Malaysian Airlines flight MH17 over Ukraine in July 2014, the bombing of hospitals in Aleppo in the second half of 2016, and the poisoning of former spy Sergei Skripal in March 2018.

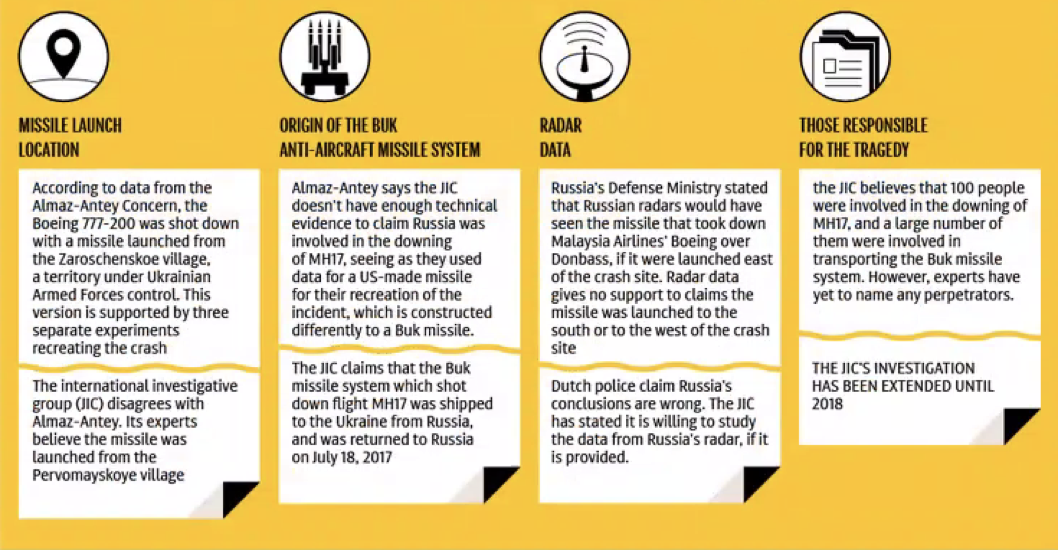

For example, an infographic attached to various Sputnik articles on MH17 systematically placed the word of Russian state-run arms manufacturer Almaz-Antey, which produced the missile in question, over the findings of the Joint Investigation Team (JIT), an international criminal investigation which concluded that the missile was brought into Ukraine from Russia.

Sputnik’s graphic portrayed the JIT’s conclusions as hypotheses, using words such as “believe,” “claims” and “disagrees with Almaz-Antey.” It gave column space to Almaz-Antey’s reasoning and alleged evidence, without mentioning any of the evidence on which the JIT based its conclusion. An accompanying article stated that Almaz-Antey had “confirmed that the Boeing was shot down from territory controlled by Ukrainian forces,” as if Almaz-Antey’s allegation was irrefutable.

This is a systematically biased use of language which appears aimed at undermining the JIT at Almaz-Antey’s expense.

On Aleppo, meanwhile, Sputnik published a series of attacks on key witnesses to the suffering of civilians during the siege. The most notable targets were the “White Helmets” rescue group, and a young girl called Bana Alabed, who tweeted about daily life under siege. Both were the subjects of repeated Russian attacks, which appeared aimed at discrediting them as witnesses; Sputnik played a supporting role in the campaign.

Sputnik’s stock language on Bana, repeated verbatim in two articles, betrayed an immediate bias, using the indeterminate phrase “many have called…” without naming its sources:

“Many have called the authenticity of the account into question, pointing to videos where Bana appears to be reading from a prompt. It is also unclear whether Bana’s posts are genuine, since any user, anywhere in the world can post from the account, as long as they have the password.”

Sputnik’s very first attack on the White Helmets quoted an article written by Syrian regime supporter Vanessa Beeley for online site 21st Century Wire. This is a conspiracy site which claims that the attacks on the World Trade Center in New York on September 11, 2001, were a U.S. government “false flag” operation.

Sputnik’s choice to quote an article from a 9/11 conspiracy site as its sole source for the attack on the White Helmets appears to confirm its desire to promote Kremlin narratives over the need for credible sources.

The same Sputnik article called the White Helmets “Soros sponsored,” a reference to the Hungarian billionaire who has become a hate figure for the Kremlin and far right for his support for pro-democracy movements.

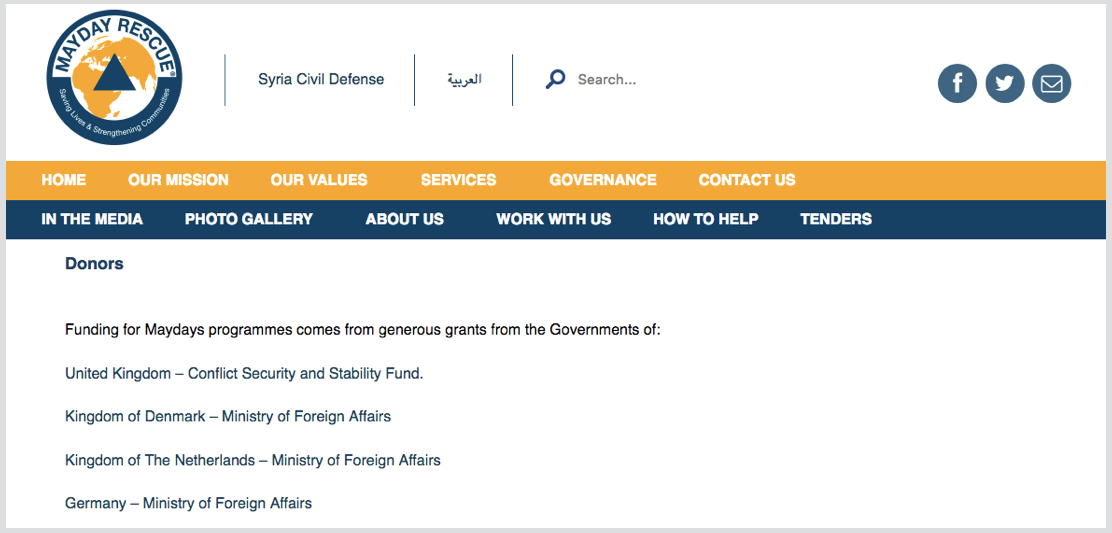

According to the website of Mayday Rescue, which founded the White Helmets, this is incorrect: its funders are the British, Danish, Dutch and German Foreign Ministries. It is unclear whether Sputnik’s error was deliberate, or another failure to perform basic due diligence.

It is instructive to contrast Sputnik’s approach with that of fact-checking website Snopes, which investigated Beeley’s oft-repeated claim that the White Helmets had terrorist ties, and concluded, “To date, we have found no credible evidence or reports that link the White Helmets organization with terrorism.”

Sputnik was also outspoken in its attacks on the British government in 2018, after UK Prime Minister Theresa May accused the Russian state of an “unlawful use of force” in the Skripal poisoning case.

Sputnik articles on the Skripal case made the editorial claims that, among others, May “rushed to” her conclusion, that Britain “failed to provide tangible evidence” for its accusations, that “many people are starting to wonder” about the UK’s claims (note the similarity to the attack on Bana), and that the West expelled Russian diplomats “without providing any evidence” — despite the fact that the British Foreign Office tweeted and published its reasoning, identified the nerve agent involved, and had the identification confirmed by the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW).

Sputnik published standalone interviews on the Skripal case with commentators including Putin’s French biographer, the Russian Presidential Envoy to the Volga Federal District, and an “internet author and researcher” called Joe Quinn.

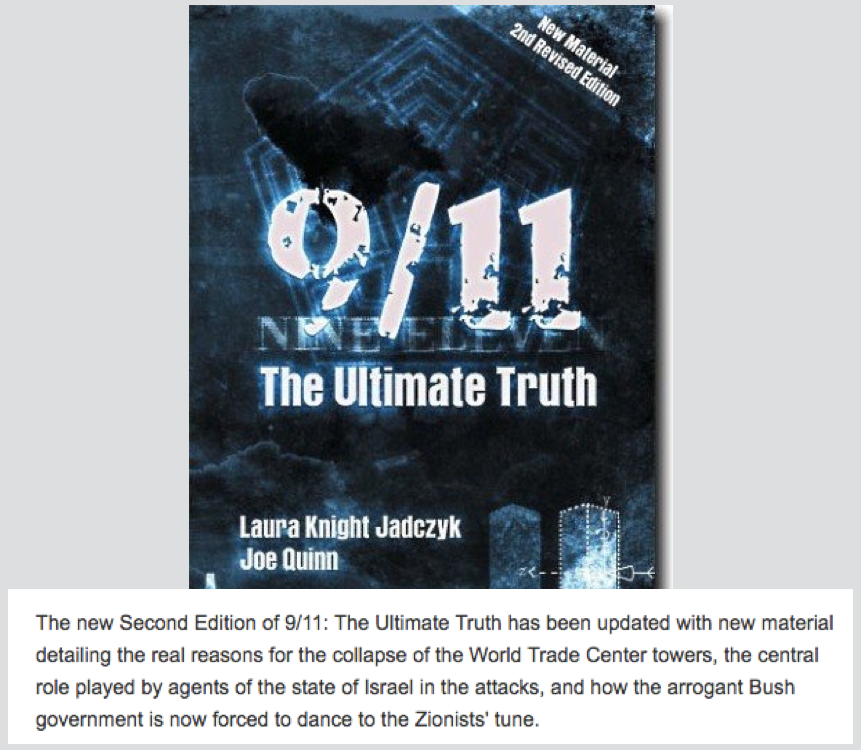

The Quinn in question appears to be the co-author of a book which claims that a “central role” in the 9/11 attacks was “played by agents of the state of Israel,” and that the “arrogant Bush government is now forced to dance to the Zionists’ tune.”

The same Quinn is a regular contributor to conspiracy site sott.net, a leading amplifier of pro-Kremlin and anti-Western narratives. He has his own website, which is routinely anti-U.S. and anti-UK, and features an entire section, critical of Israel, dedicated to “Jews.”

None of these interviewees can be viewed as an impartial observer; given his background in conspiracy theories, Quinn cannot even be seen as a credible one.

Sputnik’s coverage amplified the views of these commentators without making any attempt to challenge them in the interest of journalistic balance. This appears, yet again, to show a policy of amplifying voices which support the Kremlin or attack its critics.

Election Interference

The efforts described above can be seen as primarily defensive, aimed at supporting the Russian government. A separate strand of Sputnik’s work, however, appears aggressive, aimed at interfering in the democratic processes of countries critical of the Kremlin.

To do this, Sputnik uses the same techniques, giving copious, one-sided coverage to incidents and commentators which present the target in a bad light, regardless of their credibility.

Of course, some outlets in the target countries do the same thing; that is the nature of journalism. However, Sputnik is not a commercial journalism outlet. As we have seen, it is a state-owned communications agency whose task is to “secure the national interests” of that state.

Its partisan coverage of democratic processes in other countries, in the language of those countries, therefore appears to be an attempt by the Russian state at interference.

Anyone but Clinton

The most obvious example is Sputnik’s coverage of the 2016 presidential race in the United States. This was routinely hostile towards Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton, especially after audio tapes which showed Republican rival Donald Trump making obscene boasts about women were leaked on October 7, 2016.

In the following days, Sputnik ran a series of opinion pieces arguing that a Clinton presidency would lead to World War Three — a literally apocalyptic warning. Each opinion piece came with a disclaimer, but they were so consistent in tone, so close together in time, and so lacking in countervailing voices, that they effectively constituted an editorial line.

The articles included claims that “for anyone interested in peace, stability, and the defeat of terrorism across the world, the prospect of Hillary Clinton in the White House is a chilling prospect indeed;” that Clinton is “pushing the U.S. towards confrontation with Russia without scruple;” and that the “prospect of having axis of evil practitioner Hillary Clinton with her fingers on the nuclear button must be seen as the most life-and-death issue in this whole circus.”

Over the same one week period, from October 7–14, 2016, one Sputnik articlereported on accusations of “horrific” behavior by Clinton against a woman who had accused former President Bill Clinton of rape. Another called Clinton a “clear and present danger to world peace.” Neither gave Clinton the right to reply.

And at least five articles over the period focused on the release, by Wikileaks, of emails stolen from Clinton campaign manager John Podesta by Russian hackers, in Russia’s most damaging influence operation of the campaign.

Strikingly, one of the Sputnik pieces claimed, “Podesta asserts that the emails released by the prominent whistleblower are riddled with fakes and forgeries,” citing a tweet as proof. In fact, Podesta made no such claim; instead, it was tweeted by security commentator Malcom Nance.

It is possible that this was sheer incompetence on Sputnik’s part; as we have seen, its editorial standards do not reflect the need for accuracy embodied in the style guide. However, it is equally possible that the misattribution to Podesta was deliberate, and designed to discredit Clinton and her campaign.

Negative coverage of Clinton was a feature of Sputnik’s output throughout 2016. Earlier articles, for example, headlined her as “trigger happy” (a comment Sputnik admitted it drew from her presidential rival, Trump), a “warmonger” and a threat of “nuclear war with Russia or China.”

The latter pieces covered, respectively, an anti-Clinton article by Jeffrey Sachs, and an interview with former Republican adviser James George Jatras, who has accused Britain of interfering in U.S. democracy, while calling the mass of evidence of Russian interference “bogus.”

Again, Sputnik gave these Clinton critiques extensive coverage, without providing any meaningful coverage of the Clinton campaign’s point of view — a glaring violation of basic journalistic standards.

It is worth questioning how much impact these blatantly one-sided pieces had; the answer is unclear. On one occasion, however, a piece published by Sputnik achieved significant reach, and influenced the election debate.

On September 12, 2016, Sputnik published an extensive piece by U.S. researcher Dr. Robert Epstein, arguing that Google was rigging its autocomplete results in favor of Clinton.

Headlined “SPUTNIK EXCLUSIVE: Research proves Google manipulates millions to favor Clinton,” the piece claimed that the search engine “withholds negative search terms for Mrs. Clinton even when such terms show high popularity in Trends,” and that “whatever autocomplete was in the beginning, its main function may now be to manipulate.”

As @DFRLab has already written, the premise of the article was flawed; the theory of rigged auto-complete suggestions had been debunked three months before. Epstein wrote in a subsequent tweet that he had originally pitched the piece to Politico, but that Politico “mysteriously killed” it; in his article, he noted that he gave it to Sputnik “because Sputnik agreed to publish it in unedited form in order to preserve the article’s accuracy.”

Despite its lack of credibility, the Sputnik article was picked up by conservative U.S. media, including Breitbart, which attributed it to Sputnik.

On September 29, 2016, in a prepared speech, Trump accused Google of “suppressing” bad news about Clinton. The likelihood is that his campaign took the allegation from conservative sites; but those conservative sites took it from Sputnik. In this case, therefore, Sputnik’s choice to run a questionable article on an already-debunked theme gave one candidate ammunition to attack the other.

Thus, overall, Sputnik’s coverage of Clinton was routinely hostile, frequently one-sided, and sometimes incorrect, but uncorrected. This bias was so systematic that it can only realistically have been the result of a deliberate choice to undermine Clinton and attack her campaign.

Britain’s Votes

Similar bias can be observed in Sputnik’s coverage of events in the United Kingdom, especially the Brexit referendum of June 2016.

Sputnik opinion pieces give a flavor of the coverage. As before, they often came with disclaimers, but were so consistently one-sided that they effectively constituted an editorial policy.

In the case of Brexit, Sputnik appeared to have given free rein to commentaries which cast the European Union in a negative light. For example, blogs in May 2016 called EU leaders “power-grubbing opportunists,” characterized the Leave campaign as an attempt to “liberate Britain from globalist inspired tyranny,” and compared the EU and NATO with the fascist Axis of World War Two.

Sputnik’s analytical content was equally one-sided. For example, articles in the two months before the referendum alleged that criticism of Russia was being “used to force Britain [to] stay,” and that an EU trade deal with Canada was “set to undermine democracy and destroy basic rights of workers.”

One piece attacked the economists who warned of a Brexit-driven economic downturn, saying that they were “members of the Royal Economic Society and the Society of Business Economists, which implies their tighter affiliation with the narrow interests falling in line with the current political agenda prevailing on Downing Street.”

As in the case of the UK election, these pieces were so one-sided that they effectively constituted an editorial policy of promoting Brexit, and attacking the EU and the Remain camp.

Of course, some commercial UK outlets made the editorial choice to be equally outspoken in favor of Brexit; but Sputnik is not a commercial concern. It is a Russian state outlet, whose editorial line on key issues is indistinguishable from that of the Russian government. Its one-sided editorial stance therefore resembles an attempted influence campaign.

Conclusion

This is only a snapshot of Sputnik’s output, but it is sufficient to illustrate the overall trend.

Sputnik’s behavior in its reporting is consistent with the documents which created the outlet. It praises Russian weaponry, while criticizing Western models; it boosts Russian tourist resorts and events.

On issues of foreign policy, it routinely endorses the Kremlin’s view of events, attacks Kremlin critics and amplifies speakers who do the same, regardless of their credibility (or lack thereof). It also covers domestic politics in target countries in a way which targets Kremlin critics and maximizes division.

None of this is consistent with the demands of balanced and independent journalism. Sputnik was created by the Russian state to “secure the national interests of the Russian Federation;” its publications are fully in line with that mandate.

By Ben Nimmo, for DFRLab

Ben Nimmo is Senior Fellow for Information Defense at the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab (@DFRLab).

Follow along for more in-depth analysis from #DigitalSherlocks.