By Ben Nimmo, for DFRLab

Pro-Kremlin, pro-Assad, and far right online communities align to claim chemical weapons attack was a “false flag”

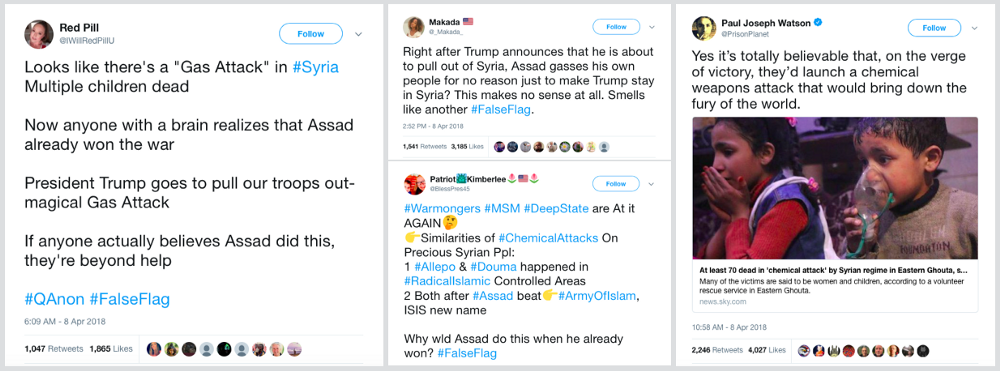

Within hours of the reported gas attack on civilians in the Syrian rebel held area of Douma on April 8, claims began circulating on social media that the attack was a “false flag” staged by the rebels, or perhaps the West.

Accusations of such deception regularly follow major incidents. Since they were made well before the evidence could be analyzed, it is not possible to assess their claims directly. What was of interest, in this case, was the way in which the claims were advanced by two main groups — supporters of the Kremlin and Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and supporters of the far right on either side of the Atlantic.

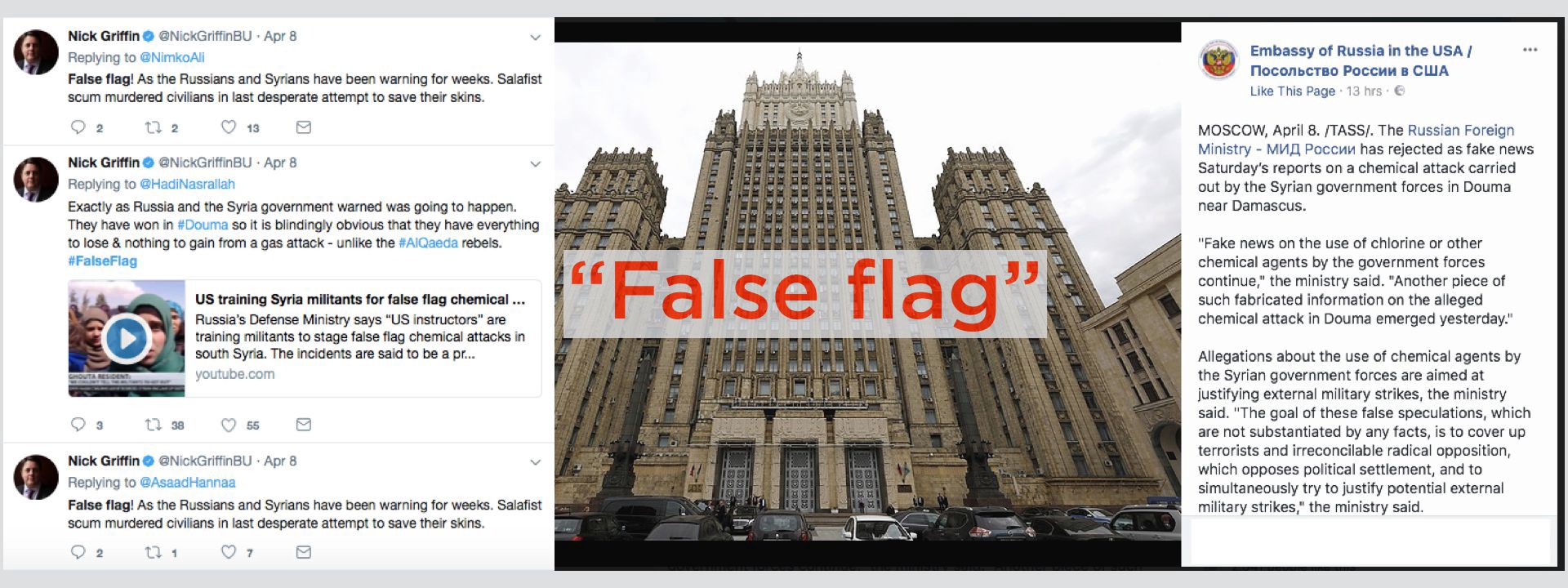

Russian and pro-Russian claims

The Russian government itself took the lead in the “false flag” claim, although it did not use that exact term. The Russian Foreign Ministry, in a Russian-language post, called reports of the attack “fabricated” and a “dangerous provocation.” A Facebook post from the Russian Embassy in the United States called the attack “fake news” and “fabricated information.”

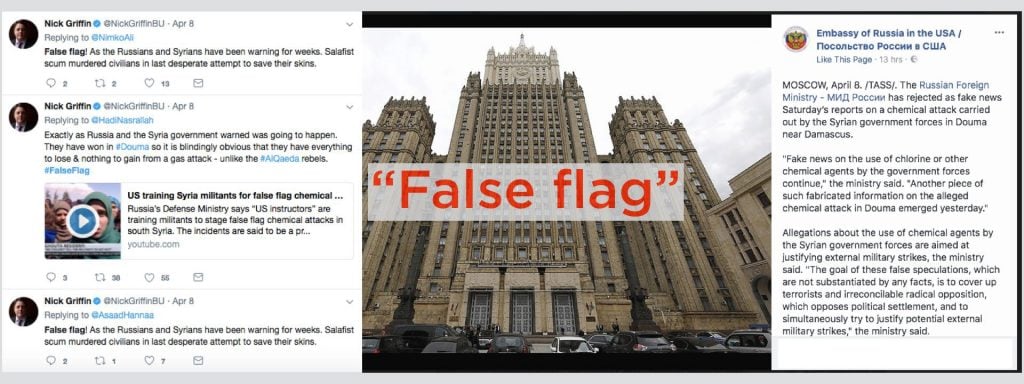

Pro-Kremlin Twitter users made the same claim. One of the most active was @Ian56789, which @DFRLab and other researchers have already identified as possibly linked to the “troll factory” in St. Petersburg.

@Ian56789’s primary focus was — and remains — supporting the Kremlin and attacking its critics. The same account claimed that the sarin attack on civilians in Syria in April 2017 and the shooting down of Malaysian Airlines flight MH17 over Ukraine in July 2014 were also both false flag attacks.

The user was wrong in both cases: a United Nations probe found the forces of President Bashar al-Assad guilty of the sarin attack, while an independent, international criminal probe found that the weapon which downed MH17 came from Russia.

Other pro-Kremlin accounts also advanced the “false flag” narrative; as @DFRLab has already reported, the Kremlin has repeatedly accused the Syrian opposition in general, and the “White Helmets” rescue group in particular, of “provocations” of this nature.

Given the Kremlin’s policy of supporting Assad, such posts are understandable. However, these accounts have a poor record of accuracy on “false flag” claims, as the 2017 sarin attack and the MH17 downing show. Their activity should therefore be taken as an attempt to exculpate Assad before the evidence is reviewed, rather than an evidence-based analysis.

Assad supporters

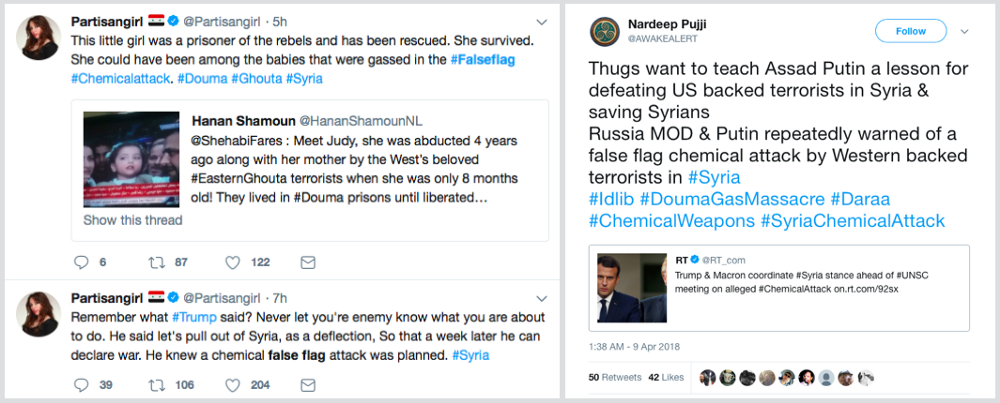

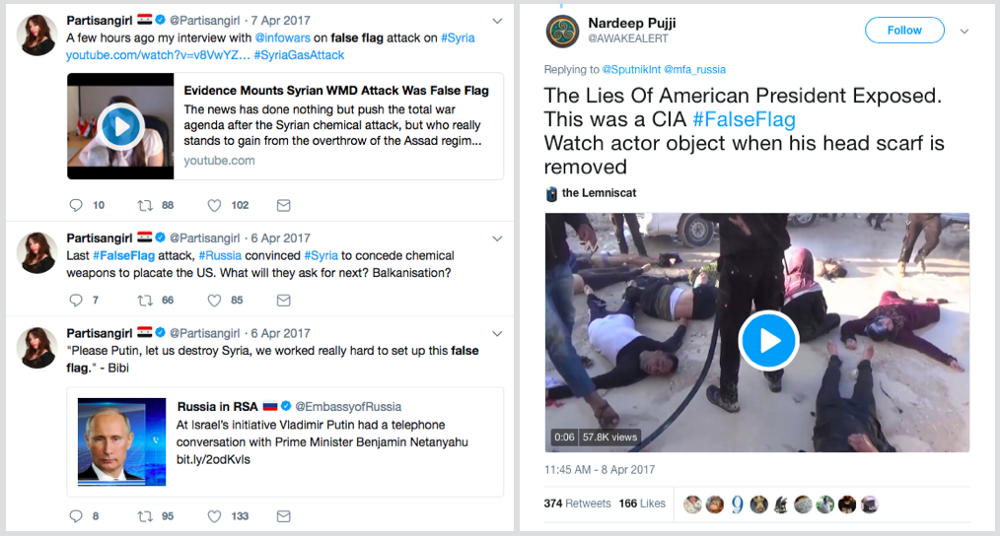

Supporters of Assad also advanced the claim that the attack was a false flag. They included @Partisangirl and @AWAKEALERT, who are among the Syrian president’s most active and influential supporters online.

Both accounts made similar claims after the April 2017 sarin attack, which was later found to have been conducted by Assad’s forces.

These accounts are closer to Syria than the pro-Kremlin ones, and post about its conflicts more regularly. However, the speed at which they made the claim, and their track record of inaccurate analyses, suggest that, again, the claim of a false flag was not backed up by substantial, or any, evidence.

Far right voices

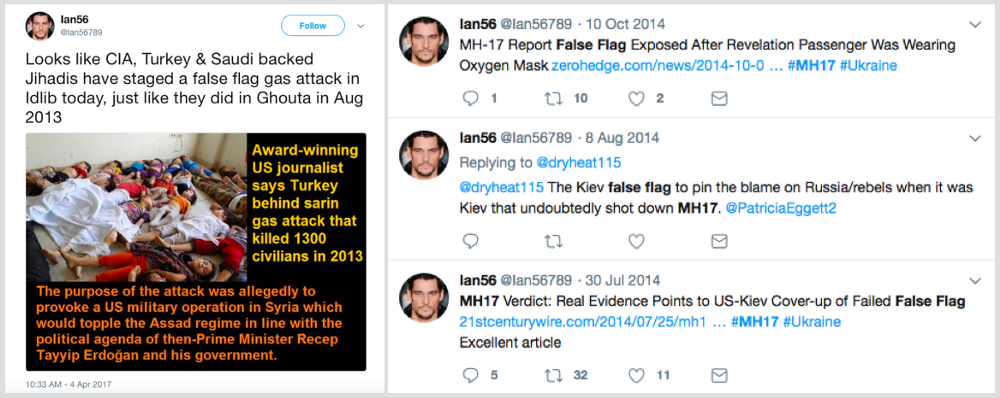

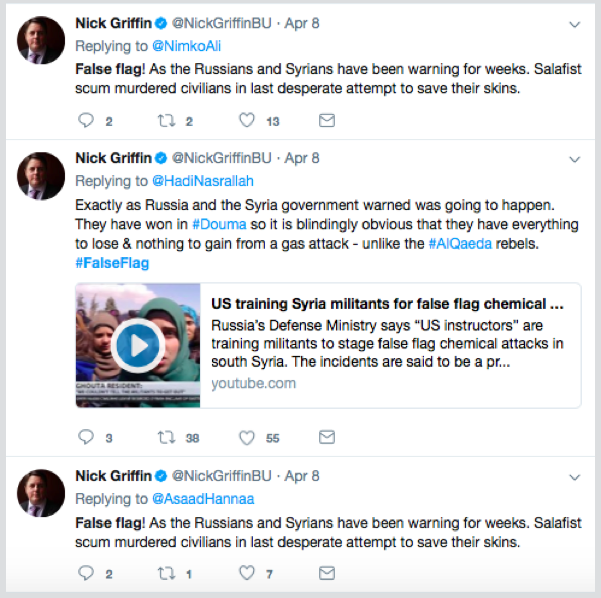

The claim of a “false flag” attack also circulated in far-right and conspiratorially-minded circles in the West. British nationalist Nick Griffin tweeted it repeatedly, blaming the attack on “Salafist scum”.

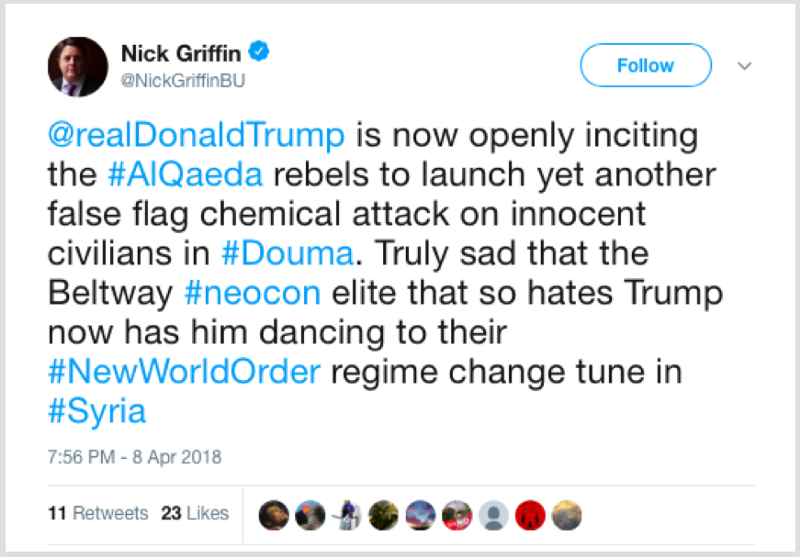

Griffin focused particular ire on United States President Donald Trump, who tweeted that “Animal Assad” would pay a “big price” for the attack. Griffin blamed Trump’s tone on the foreign policy establishment in Washington, D.C., which he portrayed as part of a “New World Order” plot, referencing a conspiracy theory popular on the far right.

Alex Jones, the host of conspiratorially-angled site Infowars, took a similar line, linking the apparent chemical attack to Trump’s surprise announcement, the week before, that the U.S. would pull its troops out of Syria.

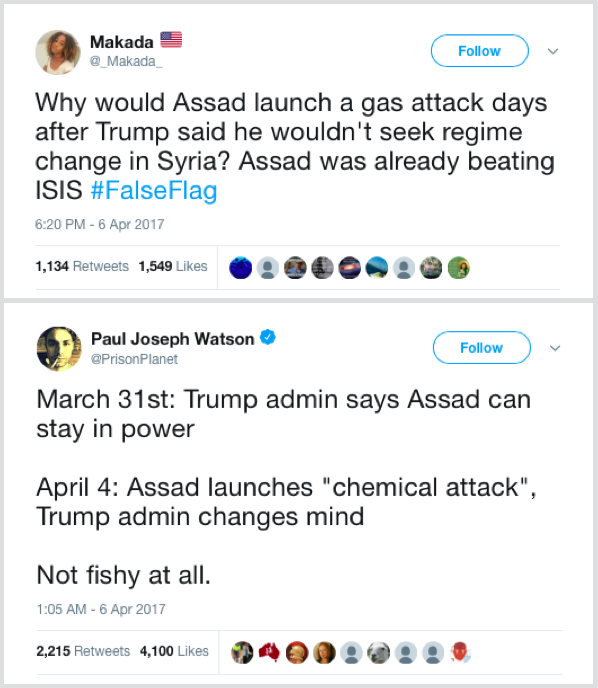

Self-styled “nationalist, conservative” account @_makada_ argued that it would have been illogical for Assad to launch a chemical weapons attack, as did a number of other accounts.

Some of the above accounts made a similar case after the 2017 sarin attack, arguing, or implying, that Assad had nothing to gain from the strikes, since he was already in an advantageous position.

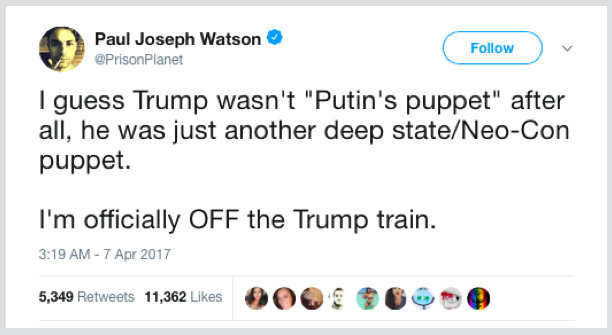

The motivation of these accounts appeared more mixed. The primary focus of criticism seemed to be the Western policy elite, often referred to as “neocons” (a pejorative common to far-right and pro-Kremlin users). These are the elites whom Trump’s support base expected him to sideline; after his administration launched air strikes against Syria in response to the April 2017 sarin attack, a number of his most ardent followers from outward end of the political spectrum turned on him.

Their primary purpose seems to be to curb what they see as the power of the Western establishment.

Conclusion

The reaction to the reported chemical attack in Syria exemplified the ideological intersection between geopolitics and national politics.

The reports were quickly dismissed as “fake news” and “false flag” attacks by supporters of the Kremlin and President Assad. Their concern appeared primarily geopolitical: staving off potential Western criticism or punitive measures by dismissing the claims against their principals.

The same “false flag” dismissal was used by far-right and conspiratorial users, but this appeared to have stemmed from primarily domestic reasoning. Rather than defending the Russian or Syrian regimes, the main aim appeared to have been to attack Western ones, portraying them as reckless, militaristic “neocon” elites, divorced from the democratic processes of government.

The reaction to the Syrian attack therefore illustrated how, and why, these separate groups promote the same messages. Their purposes are different; however, their target — Western governments and foreign policies — is the same.

By Ben Nimmo, for DFRLab

Ben Nimmo is Senior Fellow for Information Defense at the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab (@DFRLab).