By Ben Dubow, for CEPA

China and Russia employ two vastly different approaches to the deployment of information for domestic control and international influence.

Last year, Russia’s third-biggest television channel aired the names of all the soldiers killed during World War II. Showing 75 names every minute of every day, the full list required 2.5 months to run through, ending on Victory Day, May 9.

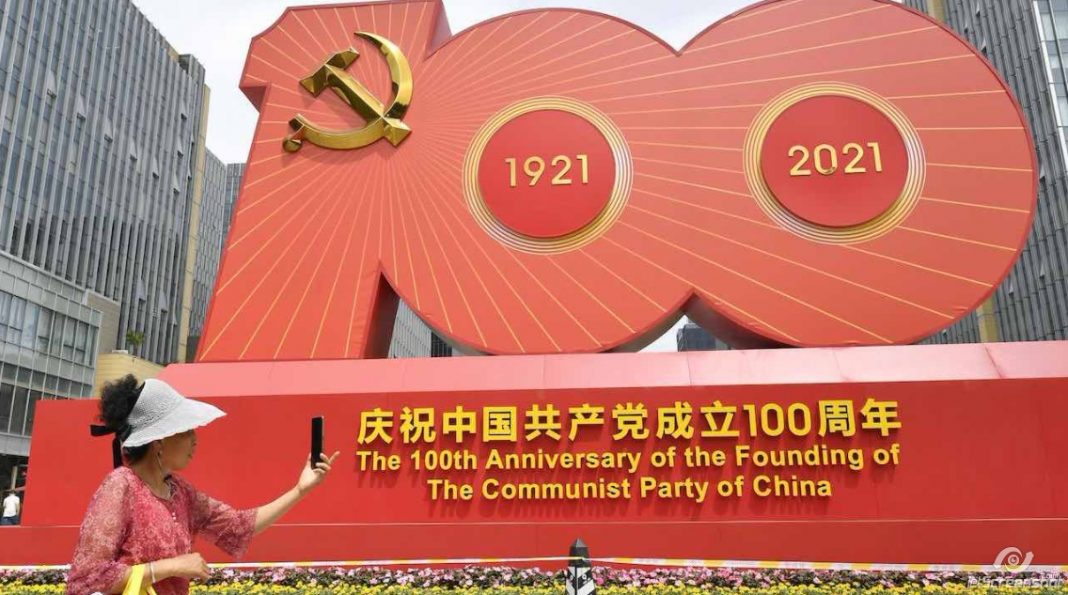

On July 1, 2021, the Chinese Communist Party commemorated its 100th anniversary, with every media outlet in the country spending months promoting a celebration including parades, performances, and much more. The two major commemorations provide a stark contrast, and illuminate where the two authoritarian states struggle, and where they thrive, in their approach to informational control.

Among Vladimir Putin’s top priorities in his first years, was the subjugation of Russian media to the state. Rather than perform the sort of seizures associated with revolutionary regimes, Putin’s ministers orchestrated a series of mergers, acquisitions, and forced debt repayments to give state-owned enterprises; Putin’s allies and government agencies controlling stakes in leading TV stations. When newspapers or broadcasters stepped out of line, their regime-aligned financiers would push out the old managers. The distributed nature of Russian media — developing as independent enterprises rather than by government diktat — allowed a competitive, if politically neutered, media environment to flourish. News channels, in fierce competition for attention, became hotbeds of conspiracies and sensationalism, often focused on foreign enemies.

The embrace of conspiracism would be crucial to Russian success on social media, which rewarded outrageous content over the staid material produced in the West. While much coverage has focused on Russian overperformance abroad, there was no guarantee that the government would dominate Russian-language social media, especially given the prominence of American platforms such as YouTube, Instagram, and Livejournal. But in the original analysis for this piece of 1.5m social media posts targeting a Russian audience, we found that 77% of all engagements (likes, shares, comments) accrue to outlets owned by the Russian government, 10% to National Media Group, owned by Putin ally Yuri Kovalchuk, and 5% to the pro-government newspaper Komsomolskaya Pravda. Novaya Gazeta, the leading opposition outlet, garners 2% of engagements.

As the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II approached, media in Russia could be trusted to provide an outpouring of patriotic material. This was not only politically astute but also good business: the defeat of the Nazis is the historical event in which Russians take most pride in, and the collapse of the Soviet Union the one for which they feel the most shame. Media owned directly or indirectly by the Russian government published over 3,300 pieces on the commemoration. From an article penned by Putin himself, blaming the West for the Molotov-Ribbentrop treaty, to shots of leading celebrities in Soviet uniforms, to marathons of Great Patriotic War films, Russia offered a variety, and depth of patriotic material to rival or surpass that of any country with a free press. The West, roiled by lockdowns and political infighting, offered little beyond perfunctory recognition of the anniversary, allowing Russian videos of military hardware, sky-filling fireworks, and Victory Day musicals to thrive.

In contrast to the bottom-up growth and competitive nature of Russian media, Chinese media functions as an organ of the state, with propaganda one of three main pillars of control of the CCP. National newspapers fill a few niches — Global Times as tabloid, Xinhua as newswire, etc. — and national television offers a variety of channels, though all under the auspices of the government’s Central China Television. Regional news and TV, however, are more uniform, often with single papers or TV channels for a province, or several all reporting to the same committee of the CCP. For instance, The Liaoning Daily is owned by the Propaganda Committee of the Liaoning Provincial Committee of the Communist Party. Shaanxi TV is owned by the Propaganda Committee of the Shaanxi Provincial Committee of the Communist Party. This makes Chinese domestic media more consistent, the corollary of which is that Chinese media is less varied and therefore less adaptable.

With the rise of the internet, China was able to outsource demand for entertainment to tens of millions of influencers, tightly policing content with armies of censors and bots. This helped local apps like Weibo and WeChat grow to a global scale and ensure that the CCP, along with influencers who tow the party line, was the only source for news for hundreds of millions of users. Lack of competition has helped Chinese digital media dominate at home, but has hampered its efforts abroad, where, as reported here last month, tiny rivals like Falun Gong-aligned Epoch Media run circles around the CCP’s propaganda behemoth.

The 100th anniversary of the CCP’s founding revealed the stark contrast between the party’s domestic success, and international failures. As in Russia, China produced a vast range of material to promote patriotic fervor, from musical spectaculars to concerts and celebrity poetry slams. The accompanying Weibo posts were among the most liked and shared anywhere online. In our original analysis, we found that the only non-CCP post over the past week, among the 10 most-liked in the world, was a New York Times Instagram post about Britney Spears. The other nine, accounting for 6m likes and 11m shares, all commemorate the 100th anniversary of the CCP’s founding. But that success belied the CCP’s weakness. While the 2,106 CCP publications we analyzed appeared on Twitter, YouTube, Facebook, Reddit, and VKontakte, over 99% of engagements (likes, shares, and comments) occurred on Weibo. A major success domestically, the celebration attracted little love abroad.

China and Russia employ two vastly different approaches to the deployment of information for domestic control and international influence. Ahead of major anniversaries celebrating national unity, both approaches exposed their respective state’s strengths and weaknesses. Russia’s competitive but pliant media produces content ripe for export, and crucial to influence abroad. China’s top-down approach is hugely effective for domestic goals, but hampers efforts internationally. In the run-up to the CCP’s 100th anniversary, both its accomplishments at home, and failures globally were on full display.

By Ben Dubow, for CEPA

Photo: Photo taken on June 30, 2021, shows an exhibit on display in Beijing to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party on July 1. Credit: Kyodo

Ben Dubow is CTO and founder of Omelas, a firm that provides data and analysis on how states manipulate the web to achieve their geopolitical goals and a Nonresident Fellow with the Democratic Resilience Program at the Center for European Policy Analysis. His research on Russian and Chinese online information operations has appeared in Reuters, The Moscow Times, Bloomberg, Roll Call, and has been targeted by Sputnik and RIA Novosti.

Europe’s Edge is an online journal covering crucial topics in the transatlantic policy debate. All opinions are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the position or views of the institutions they represent or the Center for European Policy Analysis.