“Poland is superior to Lithuania because of its long-lasting statehood and culture. Lithuania is superior to Poland thanks to its ties with the Americans and the Germans”.

Such statements, even if obviously untrue, are meant to create fertile ground for Russian influence operations targeting the Lithuanian and Polish infospheres.

Neighbours for hundreds of years, sometimes the best friends and sometimes foes or rivals, Poland and Lithuania have been in a close relationship for better and worse. Their relations have never been as close as they are now, sharing EU and NATO membership, trade ties and new bilateral energy links. Given geography and history, it comes as no surprise that this relationship has been of significant interest to the pro-Kremlin disinformation machine. A recent report by Info Ops Polska and Res Publica shows how difficult topics in relations between Poland and Lithuania are continuously and carefully exploited.

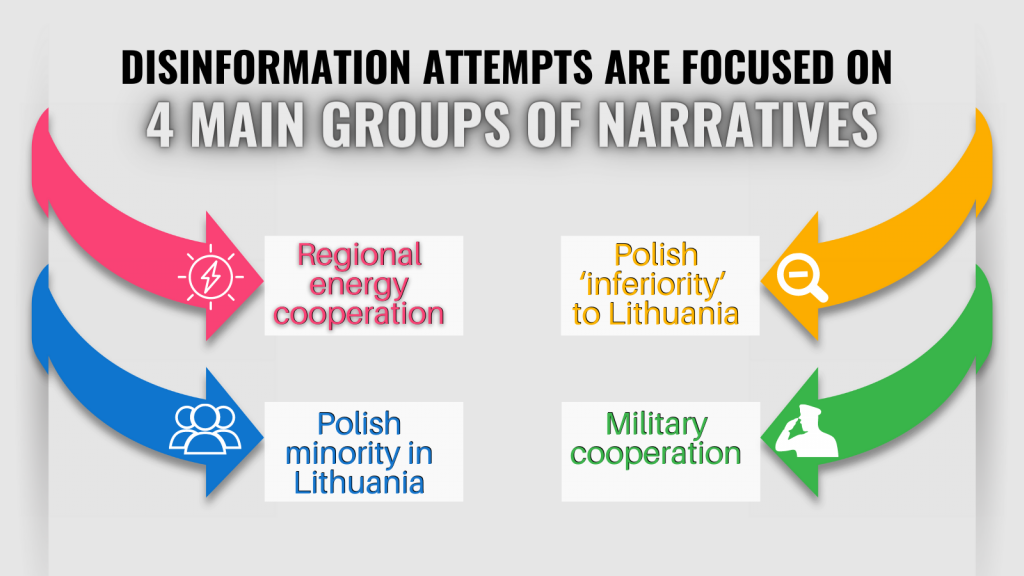

Disinformation attempts are focused on four main groups of narratives:

Regional energy cooperation

Pro-Kremlin outlets use energy politics and transit to influence Lithuanian (and Polish) perceptions regarding the Belarusian regime. After the rigged presidential elections in August 2020, pro-Kremlin and Belarusian state-controlled media alleged that if Belarus redirects its cargo flows away from Lithuanian ports, it would ruin the Lithuanian economy (see here for a case about this issue in our database). This was a reaction to the Lithuanian port of Klaipeda cutting off the Belarusian oil company BNK. Such a narrative is well-known to EUvsDisinfo: decisions not in favour of the Kremlin and its allies are pictured as harmful for the decision-maker only (examples here, here, here, and here). Reading that, a Polish recipient could get the impression that the Lithuanian economy is going down – a narrative designed especially for big Polish energy companies operating in Lithuania, such as Orlen.

Polish minority in Lithuania

Pro-Kremlin disinformation often exploits the issue of minorities to stir up tensions (examples include: Ukrainians in Poland, Russians in the Baltic states and other countries), and the case of the Polish minority in Lithuania is also used to advance the Kremlin’s interests in this regard.

Poland and Lithuania were joined in a union for hundreds of years, fighting together against the Teutonic Order, enjoying prosperity, fighting for independence in the 19th century uprisings. A good example of close Polish-Lithuanian ties is one of the most important Polish poems (dating back to 1811/1812), “Pan Tadeusz”. Written by Adam Mickiewicz (or Adomas Mickevičius in Lithuanian), it starts with the words ‘’Lithuania, My Homeland”.

But the common history is also full of difficult issues, especially in the 20th century. Therefore, it is not surprising that pro-Kremlin disinformation attempts to exploit them. On the one hand, it tries to play on historical sentiments by presenting Lithuanian nationhood nationality as artificial and contrasting it with the long history of Polish statehood, which supposedly evokes hatred from the Lithuanian side. On the other hand, it pictures the Polish minority as superior and at the same time threatened by the Lithuanian state or plays the card of alleged territorial claims that Poland would have to Lithuania if not for the Soviet past.

Polish ‘inferiority’ to Lithuania

Even though the narratives targeted at Poles living in Lithuania focus on alleged Polish superiority, another strand of pro-Kremlin disinformation contradicts it. It shows Lithuania as having the upper hand in the bilateral relations, due to dependence on the US and – sometimes – Germany. “Such a servile attitude lets Lithuania get away with its inherently anti-Polish (as well as anti-Semitic) stance and Poland can do nothing about it, since both countries are committed to common anti-Russian NATO objectives” – so is the narrative pointed out by the report. This kind of message aims at shaking the NATO alliance and portraying Poland as a weak state. And the fact that it is contradictory to other pro-Kremlin messages only helps fuel divisions. Consistency has never been the Kremlin’s strong suit.

Military cooperation

As NATO members on the Eastern flank of the Alliance, Poland and Lithuania are portrayed by pro-Kremlin disinformation as puppets of American policy, caring about the interests of their ‘’American master”, disregarding their own. Interestingly, as the report’s authors say, although “… both countries are seen as American puppets and provocateurs, Lithuania is in a way considered to be more malevolent and dangerous – since Lithuanian army is too small to win in a full-scale conflict [with] Belarus – and more broadly: Russia – it will drag into the war Poland and other NATO countries, causing disproportionately huge loses on all sides”.

Moreover, Poland and Lithuania are being accused of stirring up tensions in Belarus, rejecting partnership with Aleksandr Lukashenka’s regime.

Both narratives – about America and Belarus – are a very convenient pretext to claim that Poland and Lithuania are the sources of instability in the region. EUvsDisinfo database is full of other examples of other narratives of this sort (see examples here, here and here).

These narratives spread with different intensity, depending on what is going on in bilateral and international relations – but they never stop. The disinformation machine works constantly and adjusts its messages to the current situation. What is more, disinformation is only part of the whole set of efforts aimed at destabilizing the relations between Poland and Lithuania, consisting of cyber operations and provocations, to name but a few.

Laundering dirty narratives

How are the false and harmful messages spread? One of the common broadcasters in the Polish (dis)information sphere is Sputnik Polska. However, as we wrote numerous times before, once a manipulative or disinforming message appears on this website, it marks only the beginning of an information operation. Different actors and tools are applied to spread the messages as widely as possible and target the groups and individuals who provide the biggest chance of disseminating these messages effectively. The Info Ops Polska report confirms this pattern once again.

Specifically, the content from Sputnik is duplicated (with slight changes in some cases) and disseminated through different websites, the choice of which depends on the particular narrative. The next stage consists of spreading the same narratives via numerous blogs – this is the point where the content is adapted, so that it reflects the familiar style of a blogger. Nevertheless, the thrust of the pro-Kremlin narratives stays the same.

Next comes social media (chosen according to the message and the audience, its preferences, and vulnerabilities), especially closed groups devoted to specific topics – such as defence, energy or Poles in Lithuania. Another type of interference used by pro-Kremlin actors is engaging in discussions, both on internet fora and in the comments sections of different websites. They comment and put links to either the websites (used to disseminate Sputnik’s original message) or blogs. They do not usually link to the original Sputnik Polska article because hiding the connection to official pro-Kremlin Russian sources gives the message more credibility and makes it seem organic. This type of activity is usually carried out by fictious users who try to maintain the discussion, also by sending messages to individual users, including opinion leaders, in an attempt to spread the message further.

The targets are identified in accordance with their preferences and vulnerabilities, which pro-Kremlin actors have recognised and analysed in depth. If the operation succeeds, a disinformation message is then spread to the mainstream – in the social and traditional media. It also paves the way for sophisticated psychological operations and to many other gears from the Kremlin’s toolbox. The strategy described here is another example of the Kremlin’s broader strategy of ’’information laundering’’, described already by several studies in different contexts (see examples by NATO’s Stratcom Centre of Excellence, GMF, DFR Lab, Info Ops Polska and Avaaz). The idea is to cover the tracks of original pro-Kremlin message as much as possible in order to give it more legitimacy, by creating burner accounts, using ‘’independent’’, seemingly unrelated websites, changing the content posted by social media accounts.

To reach its goals, pro-Kremlin disinformation uses a combination of precise targeting and emotional narratives. The latter are deeply rooted in shared Polish-Lithuanian history and its – sometimes painful – effects. It is up to us, however, if we choose to appreciate what connects us or focus on what divides us.