By Mong Palatino, for Global Voices

Facebook is an important platform for sharing news and information online. But even the most savvy of internet users can have trouble separating the real from the fake on the platform.

New research by Global Voices shows that the “free” mobile version of Facebook, accessible free of charge for users in multiple developing countries, makes it even harder to assess the reliability of news articles than on the regular version of Facebook.

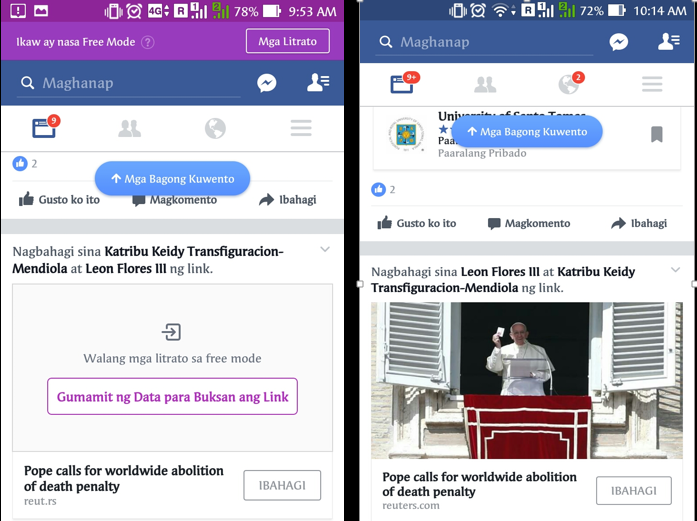

In Facebook’s effort to help introduce people in developing countries to the internet, the company has built a light-weight version of its website, which is offered alongside a handful of other sites and services offering things like news, weather and sports updates. This set of apps within an app is known as Free Basics.

In the light-weight version of Facebook offered via Free Basics, known in some countries as “Facebook Free”, users can connect with family and friends, chat using the Messenger app and upload or share content on Facebook without incurring data charges. But when it comes to news, they can only read article headlines and the captions of photos and videos. Unless they have a proper (and more expensive) data plan, the app does not allow them to read the news articles themselves.

In the current environment of hysteria over the prevalence of misinformation and “fake news” online, this limitation leaves users with limited budgets at a loss, giving them less access to useful information — and little capacity to determine whether the content is reliable or not. A user cannot see photos, videos, or the text of news articles from sites that are not included in the Free Basics package, which tend to be very few. To view this content, a user must pay data charges.

The Philippines had more than 47 million Facebook users in 2016, many of whom use Free Basics, which is provided in partnership with either Globe Telecommunications or Smart Communications.

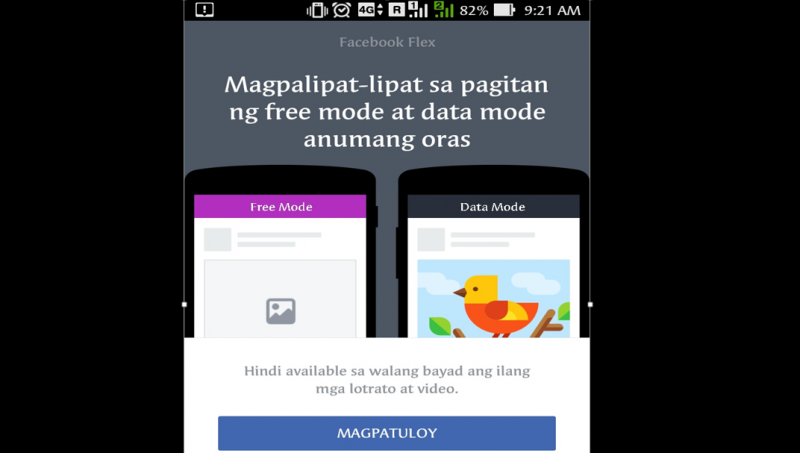

Below we see the difference between the Facebook Free timeline (left) and the regular Facebook interface:

“Walang mga litrato sa free mode, Gumamit ng Data para Buksan ang link” translates into “There are no photos in free mode, Use Data to open Link”.

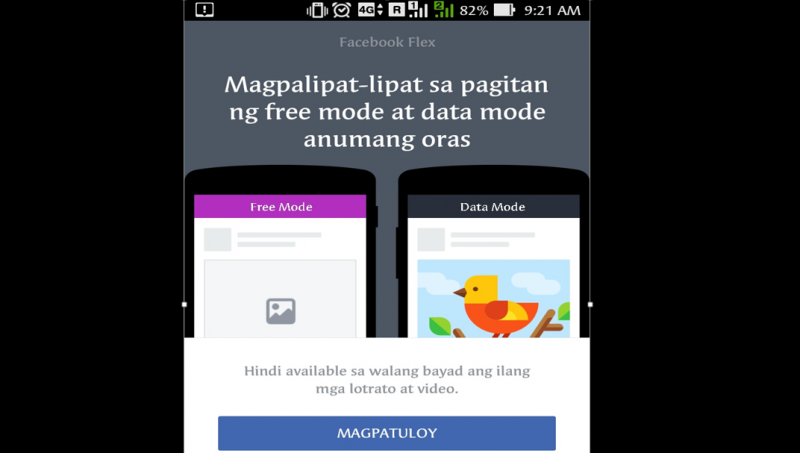

To switch from “free mode” (left) to “regular mode” (right), the user is notified that he or she must pay for data charges:

Main text: Use Data from Your Plan. You are leaving Facebook. Buy data from Globe in order to chat with friends, read article, and others. Screenshot by author

This is an easy option for those who can afford to pay the charges, but not for those who can’t. This is unfortunate for those who are using Free Basics because they can’t afford the full cost of connecting to the global Internet.

When installing Free Basics for the first time, the user is informed through the app’s terms and conditions that charges apply if photos, videos, and external links are opened on Facebook. A mobile user with a postpaid plan can simply agree to use his or her existing data plan for the extra charges, but a prepaid user has to pay for it in a store or a market offering a Globe or Smart load (known as top-up card in other countries). The majority of internet subscribers in the Philippines are prepaid users.

This is the relevant clause in the terms and conditions by Globe, one of the two major telcos in the Philippines:

You can now access a version of Facebook on your mobile phone without using your data allowance with Globe. However, if you leave this version of Facebook, or view content outside of Facebook, such as links to articles or external videos, then you might start using your data plan to see that content.

When ‘fake news’ meets ‘free’ Facebook

If Facebook Free is a user’s only source of news, chances are that he or she will encounter articles with dubious information and sourcing, but will not have the tools to verify them. Consider the examples below:

There is a risk of Facebook Free users promoting fake news content without immediately realizing it. Here is a headline that seems newsworthy from a news website with a name similar to Al Jazeera:

Of course, the website is not actually Al Jazeera, but a copycat. However, without associated images, satire websites can also be harder to detect.

Among those who shared these articles are friends (of the author) who are university-educated and have spoken quite critically about fake news. Facebook Free clearly makes it more difficult to determine whether a clickbait headline is a factual news article or something less reliable.

Even headlines of legitimate news websites can mislead Facebook Free users. Below we see a news headline dated March 31, 2017 about Donald Trump referring to the Philippines as a “terrorist nation”.

While a regular user would be able to see that he made this comment in August 2016, before being elected president, a Facebook Free user would have no such information and could easily be led to believe that this had happened in recent days.

Facebook Free provides easy ways to communicate and access information. But its strict limitations on access to the broader web, along with its omission of key fact indicators such as images, may ultimately disempower users by giving them incomplete — and sometimes completely inaccurate — information.

By Mong Palatino, for Global Voices