By Tommy Shane, for NiemanLab

“On Google, searching for ‘coronavirus facts’ gives you a full overview of official statistics and visualizations. That’s not the case for ‘coronavirus truth.’”

Ed. note: Here at Nieman Lab, we’re long-time fans of the work being done at First Draft, which is working to protect communities around the world from harmful information (sign up for its daily and weekly briefings). First Draft recently launched a publication, Footnotes: “A dedicated online space for people to publish new ideas, preliminary research findings, and innovative methodologies.” We’re happy to share some Footnotes stories with Lab readers. As First Draft executive director Claire Wardle writes, “If the agents of disinformation borrow tactics and techniques from each other, which they do, then so must we.”

When we think about disinformation, we tend to focus on narratives.

5G causes coronavirus. Bill Gates is trying to depopulate the planet. We’re being controlled by lizards.

But while narratives are concerning and compelling, there is another way of thinking about online disinformation. All narratives, no matter how bizarre, are an expression of something that underlies them: a way of knowing the world.

Contrary to claims that we live in a post-truth era, research suggests that people engaging with disinformation care deeply about the truth. William Dance, a disinformation researcher who specializes in linguistics, has found that people engaging with disinformation are more likely to use words related to the truth — “disingenuous,” “nonsense,” “false,” “charade,” “deception,” “concealed,” “disguised,” “hiding,” “show,” “find,” “reveals,” “exposes,” “uncovers.”

People engaging with false news stories are not disinterested in truth, but are hyper-concerned with it — especially the idea that it’s being hidden.

Because they can seem bizarre, misinformed narratives can sometimes lead others to assume their proponents are simply irrational or disinterested in truth. It can also distract from the ways of knowing that lead people to conspiracy narratives. Not everyone is interested in accounts of the world based on institutionalized processes and the perspectives of experts.

Some people may value different methods, rely on different evidence, value different qualifications, speak in different vernaculars, pursue different logics, and meet different needs. In the words of tech journalist and author Cory Doctorow, “We’re not living through a crisis about what is true, we’re living through a crisis about how we know whether something is true.” Part of that crisis stems from not understanding other ways that people know, and why.

The challenge we face is that we won’t know if trends exist, or if vulnerabilities are growing, unless we ask the right questions. What are the different ways people seek knowledge online? What assumptions underpin them? How are they changing? Are they being manipulated?

We also need to find out how to answer these questions. We need to find a route from the abstract questions of knowledge to the measurable traces of online behaviors.

During the pandemic, we’ve been experimenting with ways to do exactly that. In the midst of the pandemic, we looked at search-engine results using different keywords related to knowing about coronavirus: “facts” and “truth.”

On Google, searching for “coronavirus facts” gives you a full overview of official statistics and visualizations. That’s not the case for “coronavirus truth.” There you’ll get results referring to cover-ups and reports that China has questions to answer about the Wuhan lab — one of the major early conspiracy theories about the origin of the virus.

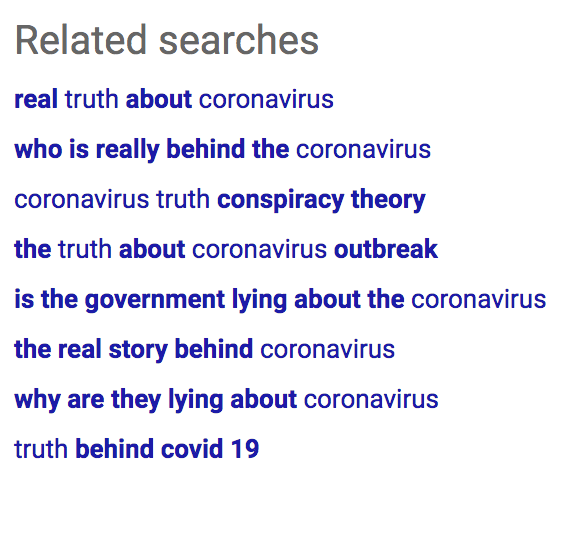

On Bing, we saw something similar but more pronounced. Where searches for “facts” yielded stories from official sources and fact checkers, one of the top results linked to “truth” is a website called The Dark Truth, which claims the coronavirus is a Chinese bioweapon. Its suggested stories for “coronavirus truth” prompted people to search for terms such as “the real truth about coronavirus,” “the truth behind the coronavirus,” “coronavirus truth hidden” and “coronavirus truth conspiracy theory.”

These results offer a glimpse into different ways of knowing online, and how platforms are responding with algorithms’ understanding (and production) of the different connotations of “facts” and “truth.”

Even though “facts” and “truth” might feel the same, they appear to engage with different ideas about information: for example, what we know versus what they’re not telling us; official statistics versus unofficial discovery.

When we’ve applied this same principle to the emerging threat of vaccine hesitancy, we see a similar pattern. “Vaccine facts” leads to official sources promoting pro-vaccine messages, while “vaccine truth” leads to anti-vaccination books and resources.

These results are snapshots of different knowledge-seeking behaviors, which consider a single entry point — “facts” and “truth.” But as this and other research suggests, there is much more to examine about ways of knowing, and how this plays into disinformation.

What might a framework of digital ways of knowing look like? Using facts and truth as illustrative concepts, we’ve proposed several dimensions (scale, process, causal logic, qualifications, method, tone and vernacular) as a starting point for considering different assumptions about what “knowing” might involve and to what narratives it might lead. Such an approach is designed to avoid the judgmental framing that conspiracy theories easily fall into. It is intended to show that certain ways of knowing, like lived experience, have their own validity that might not be recognized by the paradigm of fact checks.

Attention to ways of knowing as well as narratives can help us to ask different kinds of questions. How are ways of knowing changing? How might they be manipulated? How should reporters, educators and platforms respond?

If we fail to ask these questions, there is a risk that we won’t account for — or respect — the different assumptions people make when seeking knowledge. We may fail to speak across divides and ignore how other people’s needs from information can differ from our own.

We might also fail to understand how certain ways of knowing, such as media literacy, can be manipulated and weaponized. We know that some people are more likely to seek alternative, all-explaining narratives — those with low social status, victims of discrimination, or people who feel politically powerless. As well as witnessing the rise in 5G conspiracy theories, we may also be experiencing the rise of certain ways of knowing and their manipulation, especially in the context of a resistance to institutions and elites.

Donald Trump’s 2020 campaign has begun to engage with the idea of “truth over facts” with its campaign website thetruthoverfacts.com, which mocks a series of gaffes by Democratic candidate Joe Biden. Though the website is satirical, it primes the idea of the truth being something more fundamental — and Trumpian — than Biden’s misremembered facts.

At First Draft, we plan to develop techniques for monitoring and analyzing these behaviors in the coming months. We want to speak to others interested in this line of research as we experiment with new techniques. If you are interested in the study of online ways of knowing, or have something to tell us that we can use, we want to hear from you. Please comment below or get in touch on Twitter.

By Tommy Shane, for NiemanLab

Tommy Shane is First Draft’s head of policy and impact. A version of this story originally ran on Footnotes.