Allegations of planned political assassinations, lurid forgeries, false flag attacks, brazen online impersonations… the universe of Russian disinformation grows ever more grotesque.

A far-reaching and sophisticated Russian disinformation operation, most likely deriving from Russian intelligence, has been uncovered by the Atlantic Council’s DFRLab. The evidence suggests it ran for several years, with some content dating as far back as 2014.

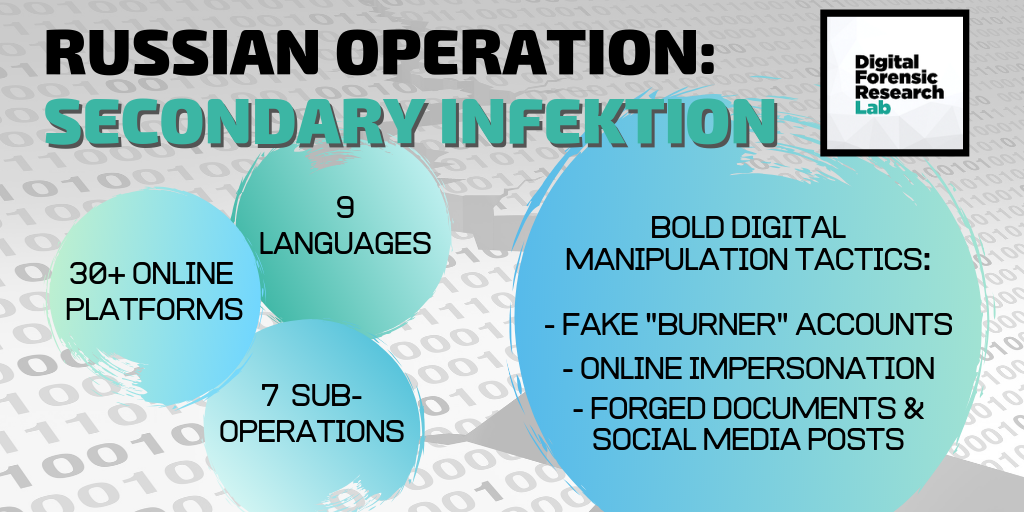

The DFRLab’s identification and analysis of the operation stemmed from Facebook’s takedown of 16 accounts, four pages, and one Instagram account in May 2019, which it assessed as a small network originating from Russia. Using these accounts, the DFRLab was able to unveil a much larger operation that utilised a variety of digital manipulation tactics – including fake accounts, social media impersonations, and forged documents – and played out across more than thirty online platforms in multiple languages.

The full report contains seven case studies focusing on different aspects of the operation: its most extreme lies, exploiting divisions in Ireland, fuelling anti-migrant sentiment in Germany, targeting Ukraine and the recent European elections, alleging a false flag attack in Venezuela, and amplifying pro-Kremlin foreign policy narratives.

Despite this multifaceted focus, the objective of the operation was consistent with the Kremlin’s usual disinformation efforts, aiming to undermine Western stability, interests, and unity both domestically and internationally. A variety of well-established pro-Kremlin topics and narratives were exploited to exacerbate tensions between NATO allies (especially between the US and European countries), stoke racial and political hatred along existing fault lines (namely in Northern Ireland), and fuel fears about migration (namely in Germany). At the same time, many stories centred on developments in Russia’s neighbourhood and international sphere of interest (e.g., Ukraine, Venezuela, Syria), and interpreted them through a distinctly pro-Kremlin lens.

This article summarises the key highlights of the report, focusing on the operational strategy and new tactics of this influence campaign. While its level of ambition was high, the impact was generally low, with the vast majority of stories failing to gain any significant traction on social media.

Crucially, however, this operation exemplifies just how assiduously the Kremlin and other malign actors are adapting their techniques of digital manipulation to circumvent the emerging countermeasures implemented by governments and online platforms. Disinformation poses an intractable challenge precisely because it functions like a virus, constantly evolving and mutating to develop resistance against attempts to eradicate it.

Information laundering 2.0: Strategy and tactics

Operation Secondary Infektion was so named for its strategic similarity to Operation Infektion, the notorious Soviet disinformation campaign that falsely accused the United States of developing and weaponising the AIDS virus. This scheme involved planting the fake story in international media to obscure its fraudulent origin and then “laundering” it through Soviet channels until it gained enough traction that it was picked up by mainstream media in the West and reported as fact.

Operation Secondary Infektion followed the same principle, but involved the planting of numerous false stories on a broad variety of topics. These false stories were often based on forged documents or other photoshopped content (for example, fake Twitter posts by prominent politicians) and published by fake accounts on mostly peripheral websites (but also on more prominent platforms, such as Medium). Notably, these accounts were characterised by very short lifespans, effectively functioning as “burner accounts” apparently created for the sole purpose of publishing a particular story. Their lack of history or other activity appears to have been an operational security tactic aimed at evading detection or attribution. In many cases, translations of the articles were also published in multiple languages on other sites.

Once published, these stories were then shared by a second set of inauthentic accounts on Facebook, which the company determined were run from Russia. In one notable case, a story based on a fake Tweet by US Senator Marco Rubio gained sufficient traction that it was picked up and “reported” by RT Deutsch. The article included the image of the fake Tweet, accompanied with the disclaimer that “Rubio may have been warned by Republican HQ to take the accusation back and not trigger a new diplomatic row between London and Washington, because the tweet of July 30 is no longer active.”

It is unclear whether RT knew that the Tweet was false. In any case, we know that RT treats facts as something to be loosely interpreted or molded to serve its agenda. When, on 19 June 2019, Marco Rubio tweeted that the screenshot was a fake, having been alerted to it by the DFRLab, RT added a evasive editor’s note to the original article: “Senator Rubio denies in a tweet from June 19, 2019, to have written the above Tweet from July 30, 2018.”

The fake Tweet and meme, accusing the UK’s intelligence gathering agency of planning to use deep fakes to support Democrats during the 2018 midterms. It was first posted to the website funnyjunk.com by a burner account that was created the same day, only posted the one item, and became immediately inactive. Source: funnyjunk.com/archive

The article by RT Deutsch that reported on the fake Tweet as though it were true. The title reads: US Senator Marco Rubio warns of election interference by Britain. Source: deutsch.rt.com

Replicating the playbook

The same operational template was followed in several other cases, focusing on politically polarizing issues as well as conspiracy theories with particular appeal to the far right. One case involved an especially audacious (and sloppy) forgery of a letter supposedly written by the Spanish Foreign Minister Josep Borrell – nominated just last week for the post of EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy – alleging that “radical opponents of Brexit” were planning to assassinate Boris Johnson to prevent him from becoming prime minister. The forgery was first posted on Facebook, and then followed by a Spanish-language article posted on several different sites. An English translation was subsequently published on Medium, which was shared on several online forums. Burner accounts were used across the board.

The Facebook post, made by an account belonging to the Russian operation, that shared the fake letter attributed to Josep Borrell (misspelled “Borrel”) under the letterhead of the Spanish Foreign Minister’s office. The comment on the right reads, “Radical Brexit opponents are preparing an assassination attempt on Boris Johnson.” Source: Facebook

Another case, this time targeting political divisions in Ireland, involved three false stories based on forged documents and social media posts attributed to senior politicians, as well as Facebook accounts that impersonated Irish citizens. Each story was planted and spread using the same 3-step playbook described above: 1) posting a forgery online, 2) amplifying it in different languages via numerous accounts created specifically for this purpose, and 3) boosting the content on Facebook.

In Germany, the operation aimed at exacerbating anti-immigration sentiment – a particularly hot-button issue in the country – and increasing tensions with key allies, including the US, Poland, and Turkey. The recent EU elections were also targeted, albeit to a lesser degree, in a campaign that pushed the familiar anti-EU narrative that “liberal forces” in the European Union were “launching a war against the right”. Again, fake “sources” were manufactured to support these claims, specifically a forged letter (in Swedish) allegedly written by an MEP, calling for “resolute and united” cooperation between European liberals and conservatives against the far right.

Takeaways

What is the common thread between these various elements of the operation, beyond the obvious goal to weaken the West? The DFRLab report assesses that the overarching goal of the operation was in fact the promotion of pro-Kremlin foreign policy narratives, an effort which began in 2014-2015 and primarily centred on negative messaging about Ukraine. This agenda later expanded to include Syria and Venezuela, along with the more targeted anti-Western campaigns detailed above. Indeed, this interplay between the Kremlin’s broader geopolitical interests and its persistent attacks on the West is a consistent feature of Russian disinformation, as the EUvsDisinfo database also shows.

Notably, the operation’s scope, sophistication, and complexity indicate a high degree of coordination, suggesting that it was run by a well-resourced, professional entity – most likely Russian intelligence. In addition, the DFRLab concludes that the primary reason the operation fell short of more mainstream penetration was because of its commitment to operational security – that is, prioritising secrecy over clicks.

But this lack of impact offers little reason to celebrate, for two reasons. First, it indicates that there are well-resourced actors out there – certainly Russia, and possibly others – who are actively devoting time and resources to sharpening their digital manipulation skills, specifically with an eye to improving their concealment. Just because this particular operation was intercepted doesn’t mean we’ll be so fortunate next time. Moreover, the perpetrators are undoubtedly already studying their mistakes and will be better prepared next time around. Second, it showcases the ongoing vulnerability of the internet and online platforms to disinformation. Bad actors will continue to find new ways to circumvent safeguards, and civil society and governments must be prepared to keep pace and look for adequate responses to new threats.

There is a common adage in the field of cybersecurity: hackers only need to get it right once, but we need to get it right 100% of the time. In other words, breaching a system requires finding only one weak point – but defending a system requires the elimination of all vulnerabilities. The same principle applies to disinformation: one successful disinformation campaign is all it takes to cause significant damage – to sway an election, cause a public health crisis, or incite public unrest or violence. By contrast, defending ourselves against such attacks is a full-time job that requires constant vigilance and adaptation to changes in the threat landscape.