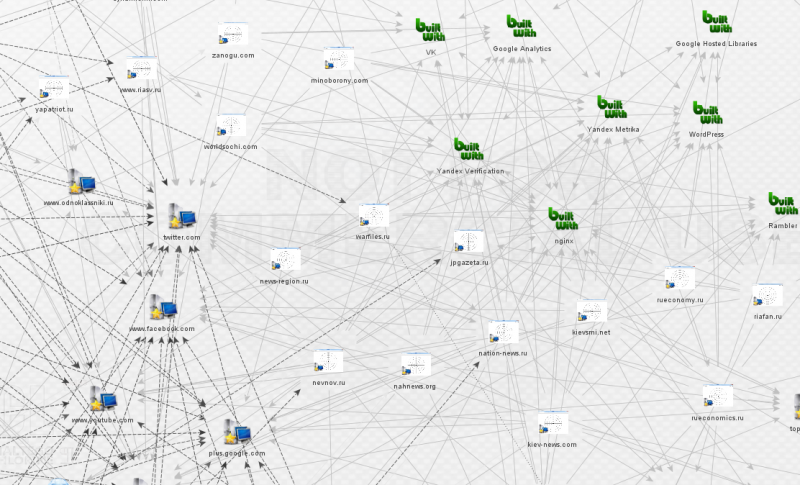

![Graph showing shared use of Google Analytics, server software, and social media by websites in the network. [Full size 1 2] Image by Lawrence Alexander.](http://www.stopfake.org/content/uploads/2015/07/WebsitesMaltego-800x485.png)

The site gives no credit or attribution for its design, and offers no indication as to who might be behind it. Intrigued by this anonymity, I used Maltego open-source intelligence software to gather any publicly-available information that might provide clues.

The Secrets of Google Analytics

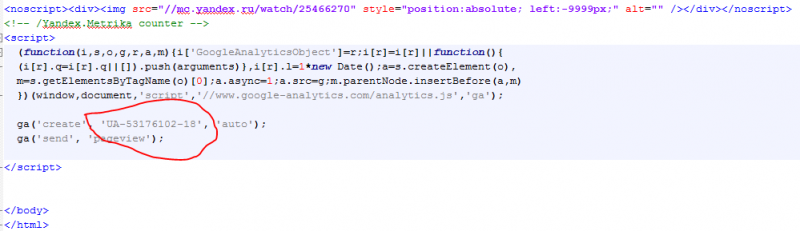

My use of Maltego revealed that the site was running Google Analytics, a commonly used online analytics tool that allows a website owner to gather statistics on visitors, such as their country, browser, and operating system. For convenience, multiple sites can be managed under a single Google analytics account. This account has a unique identifying “UA” number, contained in the Analytics script embedded in the website’s code. Google provides a detailed guide to the system’s structure.

Journalists and security experts have already raised the potential of this code to link anonymous websites to particular users.

The method was reported by Wired in 2011, and cited by FBI cyber crime expert Michael Bazzell in his book Open Source Intelligence Techniques. Several free services have sprung up that allow easy reverse searching of Google Analytics ID numbers, one of the most popular being sameID.net.

I wanted to see whether the person or organisation behind вштабе.рф was running any other sites from the same Analytics account. Viewing thewebsite’s source code gave me the all-important Google Analytics ID number. When I performed a broader search on it, the results were surprising—it was linked to no less than seven other websites (archived copy).

These included whoswho.com.ua (archive), apparently aimed at collating compromising information on Ukrainian officials, whilst purporting to be a Ukrainian project; Zanogo.com (archive), another repository of memes, many anti-Western; and yapatriot.ru (archive), which appears to be an attempt to discredit Russian opposition figures. Another of the websites using the same Analytics account was syriainform.com (archive), a site seemingly promoting an anti-US and pro-Assad slant on events in Syria.

Most striking of all was the presence of Material Evidence—a website for the touring photo exhibition that has featured in several media investigations into its alleged pro-Kremlin connections. In 2014, Gawker reported on the New York show, commenting on its large, well-funded advertising campaign. They noted that its website was registered in St. Petersburg, which is confirmed by historic WHOIS records.

Down the Rabbit Hole

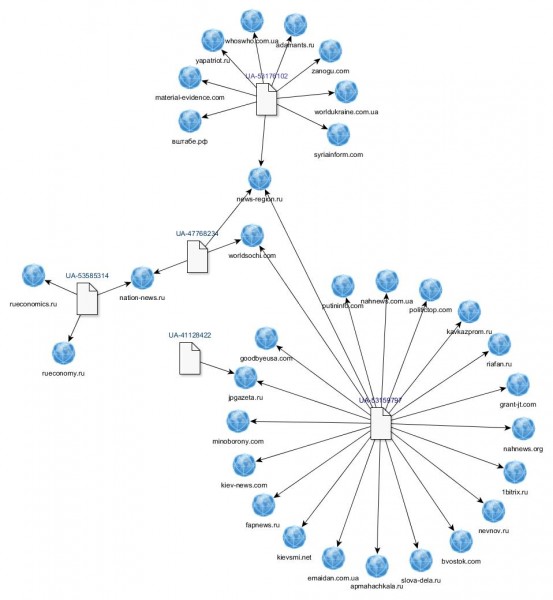

Whilst investigating the network of sites tied to account UA-53176102, I discovered that one, news-region.ru, had also been linked to a second Analytics account: UA-53159797 (archive).

This number, in turn, was associated with a further cluster of nineteen pro-Kremlin websites. Subsequent examinations of these webpages revealed three more Analytics accounts, with additional sites connected to them. Below is a network diagram of the relationships I have established to date.

At the time of writing, the Analytics codes remain unchanged and visible on most of these sites. My findings can easily be verified by viewing their source code, either in the browser or by saving the page and viewing it in a text editor.

Besides Google Analytics, the websites had some other common traits: shared use of Yandex Metrika, Yandex Verification, and a Nginx server—all Russian-made tools—characterized the sites in the network.

It became clear that I was most likely looking at a large, well-organised online information campaign. But whilst the Google Analytics code demonstrated shared involvement in and management of the websites, it couldn’t tell me who was behind them.

A Personal Connection?

Spurred on by curiosity, I did a little more digging through publicly available information. Domain registration records in several places [1 2 3] revealed a second common factor: the e-mail address [email protected]. [Archive: 1 2 3 4]. I found it to be associated not only with the majority of sites I had already identified, but also with a new group of websites, apparently still under construction. Their titles suggested themes similar to the existing network: either overt pro-Russian polemic, or more subtle disinformation under the guise of legitimate Ukrainian journalism. They included antiliberalism.com, dnepropetrovsknews.com and maidanreload.com.

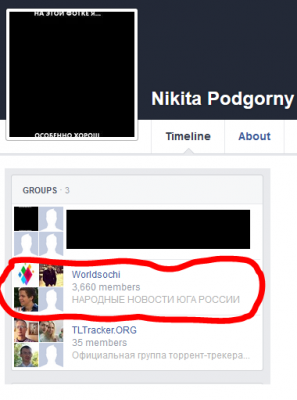

It took less than a minute of searching to link the e-mail address to a real identity. A group on Russian social networking site VKontakte [archive] lists it as belonging to one Nikita Podgorny.

Podgorny’s public Facebook profile shows he is a member of a group called Worldsochi—the exact same name as one of thewebsites linked by the two Google Analytics codes I examined.

Podgorny has a Pinterest account with only one pin [archive]—an infographic of Russia’s space accomplishments taken from a site called infosurfing.ru. Whilst infosurfing.ru doesn’t have an embedded Google Analytics code, it shares some similarities in image construction with several sites in the pro-Kremlin network.

The online FotoForensics tool shows that images from infosurfing.ru [1 2 3], putininfo.com [1 2] and вштабе.рф [1 2] contain metadata sourced from the exact same version of software: Adobe XMP Core: 5.5-c014 79.151481, 2013/03/13-12:09:15. By itself this is not a unique identifier, but it might be suggestive of a connection, especially in the context of additional information about Podgorny’s online persona.

Most notably, Podgorny is listed in the leaked employee list of St. Petersburg’s Internet Research Agency, the pro-Kremlin troll farm featured in numerous news reports and investigations, including RuNet Echo’s own reports.

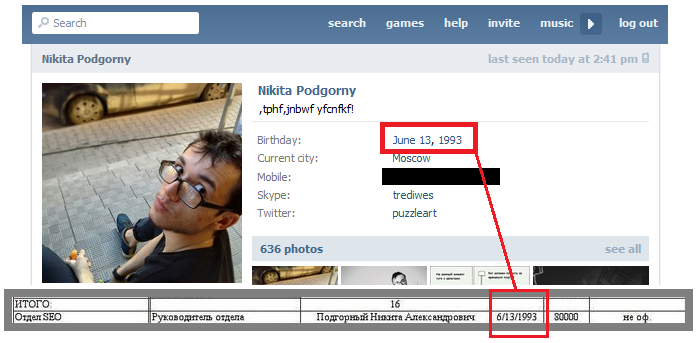

Podgorny’s date of birth, given on his public VK profile, is an exact match for that shown in the leaked document.

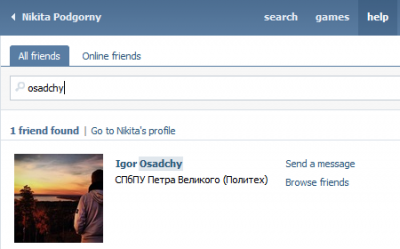

Podgorny is also VK friends with Igor Osadchy, who is named as a fellow employee in the same list. Osadchy has denied working for the Internet Reseach Agency, calling the leaks an “unsuccessful provocation.”

When contacted by Global Voices, Podgorny neither confirmed nor denied involvement in the websites, and would not comment further.

In the next post on the pro-Kremlin website network, we will look in more detail at the content, the aims, and the ideology behind the websites.

RuNet Echo author Aric Toler contributed translation and interpretation for this post.

By Lawrence Alexander, Global Voices