Beyond the Age of Post-Truth?

Thus far, in our series we have presented five titans of thought in relation to disinformation. Now we will turn to one who also became a cultural superstar of sorts: Friedrich Nietzsche. For some, this tragic prophet of the age of post-truth is a liberator from all dogmatism; for others, a dangerous opener of the gates of nihilism. We will argue that his “perspectivism” might be less lethal for the survival of truth than some think.

Nietzsche – the Birth of the Tragedy

For Nietzsche, philosophy cannot be separated from the philosopher. Nietzsche’s own life was tough and sad yet carries some tragic glory. He was born in 1844 in Röcken, Germany, as the son of a pastor. As the son of a child prodigy, his family expected he would become one as well. His father died when he was five and the young Friedrich was sent to an extremely strict school. After becoming the youngest professor of classical philology in Basel ever, he wrote The Birth of Tragedy. The book proposes that healthy cultures should find a middle between Apollonian (logical, harmonious) and Dionysian (chaotic, ecstatic) forces. In a time that was deeply Apollonian, it was not well received. Much later, it became influential in psychiatry (Jung), philosophy (Foucault), and art (Rothko). After that setback, however, Nietzsche gradually withdrew from academia; from to 1879 to 1889, he lived without fixed address, wandering in the Alps and Italy. As most of the time he was plagued by severe health problems, he wrote a streak of books in the short periods he felt well.

Death and Disinformation leading to Brown Reception

In 1889, at just 44, Nietzsche collapsed in Turin, after which he completely lost his mental faculties. The remaining ten years of his life – he died in 1900 – he lived in the care of his mother and of his sister Elisabeth while his work gradually attracted more attention, something Nietzsche himself was not aware of.

A photograph of Nietzsche with his mother after his collapse. Source: Wikimedia

A large part of Nietzsche’s dark reputation dates to that period, when Elisabeth worked hard to popularise her brother’s work amongst circles of the emerging extreme right, which, conveniently, also lifted her social standing. In a move of disinformation avant la lettre, she even forged nearly 30 letters and rewrote many passages of his books. For example, a concept that was distorted in the wrong hands was that of Übermensch. For Nietzsche, this term refers to a possible future, signalling that man as he currently exists is just a phase in an evolutionary process, moving from bacteria to Bach towards an unknown future. Thinking you already know the outcome of that process, thinking even that your race is the outcome, contradicts Nietzsche completely. Among philosophers, he was rehabilitated from the 1950’s onwards and in 2019 a new biography established that Nietzsche’s political thinking was, if anything, more European than nationalist, that he deeply regretted the violence of the German-Franco war, that he had several Jewish friends, and that he was among the very few professors at Basel University voting in favour of admitting women. Yet as the hijacking of his ideas can never be undone, and the hijackers consequently led the world into an unparalleled catastrophe, the shadow remains.

The Impossibility of Nietzscheanism

It is hard to give a brief overview of Nietzsche’s thought; Nietzsche never created a coherent “philosophy”, a system of thinking. He called himself the “philosopher of maybe”. Instead, an important element is the recognition of the chaotic and dynamic nature of reality. One has to affirm chaos, according to Nietzsche: “One has to be chaos to give birth to dancing stars”.

One could say that Nietzsche, in order to create more chaos, put gunpowder into the canon of philosophy, including the thinkers we covered earlier in our series.

Nietzsche called Plato a sophist himself. Moreover, Plato’s objective ideas behind the phenomena we perceive are life-denying, as they only reflect the psychological weakness of not being able to accept truth. Projecting this inability on religion, he called Christianity “Plato for the masses”.

Although Nietzsche appreciated Aristotle more than Plato, he would still dismiss Aristotle’s teleological ideas (everything has its fixed function) as fairy tales.

The empirical tradition of Hume and Mill in Nietzsche’s eyes is philosophically naïve: “This is not a philosophical race – these Englishmen”.

Nietzsche is tough on Kant as well. In rash terms, he called him intellectually cowardly, as he tried to save the idea of human autonomy from empirical science.

At the same time, his writing is so rich in different perspectives, Nietzsche cannot be reduced to one position or his apparent dismay of other philosophers. There is always another side.

Although Nietzsche attacks Kant harshly, one could also say Nietzsche did not sweep away his thinking, but continued it, radicalised it even. How does this work? As we wrote before, Kant explained that we can never have direct access to the things themselves (Ding an sich), but only through a medium (our consciousness). Take this example: if you look up from your screen, you see the ceiling (if you are indoors). However, this is actually fictional, a story made inside your brain. Instead, something else happened: the retina behind your eyes catches reflections of light bouncing off some object. Your brain creates the meaning of this process into a static image: the ceiling. It needs the concept of “ceiling” to be able to do this.

While Kant thought there was a certain rationality in the use of these concepts, Nietzsche, inspired by Arthur Schopenhauer, came up with a different interpretation. Very crudely, both Nietzsche and Schopenhauer would say that everything in the light-ceiling-retina-consciousness example behaves as it does because it desires to will. Nietzsche famously says in The Genealogy of Morals that man would rather will nothing than not will at all. Nietzsche departs from Schopenhauer, however, when he argues that will is directed and constantly striving, while Schopenhauer contended the will had no sense of purpose.

Reinventing the Sacred in Post-Religious Times

Based on his ideas on chaos and will, Nietzsche criticised modern culture. In the Gay Science, he presents a parable that illustrates how far he is ahead of his own time. The story is about a marketplace where a madman shows up with a lantern. He shouts that he is looking for God. The people in the market are amused and mock him: “Why! is he lost? said one. Has he strayed away like a child? said another. Or does he keep himself hidden? Is he afraid of us? Has he taken a sea-voyage? Has he emigrated?… The insane man jumped into their midst and transfixed them with his glances. ‘Where is God gone?’ he called out. ‘I mean to tell you! We have killed him,—you and I!’”

This tale tells us two things. First, God is dead, meaning we now live in the age of scepticism, of intellectual chaos. However, this is not something which is applauded by Nietzsche. Because secondly, he wants to show that the people do not understand the implications of what has happened. Modern humans have only replaced the image of God with something else (the market, the dignity of man, progress) but the way of thinking, the grammar of God, remains in place. According to Nietzsche, we have given ourselves freedom, but we lack the mental power to use it. He wants to create space for a modern sacred attitude in duality with modern scepticism.

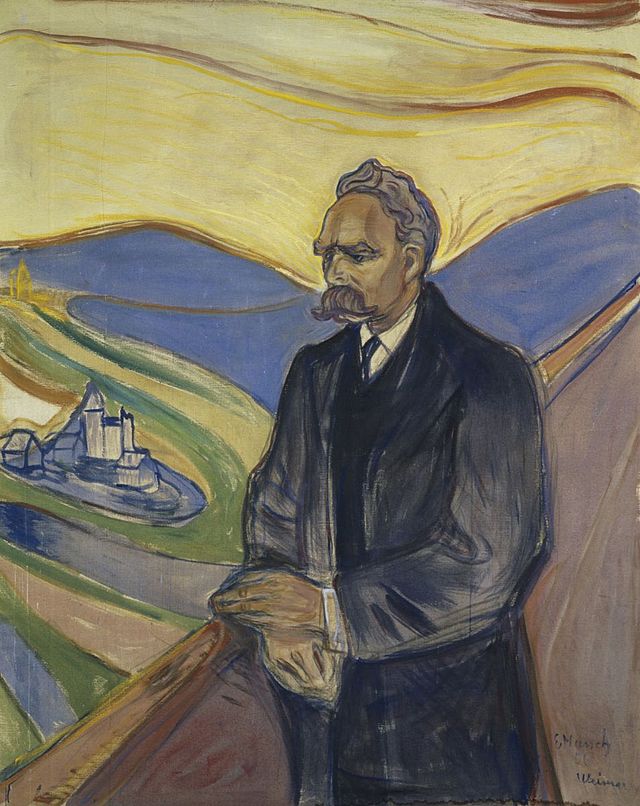

“Portrait of Friedrich Nietzsche” by Edvard Munch. Source: Wikimedia

Beyond Post-Truths…are Truths!

To Nietzsche everything part of reality is chaos, or struggle. This means that everyone making claims about the truth should realise he does never offer the truth, only an interpretation of it. Contrary to how some have interpreted this, this does not mean that Nietzsche does not care for truth. He cares so much about it he warns about scientific hubris claiming to have the Truth.

According to Nietzsche, this does not have to lead to a state of mind in which everything is futile or morally acceptable. His work suggests it is possible and necessary to overcome nihilism by establishing an attitude of strong scepticism. This refers to a truth practice based on perspectivism: not aiming to find static truths about reality, but becoming a truthful person.

Fake News and Disinformation

Because truthfulness is important for Nietzsche, he would despise spreaders of disinformation. One who spreads disinformation implicitly acknowledges he is weak. Nietzsche also warns that one cannot separate a claim on the truth from the person making that claim. This does not mean we have to give in to total relativism. It does not mean that all reasons are equally valuable and thus no one really is. Nietzsche is ruthlessly logical in his thinking. Instead, it means we have to be alert and always ask questions: who is making this claim? What are their interests? Maybe in general it is healthy for a society to be somewhat sceptical towards those that have power. Actually, this is what EUvsDisinfo is doing with state-sponsored media which we have strong reasons to believe are designed to create or stimulate tensions in our democracies and advance Kremlin interests.

However, Nietzsche might be more relaxed about misinformation or “fake news”. Of course, there is a lot of wrong information, or claims that appear to be wrong or prove to be wrong in hindsight. This is inevitable given the chaotic nature of the world (plus all the noise machines at our disposal). The fact that people are upset about it perhaps also betrays unreasonable expectations about truth and the public debate. It seems to deny the reality that the truth can be messy. Disinformation, on the other hand, often takes advantage of that messiness and the disappointment about it. This does not imply we should not take seriously the danger of spreading misinformation. Yet, we should realise the phenomenon itself is an inherent part of reality.

Anything Goes? Probably Not

So if we are experiencing Nietzsche’s prediction of a post-truth age, how worried should we be? According to him, it does not need to be as gloomy or hollow as one would imagine. If Nietzsche was right in claiming that our positions are just perspectives on truth, this does not mean that we have to live within the boundaries of those perspectives. Alexis Papazoglou, who wrote about Nietzsche and post-truth, argues that if we increase our awareness of different views, it becomes more likely that we are able to reach something close to “objectivity”. Psychologically, this might be easier if we drop the notion of objectivity, which always seduces people to think one is right and the other is wrong. In his book On the Genealogy of Morality, Nietzsche writes:

The more eyes, different eyes, we know how to bring to bear on one and the same matter, that much more complete will our “concept” of this matter, our “objectivity” be.

In these times, which are both connected and more alone, sincerely listening to people with different views – integrate, like Nietzsche, as many views as possible – seems vitally important.