By Michael Rühle, for CEPA

Russia’s assault on Ukraine in the spring of 2014 has led to the biggest adaptation of NATO’s collective defense for a generation.

By deploying several multinational battlegroups in NATO’s easternmost Allies, by enhancing its presence in the Black Sea, increasing readiness, adopting an ambitious exercise schedule, and increasing defense spending, NATO demonstrated that the collective defense pledge enshrined in Article 5 of its Treaty remains tangible and real.

However, to make NATO truly future-proof, it must continue to broaden its approach to security. NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg’s call for greater resilience as the first line of defense – a major element of his NATO 2030 initiative to make the Alliance more united politically, more capable militarily, and more connected globally – points to the challenges NATO must meet: in today’s strategic environment, adversaries use more than tanks and troops. Cyberattacks are hitting nations below the threshold of a kinetic attack, social-media campaigns create alternative realities that seek to destabilize political communities without soldiers crossing borders, and the “hybrid” combination of military and non-military instruments creates ambiguities that make NATO’s situational awareness and speedy decision-making more difficult.

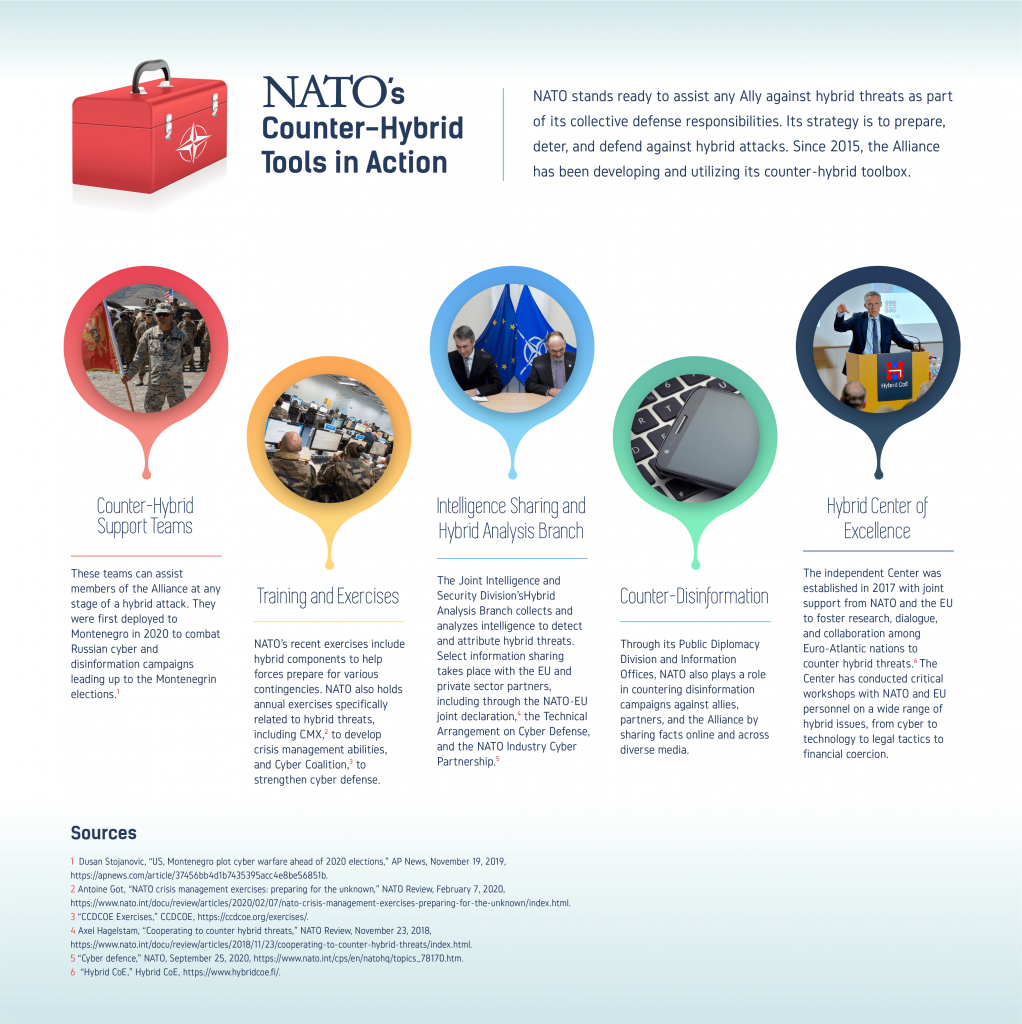

To cope with these kinds of threats, NATO is consistently broadening and refining its counter-hybrid toolbox. For example, Allies have stepped up intelligence-sharing, including the quality and quantity of analyses on hybrid challenges. Moreover, by introducing hybrid elements into NATO’s exercise scenarios, political and military decision-makers are confronted with the challenges of coping with attacks that involve kinetic and non-kinetic approaches, and take place in an ambiguous information environment. NATO’s public diplomacy efforts, in turn, have become more refined in detecting and responding to disinformation campaigns, quickly rebutting false information and setting the record straight, and conducting information campaigns that increase the understanding of NATO among its own populations.

Allies have also started to develop comprehensive and preventive response options, with the view of integrating military and non-military tools to counter hybrid activities. In the area of emerging and disruptive technologies, NATO is looking at how potential aggressors could use such technologies in hybrid campaigns. Cooperation with the European Union (EU) continues to deepen. NATO and the EU developed so-called “playbooks” and “operational protocols” to help align their responses to hybrid threats. Mutual briefings on the hybrid landscape, as well as on the specific threat picture, have led to a closer relationship between the organizations. NATO and the EU also work closely with the Helsinki-based European Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats, participating in conferences and exercises.

Another key element in NATO’s toolbox is the counter-hybrid support team concept. Such teams consist primarily of civilian experts who could be sent at an Ally’s request in a crisis, but given its expertise in counter-intelligence or the protection of critical infrastructure, it can also advise on setting up national defense structures better geared towards meeting hybrid threats. In November 2019, the first counter-hybrid support team deployed to Montenegro, then a new NATO Ally seeking to mitigate vulnerabilities.

Resilience is another important element of NATO’s approach to tackling hybrid threats. Since most hybrid attacks are aimed at individual nations, NATO must help ensure that each member country is resilient enough to perform, for example, when the Alliance is preparing to send military reinforcements during a crisis. While the strengthening of resilience is a national responsibility, NATO has produced guidelines that can serve as benchmarks for national self-assessments in areas such as energy or communications. These requirements are regularly updated in the face of new developments, such as the introduction of 5G communications technology.

Allies have also started to systematically analyze China, a country that presents both challenges and opportunities. Regarding hybrid activities, Allies have started to examine their own vulnerabilities to Chinese action, including political and economic influence. Finally, Allies are also trying out new meeting formats. For example, in May 2019, the first ever informal meeting of the North Atlantic Council with national security advisers and other senior officials took place, focusing on need for a whole-of-government approach to meet hybrid challenges.

NATO’s adaptation to a new hybrid conflict landscape has been remarkably swift. Many challenges still remain. However, as Secretary General Stoltenberg put it, we have to be prepared for the unforeseen and thus need a strategy to deal with uncertainty. Broadening NATO’s counter-hybrid toolbox is a vital part of such a strategy.

By Michael Rühle, for CEPA

Michael Ruhle is Head, Hybrid Challenges and Energy Security Section, Emerging Security Challenges Division, NATO. The views expressed are the author’s own.

Europe’s Edge is an online journal covering crucial topics in the transatlantic policy debate. All opinions are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the position or views of the institutions they represent or the Center for European Policy Analysis.

Photo: NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg. November 25, 2020. Credit: NATO