A short guide to communicating with someone who believes in anti-vaccine conspiracy theories.

“Vaccines are very important and not scary at all. Done in a flash!” a marabou bird reassures a vaccine-hesitant (and terrified!) hippo in a 1966 Soviet cartoon. More than 50 years later, amid the global COVID-19 pandemic, vaccines are as important as ever, but the messages carried by pro-Kremlin media are less reassuring.

Throughout the pandemic, unfounded claims about vaccines originating from the darkest corners of the Internet, such as “Bill Gates will use vaccines to microchip humanity”, have found new momentum in pro-Kremlin disinformation outlets. All sorts of misleading health information continues to make the rounds on social media, causing confusion and further aggravating the health crisis.

Many would find claims about Microsoft “microchips” in vaccines simply absurd. But what about those who don’t? How do you actually talk to someone who embraces vaccine-related conspiracy theories they encounter online?

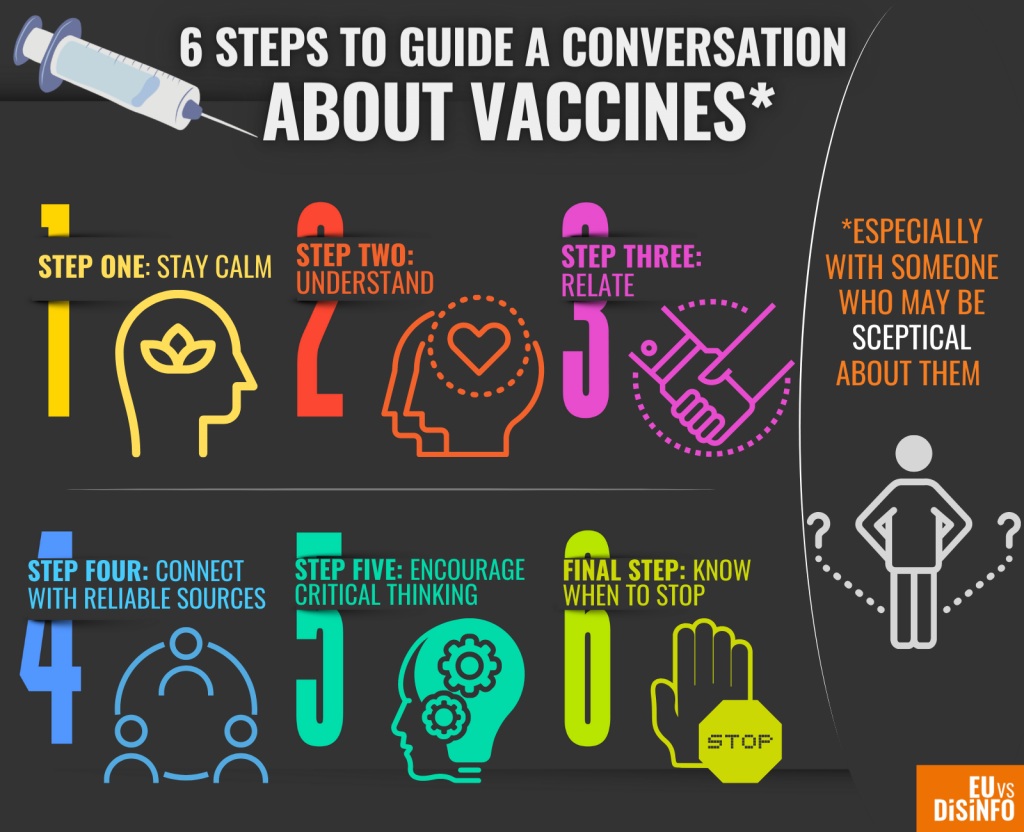

Here are a few tips that may be helpful:

If you come across disinformation or conspiracy theories about vaccines on social media, a good rule of thumb is to report such posts to the platforms, as they are likely to go against their policies. Engaging with such content (even by leaving a negative comment) may only help it spread further.

What if this person who believes in and shares misleading claims and outright conspiracy theories about vaccines is someone close to you – a friend, a loved-one, a neighbour? Assertions that the Pope demands his followers to get vaccinated as a service to global pharmaceutical companies might seem ridiculous, but mocking, shaming or getting angry at someone who is actually concerned about it can be counter-productive.

Regardless of educational background, people can have hesitations and fears which may stem from valid concerns about vaccine safety and efficiency. Approaching others with respect and willingness to listen is key to having a meaningful and impactful conversation.

It is well documented by academic research that we tend to make up our minds about vaccines based not only on scientific facts or medical arguments but also on social, cultural, economic and political factors, on personal experiences and on moral convictions. In short, the reasons for believing unfounded claims about vaccines go far beyond a simple lack of knowledge.

A 2017 study in Nature Human Behaviour found statistically significant relations between vaccine hesitancy and moral values in two large groups of American parents. People who were highly vaccine-hesitant were influenced by beliefs that vaccines would pollute the “pure” bodies of their children. They also believed that governments should not “control” individual behaviour.

Disinformation actors understand quite well how to abuse and exploit such beliefs. Unfounded claims on social media alleging that vaccines can modify human DNA or that they are tainted with HIV, malaria or “5G particles” appeal to emotions rather than facts. Such claims tap into deeply held beliefs about the need to protect our bodies (and those of our children) from anything that is “unnatural”, “dirty” or “dangerous”, portraying vaccines exactly as such.

In a similar manner, claims that COVID-19 vaccines will be used as a pretext to “microchip” and control humanity aim to exploit our feelings about liberty and individual autonomy (after all, vaccination policies evoke elements of collectivism).

Realising that one’s moral beliefs might be manipulated is a difficult and unpleasant process. Try to encourage critical self-reflection by asking questions about anxieties and fears related to vaccines. And be prepared to listen without judgement.

People who hesitate about vaccines probably do not want to intentionally harm themselves or their loved ones. As one parent put it succinctly during her TED talk, when it comes to vaccines most parents are “utterly terrified of doing the wrong thing”.

In a sense, vaccines are a victim of their success. We read about diseases such as smallpox in history books rather than on news websites, precisely because vaccines helped eradicate them. But that also makes the risk (however small) of potential vaccine side-effects more “real” than the threat of a disease itself.

Could that be a case with your loved one/friend/neighbour? Are they afraid of a vaccine more than of a disease just because the latter seems like a more distant threat? Keep in mind that some disinformation actors, including pro-Kremlin media and their proxies, have spread claims that fuel exactly these sentiments, for example by alleging that the coronavirus crisis was manufactured by the media or by “Big Pharma” to pursue business interests.

Establishing some common ground over the (hopefully) shared need to make the best decision regarding one’s health opens an opportunity for dialogue. Avoid having a “series of rebuttals” which can lead to antagonism and anger. Try to relate on an emotional and personal level. Why is it important to you that they do “the right thing” when it comes to vaccines? Admitting that you are worried about their well-being could be a powerful stimulus for them to reconsider their views. Personal stories telling why you are confident about vaccines (and you can read more about safeguards on vaccine safety) can often be more convincing than abstract reasoning. It is important to do so as the mere exposure to a conspiracy theory may have adverse consequences, even among people who don’t subscribe to the conspiracy theory.

Recently, the Atlantic Council highlighted research which found that anti-vaccination clusters online employ more diverse narratives than pro-vaccination clusters. To put it simply: anti-vaccination claims are rarely just about vaccines. They engage in broader topics related to (alternative) health and general well-being. As such, they cast a wider net than traditional vaccine-advocacy stories centred on scientific data and communication from health agencies.

For example, a Facebook page devoted to “alternative” medicine and targeting Ukrainians makes a series of claims linking coronavirus vaccines with “dangerous” nanoparticles and 5G technologies. The same page also advocates the wonders of Ayurveda medicine and the benefits of coffee for cancer patients.

This is not to say that coffee and Ayurveda are necessarily harmful, but people following such topics on social media may unwittingly be exposing themselves to misleading and harmful information about vaccines. Furthermore, if more people believe certain ideas to be true, we are also more likely to accept them as such. That is why your presence in conspiracy theory and disinformation bubbles helps those views become entrenched in our own thinking.

If your loved one or friend is in a similar “alternative” bubble, encourage them to follow pages and people sharing interesting and reliable, fact-based content. Connecting with scientists, academics, independent media, fact-checkers and similar communities is a good way to build immunity to disinformation online, including about vaccines.

People who embrace conspiracy theories often consider themselves critical thinkers. It is no coincidence that the flagship pro-Kremlin disinformation outlet, RT, calls on its audiences to “question more”.

But as this helpful article on BBC points out, the spirit of doubt is actually a key opening for rational thought. The aim is not to make the other person less curious or sceptical but to change what they are curious or sceptical about. And start asking questions.

Conspiracy theories tend to portray complex realities in broad and sweeping strokes, explaining “everything” and providing answers to all possible questions at once. As sociologist John Gagnon has argued, “the difference between a scientific theory and a conspiracy theory is that a scientific theory has holes in it”. At the times of the global pandemic, the “know-it-all” certainty offered by conspiracy theories can become a source of relief from everyday anxieties. Consider whether the other person might be turning to dubious sources to satisfy their need to know.

Besides, disinformation is used not only for political but also for commercial purposes. According to the Global Disinformation Index, a quarter billion dollars is paid annually to thousands of disinformation sites by ad tech companies placing adverts for many well-known brands. Websites advocating “alternative” health remedies instead of vaccines frequently carry ads for dubious food supplements, trying to get direct financial gain from their visitors. Followers of social media can also be “monetised” by disinformation actors, or used for reputational gains.

Try asking the other person whose voices on health and vaccines he or she chooses to trust and why. Encourage them to reflect on how they seek and assess information, including thinking about the motives of those who share anti-vaccination messages.

If you follow these steps, you may able to have a constructive conversation and eventually lead your friend or a loved-one out of a conspiracy rabbit-hole. But do not expect quick results.

Our views and feelings about health and well-being are deeply personal and complex, and unlikely to change overnight. Besides, as Mark Lorch, a professor of Communication and Chemistry at the University of Hull, points out, new evidence creates inconsistencies in our views, which can cause emotional discomfort. So if you press too much, there is a risk that the other person will come up with justifications and actually strengthen his or her views, despite the evidence against it.

By showing compassion to the other person, even if you stand firmly against conspiracy theories, you can already make a difference in the complicated and anxious atmosphere fostered by the global pandemic.

And if you succeed, you can always show your friend, loved-one or neighbour the cartoon hippo. Remember, vaccines are very important and not scary at all!