Moldova’s gas pipes were losing pressure while Russian political pressure, in the form of threats to cut off gas deliveries, was rising on the recently elected, pro-reform Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS) government. The PAS came to power in July promising an EU-oriented Moldova.

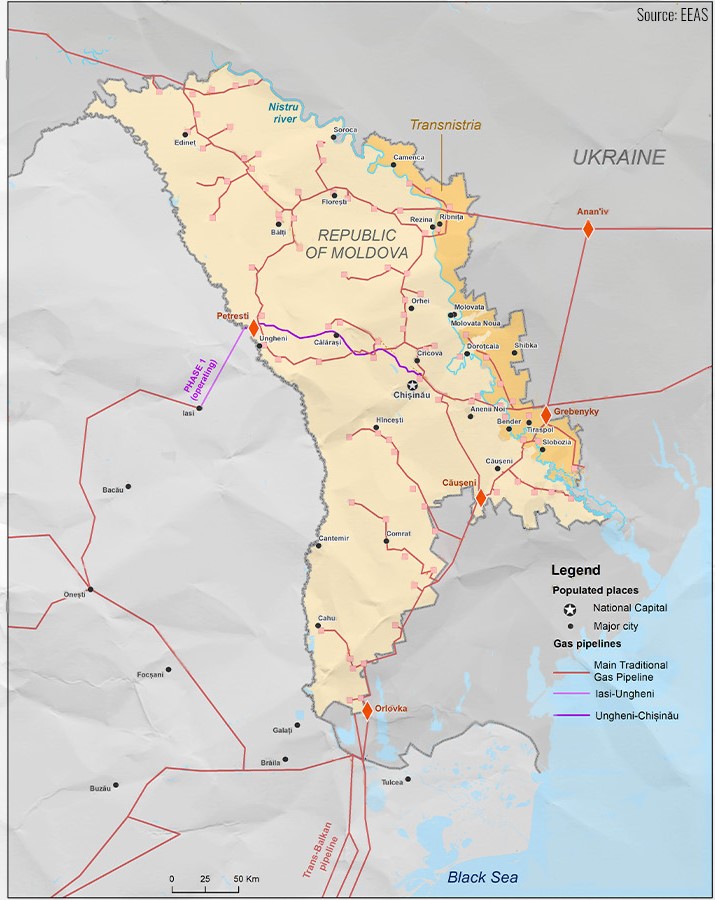

Last month, a gas price crisis was engineered in what seems timed to the approaching winter season, using gas as a geopolitical weapon. The Russian state gas company Gazprom increased prices for gas deliveries to the joint Russian-Moldovan gas company Moldovagaz from $ 550 to $ 790 per thousand cubic metres and reduced the amount of gas by about one third. Moldova declared a state of emergency and began importing gas from other countries, with EU assistance, after the contract with Gazprom expired at the end of September.

Tell me the price

How much should Moldova be charged in a new gas contract? According to President Putin’s spokesman Dmitry Peskov and pro-Kremlin outlets following his lead: Gazprom offered a fair price based on a commercial decision.

The claims, accusations, and disinformation

Besides Peskov’s first narrative of ‘just business’, we can identify other main narratives circulated by the pro-Kremlin media ecosystem that seek to explain why the gas crisis developed, who was to blame for it, and what was necessary to resolve it.

‘Contracts expire, now the Russophobe Sandu must pay’

The context is that the Kremlin lost its loyal ally in the Moldovan government, former President Igor Dodon, in 2020. Now the reform-oriented policy of current President Maia Sandu and her government must come with a price, in the Kremlin’s view. Some narratives pushed by Russian state media outlets are built around the idea that the West is encircling Russia and hatching a conspiracy against it. Examples include these quotes from Russian state TV’s Rossiya 1: ‘Russophobe Moldova is a pawn in Washington and Brussels’ chess game’ and ‘Sandu plays along with also-Russophobe Kyiv when joining the Crimea Platform. Sandu must pay the price and be punished for this.’

Russian state-owned outlets in Moldova such as the local version of the Sputnik news agency or Komsomolskaya Pravda, the largest paper in Moldova and Russian-owned, were particularly on the offensive. Sputnik headlines included these examples: ‘You can’t spit in the face of a country from which you ask for a discount on gas supply’ and ‘By indirectly declaring war on Russia, you can’t get a good price for gas’. The story that received the most traction on Facebook came again from the Komsomolskaya Pravda, which asked whether it is okay to ‘bite the Russian bear and then demand a discount for gas’. Now, it tells the readers: ‘Decision taken: gas is two times more expensive than before’.

Keeping in the domain of psychological phobias, a sub-narrative claimed that ‘Moldova is the victim of Western Russophobes’.

‘A plot to strangle Transnistria’

Other narratives turn the logic of ‘it’s only about money’ upside down, omitting who raised gas prices and reduced volumes. The twist was found in narratives from several Russia-based media outlets, including Izvestiya, NTV, Regnum, Fondsk.ru, and others claiming that ‘Sandu wanted to strangle Transnistria/Sandu must give assurances regarding Transnistria’. (The Transnistria region has accumulated a debt of around 10 times the amount being asked by Gazprom from Moldovagaz. There is no claim from Gazprom finding way towards Transnistria.)

‘Alternative gas providers are hopeless’

In October, Moldova looked towards the EU for assistance, which was offered on 28 October with €60 million through a new budget support programme. Moldova also looked successfully to other countries for gas imports, including Ukraine and Poland. This act was dismissed or ridiculed in disinformation spread by pro-Kremlin outlets. Key Russian state TV channels set the tone: Rossiya 1’s flagship programme 60 Minut labelled Moldova turning to Ukraine for gas as ‘ridiculous, bearing in mind that Ukraine is freezing’. Vremya pokazhet of Channel 1 called Ukraine’s promise to give gas to Moldova ‘political talk, not business’, while the Russian armed forces’ TV channel Zvezda [‘Star’] called Moldova’s decision to buy gas from someone other than Gazprom ‘a bluff’.

In the pro-Kremlin ecosystem, the media outlet heavyweights are always reproduced, regurgitated or promoted by numerous smaller pro-Kremlin media players or platforms in and outside Russia. Like pathfinders, they show the way for the crowd and their party-approved lines reach target audiences around the world in key languages.

‘The Sandu government will collapse’

The idea that Sandu’s government and Moldova itself are on the verge of disintegration is a kind of umbrella narrative collecting other tropes to demonstrate the futility of selecting a government that does not follow the line from Moscow. A number of stories were developed claiming, for example, that the economy will soon collapse, a systemic crisis is in the making, wider society functions will stop, and the coming winter will be devastating.

These ‘Kremlin Classics’ have similarities to disinformation seen in relation to political changes, most prominently the Orange Revolution in Ukraine. See cases in our database here.

What role did the disinformation play? Was it successful?

First, for the Russian domestic audience, this disinformation supports the ever-present pro-Kremlin narrative that Russia is a besieged fortress. Second, criticising Ukraine and Poland has become almost a reflex for the Kremlin.

Specific to Moldova, it is fair to assume that the disinformation increased the pressure on Moldovan authorities during gas negotiations. It created uncertainty about what demands are going to come further in the talks. Another purpose appears to have been to create uncertainty and anxiety within Moldovan society, which demanded that the authorities find a hasty a solution to the gas crisis, creating additional pressure.

In a time of crisis-related rumours, conspiracy thoughts or even panic all have a fertile ground. A government must command not only the actual substance of the crisis but also devote time and attention to managing public calm and nerve. The umbrella narrative contributes to shaking political stability or even inciting panic.

Moldova’s strategic communication

The strategic communication by the government was, compared to other situations, more pro-active, providing the population with credible information, reaching out to EU and partners, and describing specific solutions to the public. According to Moldovan observers like Ion Preasca, editor-in-chief of the Mold-Street.com economic portal, there is reason to believe that this communication helped maintain calm and limited the effect of disinformation.

The disinformation narrative claiming that ‘Moldova is the puppet of EU and US’ was effectively countered by both the Moldovan leadership and the EU by stressing that decisions would first be made in Chisinau and the EU would not be pushing in a specific direction. Yes, the EU provided support, including funding, but in response to a Moldovan request. The same time, the fact that the EU provided support was used to counter disinformation related to the gas crisis.

Where did it end?

The gas crisis has, for the time being, been solved with the conclusion of a new five-year contract including a mechanism for calculating prices. Things have calmed down: gas is flowing. Transnistria is receiving gas and is producing its part of the electricity.

A period of intense public messaging and disinformation on pro-Kremlin outlets preceded this result and created uncertainty about future energy deliveries. The Moldovan government engaged public opinion and helped calm the atmosphere. Support from the EU and partners was mobilised. This time around, disinformation did not work.

See our earlier articles on the Moldova elections here and here.