By Laura Hazard Owen, for NiemanLab

Different groups of Americans perceive news very differently: It depends on your race, gender, age, education level, and political affiliation, according to a new RAND survey of 2,543 Americans ages 21 and older. The research is part of RAND’s ongoing “Truth Decay” research.

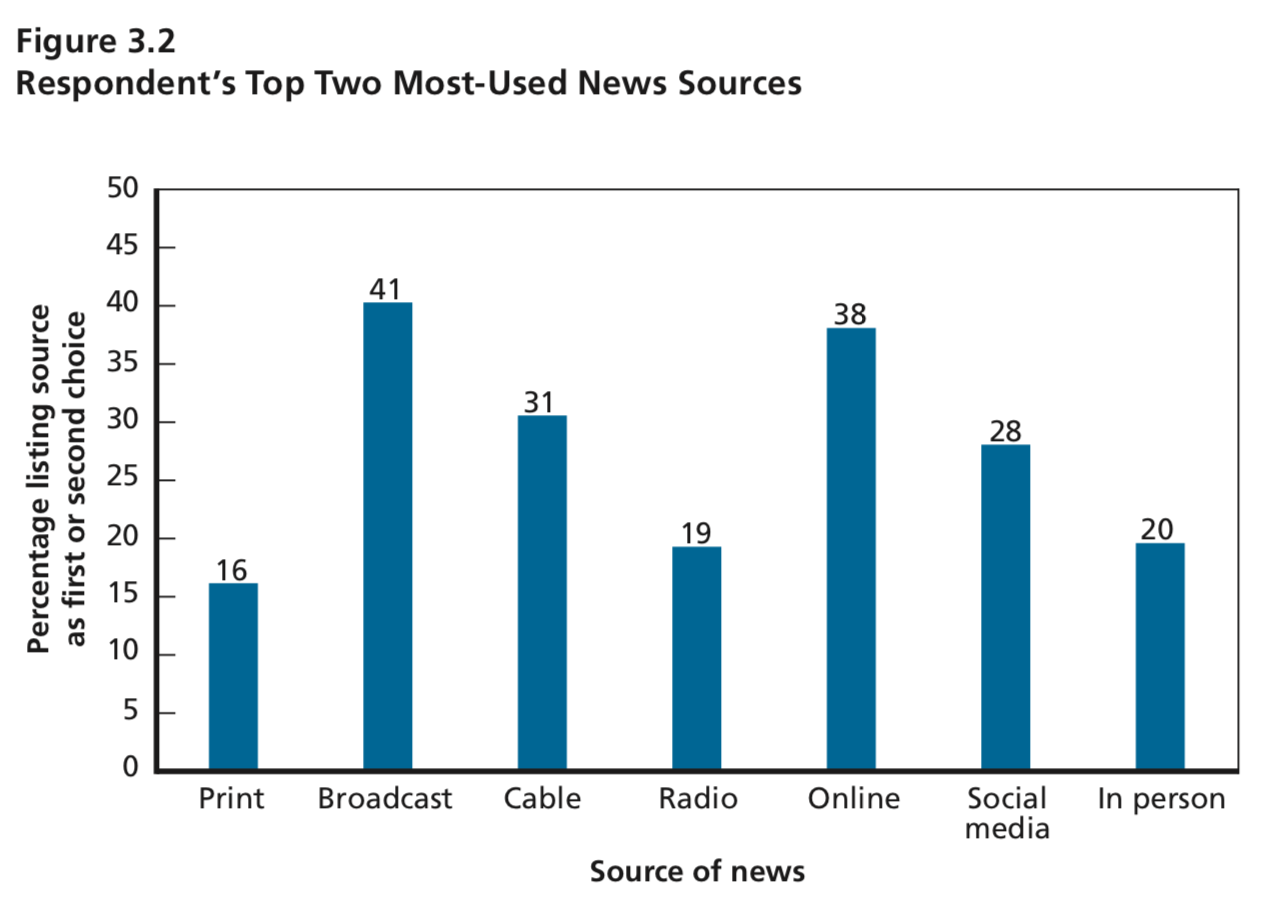

There’s plenty here that won’t be surprising to people who’ve followed research from Pew and others: People who rely primarily on print and broadcast TV for news tend to be “significantly older,” those who rely primarily on online platforms for news are younger. But RAND fleshes these categories out additional demographic characteristics.

Here are some of RAND’s findings:

— People whose primary news sources are social media and in-person contacts are generally younger and female, and they tend to have less education than a college degree and lower household incomes.

— People whose primary news sources are print publications and broadcast television tend to be significantly older, and they are less likely to be married.

— People whose primary news source is radio are significantly more likely to be male, less likely to be retired, and more likely to have a college degree.

— People whose primary news sources are online platforms are significantly younger, more likely to be male and have a college degree and higher income, and less likely to be black.

— Forty-four percent of respondents said they believe “the news is as reliable now as in the past”; 41 percent said it’s become less reliable. (And, yes, 15 percent think it’s gotten more reliable.) And this varies based on demographic:

Without attention to partisanship, respondents who were white, male, or retired or who had higher incomes or less than a college education were significantly more likely to believe the news is less reliable now (compared with as reliable as in the past). Conversely, women, racial or ethnic minorities, and those without college degrees were significantly more likely to say they believed that the news is more reliable now than in the past

Political affiliation is also a factor:

People who did not vote were less likely than others to report believing that the news is more reliable now than in the past; compared with Clinton voters, those who voted for anyone else were more than three times as likely to report a perception that the news is less reliable than in the past.

— Married people, and people who voted for someone other than Trump or Clinton, were much more likely to rate “obtaining news in person” as the most reliable method. (Married people were three times as likely to say this as nonmarried people; people who voted for someone other than Clinton or Trump were five times as likely to say this.)

— About a third of people get most of their news from platforms that they also believe are not the most reliable. “If we do not consider political characteristics, marriage is negatively associated with getting news from a reliable source,” the report’s authors note.

Social media/in-person news consumers are less likely to rely primarily on those sources that they rate as most reliable. They do not necessarily view social media or in-person sources as among the most reliable and yet still turn to these sources most often to get news. This suggests that — at least for this group of individuals (typically younger, female, white, and without a college degree) — news consumption might be driven less by perceived reliability of information and more by other factors.

We can only speculate on these factors, but literature suggests they might include interest, time, or willingness. As an example, we found that women were more likely to rely on social media and in-person channels but were not more likely to rate these channels as most reliable. One possible explanation (based on previous research on women, their daily demands, and their personal networks) is that women might find it more convenient to be informed about news through social channels (in-person, social media) that are more suited to their larger personal networks, higher levels of communication across those networks, and relative lack of leisure time compared with men.

Although this is consistent with the empirical results, it would need to be explored in more depth to directly support any conclusions.

The full report is here.

By Laura Hazard Owen, for NiemanLab