Sputnik Polska as the tip of the iceberg of a disinformation campaign.

Penetration of the information space by pro-Kremlin actors goes far beyond using state-funded media or a troll factory. As shown in the new report by Info Ops Polska, disinformation messages can be spread by multiple actors using a variety of tools – so that at the end of the day, its recipients cannot see its original source or its fake ventilation. Authors of the report take a look at one of the hot-button issues in Poland, frequently exploited by disinformation campaigns: namely, Ukrainian-Polish history and relations. It traces the road that pro-Kremlin narratives travel across cyberspace.

In the Beginning Was the Website

Poland and Ukraine share a long, rich, and sometimes painful history; the nations have a lot in common. According to different statistics, there are approximately 900 thousand to 1,2 million Ukrainian citizens living and working in Poland. The immigration started in 2014, with the deteriorating situation in eastern Ukraine due to Russia’s aggression and plentiful opportunities on offer in Poland’s economy. Given this background, the issue remains high on the political agenda of both informing and disinforming actors.

Sputnik Polska has been actively pushing disinformation narratives related to this topic. One of them touches upon social and economic issues close to the hearts of many Poles. On the one hand, it tried to push manipulative messages, blaming Ukrainians for the reduced standard of living in Poland (which, by the way, has been dynamically growing, not decreasing, in recent years). On the other hand, it tried to paint a picture of “Ukrainian slave workers” (debunked numerous times by EUvsDisinfo). This narrative’s aims were to portray Poland as a country which doesn’t treat people fairly, to exaggerate Polish-Ukrainian tensions, and to show Ukraine as a country without any prospects, forcing people to leave to become “slaves of Poland”. Adding insult to disinformation, Sputnik Polska also covered the deceptive report of the Russian Federal Supervisory Service for the Protection of Human Rights, according to which Ukrainians were allegedly bringing an epidemiological threat to Poland. This narrative spread to the mainstream media as well, and its aim was not only to portray Ukrainians in a negative light, but to question the EU visa-free travel for Ukraine.

As the Info Ops Polska report points out, Sputnik Polska has also been exploiting difficult issues in Polish-Ukrainian history, trying to evoke fear in its audience by portraying Ukraine as “possessed by fascism and by the cult of Stepan Bandera” or even responsible for a new nuclear world war.

The Pattern of Distribution

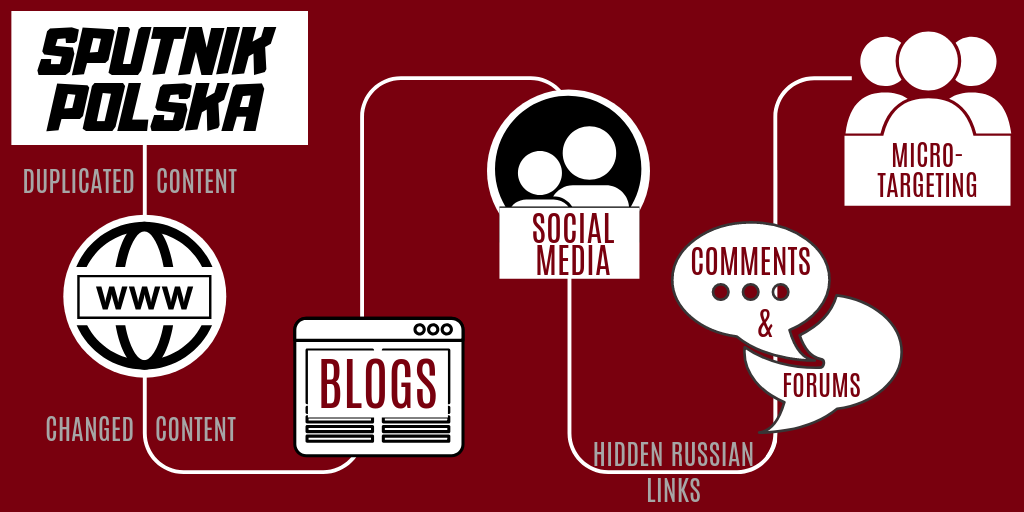

However, once a manipulative or disinforming message appears in Sputnik Polska, it marks not the end, but the beginning of an information operation. Different actors and tools are applied to spread the messages as widely as possible and target the groups and individuals who provide the biggest chance of disseminating these messages effectively.

Specifically, the content from Sputnik is duplicated (with slight changes in some cases) and disseminated through different websites, choice of which depends on the particular narrative. The next stage consists of spreading the same narratives via numerous blogs – this is the point where the content is changed, so that it reflects the familiar style of a blogger. Nevertheless, the thrust of the pro-Kremlin narratives stays the same. Next comes social media (chosen according to the message and the audience, its preferences, and vulnerabilities). Another type of interference used by pro-Kremlin actors is engaging in discussions, both on internet fora and in the comments sections of different websites. They comment and put links to either the websites (used to disseminate original Sputnik message) or blogs. They don’t usually link to the original Sputnik Polska article, because hiding the connection to official pro-Kremlin Russian sources gives the message more credibility and make it seem organic.

The final stage of the information operation is micro-targeting – where pro-Kremlin actors seek out particular small groups or even individuals in hopes of getting them to push their messages through their own channels and thus launder the origins of the messages even more effectively. The targets are identified in accordance with their preferences and vulnerabilities, which pro-Kremlin actors have recognised and analysed in depth. If the operation succeeds, a disinformation message is then spread to the mainstream – in the social and traditional media. It also paves the way for sophisticated psychological operations, and to many other gears from the Kremlin’s toolbox.

The strategy described here is another example of the Kremlin’s broader strategy of ’’information laundering’’, described already by several studies in different contexts (see examples by GMF, DFR Lab and Avaaz). The idea is to cover the tracks of original pro-Kremlin message as much as possible in order to give it more legitimacy, by creating burner accounts, using ‘’independent’’, seemingly unrelated websites, changing the content posted by social media accounts.

Apparently, laundering isn’t always about making clean.