Throughout the crisis in Ukraine, Kremlin has spent countless millions of Russian taxpayer money to impose its narrative of the crisis on the West. Unfortunately, while this task may be failing, Putin’s propaganda effort covering the war in Ukraine finds somewhat unexpected allies, like the British Stop the War coalition.

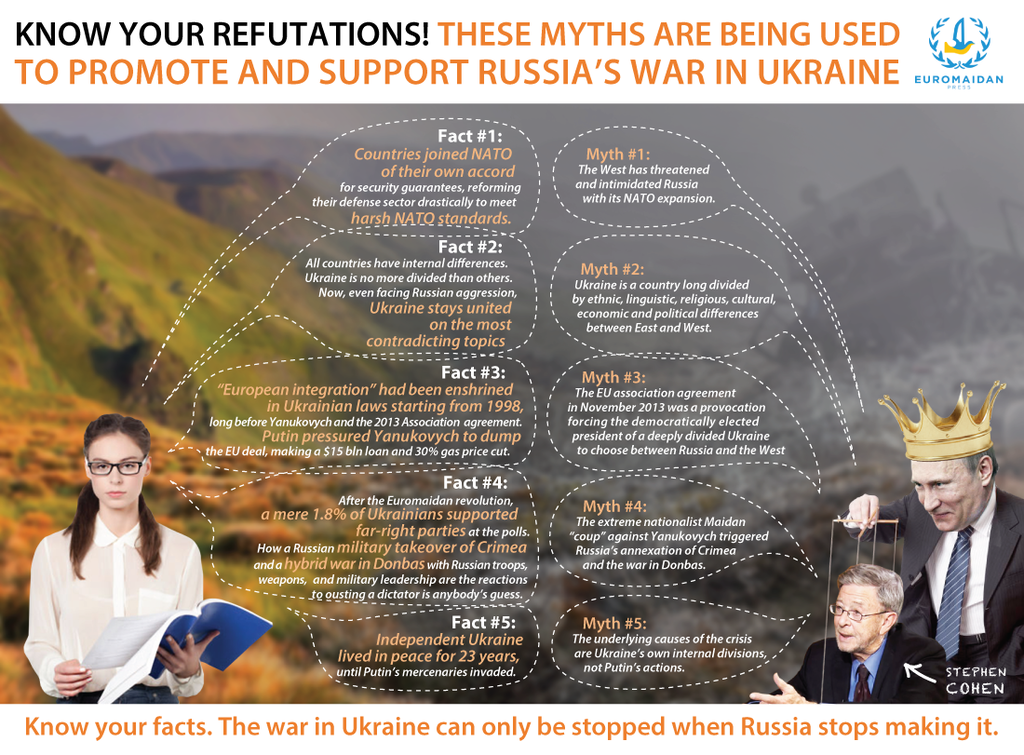

In August 2014, as regular Russian troops were pouring into war-torn Eastern Ukraine, Stephen Cohen penned an article about the “US-NATO drive to war” in Ukraine, republished by Stop the War. The article presented five purported facts and fallacies in the Western point of view on the Ukraine crisis. The resulting picture is distorted and enabling Kremlin’s war in Ukraine, to the contrary of “Stop the War’s” stated goals.

Now, as NATO has formally asked Montenegro to join the alliance on Dec,2nd , Moscow didn’t hesitate to threaten Podgorica with stopping any military cooperation if the accession becomes official. Cohen’s statements are still being used by Kremlin propaganda narrative supporters, so here are the refutations handy for the discussion with opponents.

Myth #1: The USA treated post-Soviet Russia as a defeated nation with inferior legitimate rights at home and abroad. NATO expanded into Russia’s traditional zones of national security, while in reality excluding it from Europe’s security system.

The first point, perhaps unwillingly, parrots the Soviet revanchist narrative on Russia’s post-Cold war treatment as a defeated nation. “This triumphalist, winner-take-all approach has been spearheaded by the expansion of NATO,” argues Cohen, completely oblivious to the fact that the ex-Warsaw pact nations joined NATO willingly, the older member states reluctant about the Alliance’s expansion.

The pattern seemed to repeat with Ukraine, which Cohen calls NATO’s “biggest prize”: despite Ukraine’s previous pro-democracy president Yushchenko’s will to do so, Ukraine never joined NATO during his 2005-2010 administration. Only after the Russian invasion did public opinion in Ukraine turn towards NATO, with 64% of the population willing to join the alliance in search of security guarantees.

During a recent meeting with NATO’s secretary general in Kyiv, Ukraine’s president Petro Poroshenko suggested that the reforms required for NATO membership would take as much as 6 years, and even then the Alliance issues will be decided via referendum. So far, NATO has failed to provide its “biggest prize” with lethal weapons to counter the modern Russian equipment used by the so-called “separatists”, despite numerous requests to do so.

Myth #2: Ukraine is a country long divided by ethnic, linguistic, religious, cultural, economic and political differences—particularly its western and eastern regions.

In his second point, Cohen describes Ukraine as a “country long divided by ethnic, linguistic, religious, cultural, economic and political differences ”. Perhaps Cohen would be surprised to know that even according to Soviet statistics Ukraine’s population overwhelmingly identified themselves as Ukrainians. This map from 2001, showing the percentage of Ukrainians in the country’s population, brings the point home even better. In 1991, during Ukraine’s independence referendum, a majority in every region, including Russian-occupied Crimea, Donetsk and Luhansk, voted to break free from the Soviet Union.

Ukraine’s 1991 independence referendum. “Yes” votes by regions

While some elections in the 21st century did show a divide between a pro-European West and a pro-Russian East (not unlike the electoral divides seen in many Western countries, like, for example, the US), it was Maidan that united Ukrainians in their pro-Western positions.

For example, during and after the revolution public opinion regarding joining the European Union started to noticeably shift toward pro-European direction, with the latest poll demonstrating even 57% in favor of joining the EU rather than the Custom Union (17%). As of joining NATO, Ukraine’s support for joining the alliance grew drastically in September of 2014 – exactly after Russia-backed separatists took Donbas’ Illovaysk and Debaltseve.

Meanwhile, 56,5% of Ukrainians believe that Ukraine shouldn’t concede to Russia’s aggression and has to aim on restoring control over the lost territories even if much effort is needed. Almost 70% won’t accept the idea of leaving Crimea to Russia while 65,4% are sure Ukraine shouldn’t be afraid of provoking Russia by it’s eurointegrational decisions.

“Long divided”, as put by Cohen, Ukraine miraculously manages to stay united in the face of external aggressor and show solidarity on the most contradictory topics.

Moreover, every country has its internal differences. Ukraine’s population is not more divided than, for example, the people of the US, traditionally divided between the Democrats and the Republicans, or the Poles, usually divided by liberal VS conservative preferences to the eastern and western regions.

Myth #3: The EU association agreement in November 2013 was a reckless provocation compelling the democratically elected president of a deeply divided country to choose between Russia and the West.

Cohen’s third point vehemently denies Putin’s pressure on Ukraine’s ex-president Viktor Yanukovych to dump the EU association agreement. Let’s not forget a lucrative $15 bln loan and 30% gas price cut Putin offered Yanukovych after he dumped the EU deal, to name one thing.

More than that, the “democratically elected president” Yanukovych had been consequently promoting Ukrainian integration with Europe. In summer of 2013 government even allocated funds for a pro-European promo campaign: European activists and politicians held open lectures describing the benefits of European integration.

Before that, “European integration” had been enshrined in the laws starting from 1998, long before Yanukovych.

More importantly, the description of the Ukraine crisis as a powerplay between Kremlin and Brussels is the worst example of orientalism – denying agency to the Ukrainian people, that stood up to Yanukovych regime’s turn towards the Kremlin, performing a grassroots revolution that started with a Facebook post by a Ukrainian journalist – not EU meddling.

Myth #4: Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the war in Donbas were triggered by the Maidan “coup” against Yanukovych, led by extreme nationalist forces.

Cohen’s fourth point attempts to re-tread the history of the Euromaidan movement, yet in doing so parrots Kremlin propaganda clichés of a “fascist Euromaidan” and “street radicals”.

First of all, sociology shows that any organizations, not just “nationalist forces”, played a very minor role in the protests, initially making up fewer than 10% of the protesters and later rising up to 30% of permanent Maidan camp residents, the vast majority remaining unaffiliated. While Western Ukrainians did dominate among the camp dwellers, over 45% of the non-Kyivans there came from Central, Southern or Eastern Ukraine.

The obvious radicalization of the protests was triggered by the forceful breakup of the protest in November 2013, passing laws against protests commonly known as dictatorship laws in January, and, finally, killing over a hundred of protesters by riot police and snipers.

After the Yanukovych fled the country, his own parliamentary majority turned against him in a vote of impeachment supported by the 328 of 447 MPs. 3 months later, presidential elections were held and a stable government replaced the temporary one formed by the former parliamentary opposition.

That parliament, widely believed to have been elected fraudulently in 2012 under Yanukovych, was replaced in an October 2014 election, where none of the far-right parties won seats. How, according to Cohen, Russian army invading Crimea and an Russian ex-intelligence officer entering Eastern Ukraine east from occupied Crimea with his own unit to “pull the trigger of war” are reactions to ousting a dictator, is anyone’s guess.

Myth #5: The underlying causes of the crisis are Ukraine’s own internal divisions, not Putin’s actions.

In his final point, Cohen blames the war on Ukraine’s “anti-terrorist operation” waged “mainly in Luhansk and Donetsk.” First of all, the operation never touched other regions than Luhansk and Donetsk, and secondly, it was launched days after Igor Strelkov’s unit seized police arsenals across Eastern Ukraine. During the next few months, all major successful “rebel” operations, like the battle for Debaltseve, were due to direct Russian involvement.

In August 2014, Cohen argued that “if Kyiv’s assault ends, Putin can probably compel the rebels to negotiate”. The loss of the strategic town of Debaltseve and Donetsk airport after the ceasefire was signed in September suggests that Ukraine’s anti-terrorist operation probably wasn’t the main driver of the war after all.

The alleged “long-term Ukraine’s internal divisions” didn’t manage to tear the country apart during two decades’ independency. Yet the conflict sparked as soon as Putin’s troops arrived.

“Stop the War’s” attempts to describe a Russian invasion of Ukraine as a “Russian-American conflict” and a result of Ukraine’s internal divisions at the same time does nothing to stop the war in Ukraine. On the contrary, it undermines the Western resolve which, manifested in the form of sanctions, has been one of the few things keeping Kremlin from imposing its will on the Ukrainian people. This war, which has already claimed 8000 lives and displaced over 2 million people, can only be stopped by one man: Vladimir Putin.