By Ben Dubow, Edward Lucas, Jake Morris, for CEPA

Executive Summary

- During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) spread disinformation about the efficacy of vaccines and the virus’s origins, a shift from Beijing’s previous disinformation campaigns, which had a narrower focus on China-specific issues such as Tibet, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.

- Most of Beijing’s COVID-19 narratives aimed at shaping perceptions of China’s response to the pandemic and only rarely targeted other countries specifically.

- Russia recycled previous narratives and exacerbated tensions in Western society while attempting some propaganda about Russian scientific prowess.

- The Kremlin and the CCP learned from each other. While limited evidence exists of explicit cooperation, instances of narrative overlap and circular amplification of disinformation show that China is following a Russian playbook with Chinese characteristics. Russia is simultaneously learning from the Chinese approach.

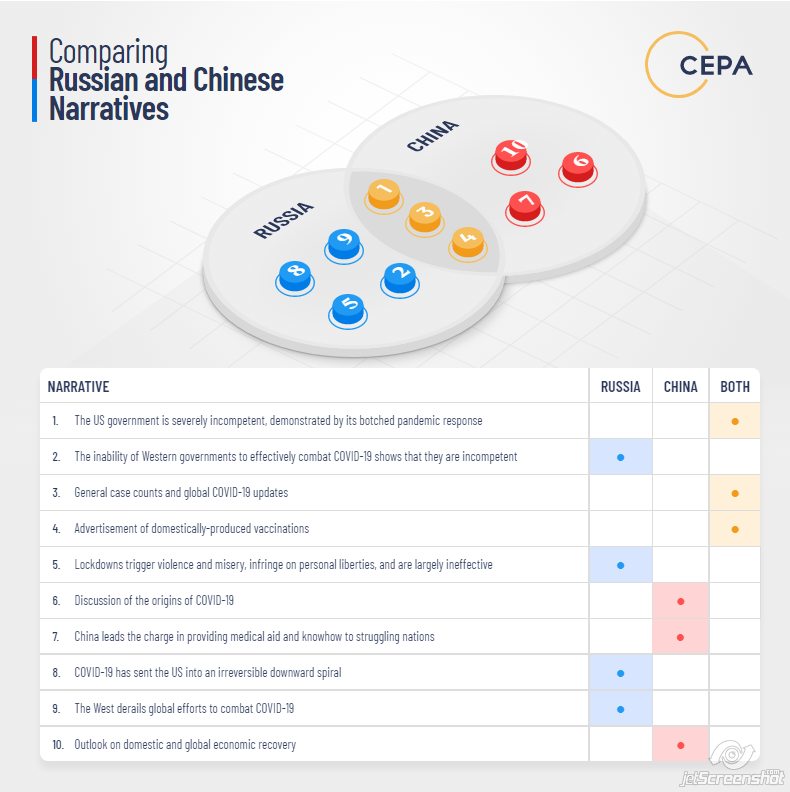

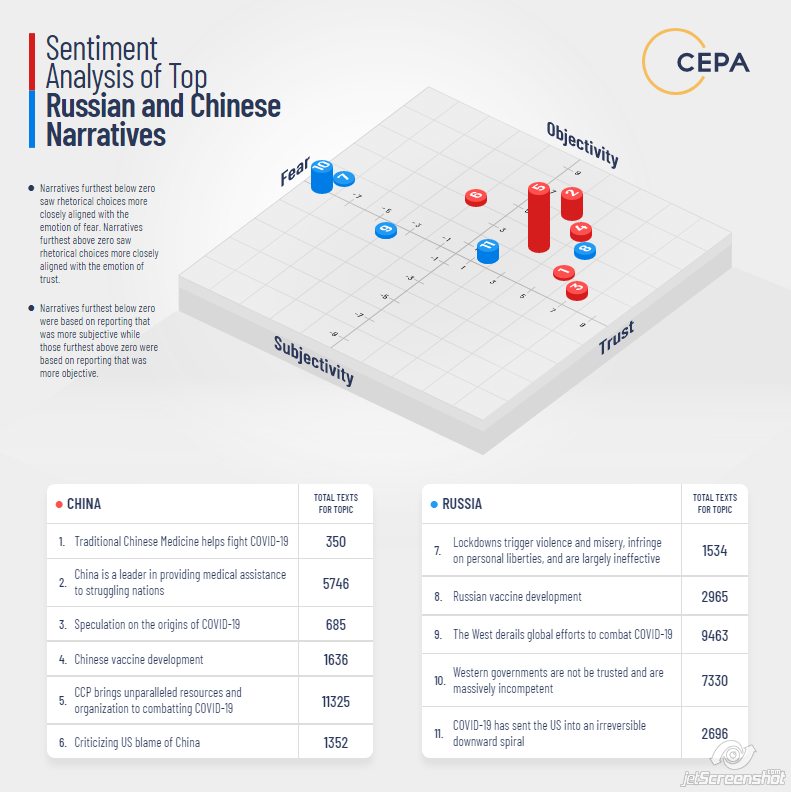

- The largest difference between China’s and Russia’s information warfare tactics remains China’s insistence on narrative consistency, compared with Russia’s firehose of falsehoods strategy.1 Even with substantially greater resources, this largely prevents Chinese narratives from swaying public opinion or polarizing societies.

- The two authoritarian countries’ information operations have evolved over the last 18 months and will continue to do so with the spread of variants, vaccines, and inquiries into the virus’s origins.

I. INTRODUCTION

The public health and economic catastrophe of the COVID-19 pandemic has also become a battle about the nature of truth itself. From the emergence of the first reports of a virus in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, opportunistic leaders in China, Russia, and elsewhere have used the virus as an excuse to further erode democracy and wage information warfare. They have inundated an already polluted information environment with disinformation and propaganda about the virus’s origins and cures, and, most recently, vaccines. Russia largely followed its preexisting playbook of using crises to inflame tensions in foreign societies. China borrowed some tools from Russia but used them for different ends, sanitizing its own record and spreading conspiracy theories on a global scale. Little evidence suggests explicit cooperation despite some instances of narrative overlap and circular amplification between the two actors. Significant differences remain in Beijing’s and Moscow’s strategies and tactics in the information environment.

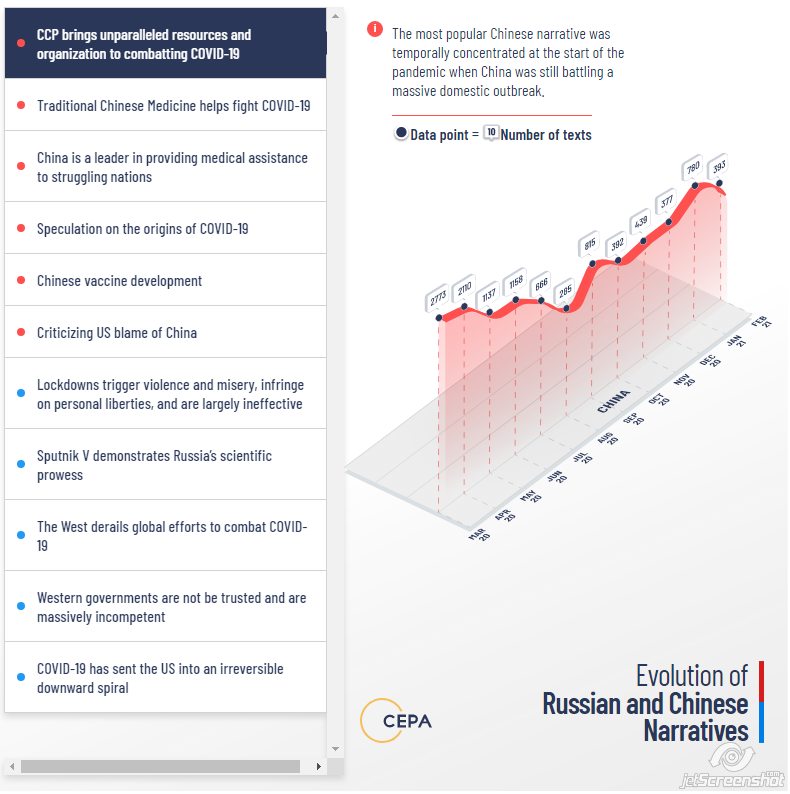

Building off of Information Bedlam,2 CEPA’s overview of academic and think tank literature written on Russian and Chinese information operations (IOs) during COVID-19, CEPA’s researchers collected and analyzed original data to complement research conducted by other think tanks and academic institutions.3 CEPA collected English-language website articles and social media messaging from Russian and Chinese government officials and state-backed media from March 2020 through March 2021. By determining rhetoric choices and the prioritization of narratives throughout the 144,000-piece database, we were able to isolate and analyze the unique tactics that Russia and China used to advance their information operations across the transatlantic space throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.

II. LESSONS LEARNED

As the world experiences vaccinations and coronavirus variants at different rates, Russian and Chinese COVID-19 information operation(IO) narratives and tactics continue to evolve. Alongside the evolution of IOs in 2021, CEPA’s data largely support the conclusions reached in Information Bedlam: The CCP deployed more destructive and conspiratorial narratives than in its previous to the information space, while Russia recycled previous narratives and didn’t substantially change its approach from previous crises. Yet the data also raise new questions and prompt a reexamination of the extent to which China is following Russia’s playbook in the information environment.

Since our last report examining the COVID-19 IO literature in March 2021, Russian and Chinese IOs have continued to evolve. Russia has innovated in spreading vaccine disinformation throughout Europe. In May 2021, social media influencers in France and Germany reported that a London-based group controlled from Moscow offered to pay them to spread disinformation about the Pfizer vaccine.4 As vaccination campaigns in the US and UK increasingly encounter problems with demand instead of supply, Russia’s misleading vaccine reporting may prove more successful.5 Vaccine disinformation will also present serious challenges in developing countries where citizens already do not trust the West and where Russia and China often have large media presences.6 Since the Biden administration asked the US intelligence community to provide a more conclusive report on the possibility that COVID-19 leaked from a Wuhan lab, the CCP has stepped up its efforts to spread conspiracies about the virus’s origins, including recirculating disinformation from early in the pandemic about Fort Detrick, a US military lab.7

In 2020, while China aggressively defended its response to COVID-19 and criticized Western efforts to combat the virus, its narratives remained mostly positive, kept China at the center of attention, and showed remarkable consistency between state-backed outlets and diplomats. Even though Zhao Lijian, the spokesperson for China’s foreign ministry, and others aggressively circulated disinformation on COVID-19’s origins and Western vaccines, the transatlantic policy and research community focused more attention on China’s destructive disinformation than the data suggest is warranted.8 This is not surprising considering the increasing bipartisan and transatlantic consensus on the need to counter Chinese influence in the information environment and, of disinformation, the shock of Chinese disinformation spreading globally for the first time during an international crisis.

While some policymakers are worried about Sino-Russian convergence in the information environment, this will be challenging because China insists on narrative consistency, while Russia opens a firehose of falsehoods.9 State-owned Russian media contradicted not only one another on COVID-19 narratives but also official Russian sources like the foreign ministry. Even though official government sources largely stayed clear of promoting disinformation on the virus’s origins, vaccines, or other COVID-19 topics, the broader pro-Kremlin information ecosystem showed no such restraint.10 The rigidity of the CCP’s control over the Chinese information environment ensures that disinformation and propaganda from state media will differ little from that spouted by government officials. Though this gives the CCP more control over its COVID-19 messaging, it also means the Chinese are much less successful than the Russians at targeting content to specific audiences, even with substantially more resources.

III. Note on Terminology

China’s COVID-19 information operations are a significant threat, but research and policy responses should be prioritized efficiently, and researchers should be clear about their definition of disinformation as opposed to broader IOs. For the purposes of this paper, CEPA defines disinformation as narratives purposefully meant to mislead and only partially based on the truth. While propaganda and other IO tools are polarizing, disruptive, and spread to support state interests, they require a different response than messages more akin to conspiracy theories than biased versions of the truth. This paper examines both disinformation and propaganda as important tools of IOs spread to support Chinese and Russian interests during the pandemic.

IV. CHINA

During the pandemic, China emerged with much more assertive IOs around COVID-19 than previous campaigns. Contrary to popular belief, China’s top messages remained relatively positive and focused on its response to the virus. This corroborates research from the German Marshall Fund that found that in 2020, half of English-language Chinese state media reporting from two popular YouTube channels was about China, while only 5% of Russian English-language state media reporting focused on Russia (also from two popular YouTube channels).11 Nonetheless, China’s strategy is starting to shift. While still keeping China at the center of its narratives, the fourth-most-popular narrative from Chinese sources focused on the Western response to the virus and Western blame of China, especially from the US. Though still largely avoiding disinformation, China’s destructive and critical narratives about other countries were a departure from its pre-COVID toolkit and a step closer to the Russian playbook.12

China’s ability to effectively respond to COVID-19

At the start of 2020, the CCP’s messaging focused mostly on China and portrayed the country’s fight against COVID-19 in a positive light. When the world’s attention centered on China in January and February 2020, the CCP spread overwhelmingly positive narratives with the goal of making the world feel sympathy for the country suffering from the disease. As the virus began spreading widely beyond China in March 2020, Chinese narratives shifted to focusing on China’s donation of masks and supplies to other countries. Keywords included “supplies,” “assistance,” “aid,” “assist,” and “deliver.” The CCP sought to tell a story that China had defeated the virus at home and was now helping other countries do the same. In Information Bedlam, CEPA found that as early as February 12, 2020, Chinese state media had dropped any mention of Wuhan when talking about the virus’s origins.9 The CCP was already planning for a years-long effort to discredit the international scientific consensus that the virus began in Wuhan in late 2019. Beyond this piece of disinformation, the CCP wanted the world to view China as part of the solution instead of the cause of COVID-19.

China’s assistance to other countries

When Chinese COVID-19 narratives began focusing on China’s assistance to other countries, certain regions took priority, showing China’s use of the pandemic for geopolitical ends. Under Xi Jinping, China has increasingly sought a leading role in the global south, and the pandemic was no exception.13 When amplifying the propaganda that China was helping the world respond to COVID-19, it was no coincidence that South Africa and Ethiopia were prioritized as keywords.

Chinese state media outlets, including newswire Xinhua, have signed content sharing agreements with news outlets in many African countries.14 Africans with internet service have played a significant role in making , Xinhua, China Daily, People’s Daily, and Global Times the five most followed news pages on Facebook.15 It is often cheaper for Africans to access Xinhua than Western newswires. Xinhua may be less sensational and conspiratorial than the state-backed nationalist tabloid Global Times, or Russian outlets like RT and Sputnik, but it frequently leaves out important context on stories ranging from COVID-19 to the Belarusian plane hijacking.16

While Russia tailors existing brands or creates new ones to cater to specific audiences in target countries, Chinese brands’ offerings are largely a reflection of their history within China. Xinhua serves as a newswire akin to, and People’s Daily and China Daily serve as party mouthpieces, Global Times serves as a tabloid while broadcaster CGTN mostly offers the same messaging as People’s Daily and China Daily but in video form. For each, the only receptive audience will be ones already supportive of the CCP, a vanishingly small market. While Chinese production of content outpaces Russia’s, engagement lags far behind.

Criticizing the West for blaming China

By highlighting its own assistance to Africa, China could paint the Western response as self-centered and deliberately neglectful of suffering across the developing world. Own goals by the West helped, such as when French scientists suggested that vaccines should be tested in Africa.17 Nonetheless, China’s top COVID-19 narrative that largely used negative rhetoric focused on Western blame of China instead of the West’s domestic and international response to the virus. This once again showed China’s eagerness to put itself at the center of its narratives and its frantic mission to control information about the virus’s origins and China’s poor initial containment efforts. Keywords included “claim,” “accuse,” “blame,” “attack,” and “rumor.” China’s wolf warrior diplomats went out of their way to criticize any country that dared to question China’s transparency. China even started imposing curbs on some Australian imports after Prime Minister Scott Morrison called for an independent investigation into the virus’s origins.18 China continues to reject any Western blame for its handling of the virus, including renewed attention in May 2021 to the lab-leak theory.19

China’s coverage of the West during COVID-19 was not limited to criticizing Western blame of China. There was significant discussion of deaths from COVID-19 in other countries, most notably Brazil, Italy, Spain, Germany, and the United States. China wanted to show the West’s failure to contain the virus, especially once China had largely brought the virus under control at home. At the same time, China’s coverage of lockdowns and the economic impact from COVID-19 was expressed with slightly more positive sentiment than Russia. Considering early Western criticism of China for its harsh lockdown, China largely avoided denunciations of Western lockdowns. This is in sharp contrast to the incredibly hypocritical Russian media, which regularly criticized the West for taking the same actions as the Russian government while playing up internal divisions around Western culture wars.

Other narratives

While most of the CCP’s COVID-19 narratives were propaganda about China’s success in containing the virus compared with the West’s failures and criticism of China, the party still pushed significant disinformation about the virus’s origins. Since February 2020, the CCP has attempted to change the global narrative on the origins of the virus by taking words out of context from respected scientists in Europe and the US, directing state-backed Chinese scientists to publish papers that put blame for the virus’s origins on other countries, and spreading Russian conspiracies about the virus coming from US military bioweapons labs.20 More recently, China has questioned the efficacy and safety of Western vaccines, even while its own vaccines have not prevented new outbreaks.21 Without targeting messages to specific left- and right-wing audiences, China has not been as critical of vaccines overall as Russia and in 2021 has prioritized messaging about Chinese-produced vaccines.22

V. RUSSIA

Russian propaganda outlets followed “the golden rule of social media marketing” — 80% of content should inform, delight, or entertain, and only 20% should reference the brand — and the most common category of content for Russian outlets publishing in English were simple updates on COVID-19 cases. This base of reliability allowed state media to draw in users for helpful updates, enabling the seamless insertion of content more supportive of Russian goals. With separate brands targeting right-wing and left-wing Anglophones, Russian media could amplify domestic extremists on its widely followed accounts across Twitter, YouTube, and, to a lesser extent, Facebook, aggravating pandemic-induced unrest. Beyond attacking the American response, Russian media and officials looked to portray Russia as a global humanitarian and scientific leader, offering medical relief to countries in need and far outstripping rivals in the race to a vaccine. Nonetheless, domestic disinformation in English-speaking countries often drowned out overt Russian propaganda on COVID-19. This might have reduced the direct impact of Russian IOs, but by seeking to amplify narratives that were already circulating in fringe political ecosystems, long-standing goals of Russian propaganda were achieved, including discrediting American institutions, sparking domestic turmoil, and undermining American democracy.

Create a reliable base of trust on the facts

Russia’s most common COVID-19 content provided only updates on deaths and cases. Total counts and trends generally fell within the mainstream of estimates. Before exaggerating the pandemic’s severity to left-leaning audiences and understating the threat to right-leaning audiences, these narratives laid the foundation to distort and manipulate public opinion by creating a base of trust and establishing Russian outlets as a reliable source of information on COVID-19. This content had a negative sentiment, reflected in the prevalence of words like “death,” “infection,” and “hospitalizations,” and in line with an understandable and near-universal portrayal of the pandemic spread as negative.

Use the established trust to promote extremist political messages

The trust-building content reflects Russia’s sophisticated marketing approach, characterized not just by industry best practices but also by advanced audience segmentation. In both the United States and United Kingdom, all under one RT banner, RT possesses a right-wing brand (RT America, RT UK), mainstream brands with veteran commentators (Larry King, Alex Salmond), and a left-wing brand (Watching the Hawks, Going Underground). Russia has a unique ability to swing across the political spectrum from one show to the next. While the outlets create the lion’s share of their own content, they have long given platforms to American extremists, from avowed fascists to dedicated communists, to amplify existing messages popular on the fringe.

When lockdowns began in March 2020, RT’s conservative outlets portrayed the coming of a totalitarian state, declaring, “Americans won’t stand for it” and warning of “destructive mass protests” as “Western countries that forever preach about the authoritarian impulses of certain foreign states suddenly began to resemble the real autocrats.”23 In line with narratives already circulating in right-wing circles in the US and UK, one RT op-ed claimed lockdown-induced suicides to be a greater threat than the pandemic.24 For left-wing audiences, Watching the Hawks focused on corporate profiteering during the pandemic from Big Pharma, to rumors of landlords exchanging rent for sex from downtrodden tenants, to continued budget expansions for the US military.25

As the American response sputtered, RT highlighted the failings of mostly Democratic governors and gave minimal attention to the federal response. Even on left-wing outlets, criticism of then-President Trump’s response was muted, with the focus instead on the failings of the United States at large and inequities within the health system. Right-wing outlets used the many missteps in the American response to cast doubt on the competence of government responses generally and on the American health care system.

Raise doubt about Western vaccines, promote Sputnik V

The frequency of Russian reporting on COVID-19 case numbers followed broader trends, peaking in spring 2020 and subsiding as cases in the US receded. On June 18, 2020, Russia began Phase I testing for its Sputnik V vaccine and on September 4, Russia announced preliminary results that the vaccine was safe and effective. When an open letter in Lancet questioned the reliability of the Russian results, state media and officials went on the offensive. RT interviewed the scientists behind the vaccine; adopting left-wing criticism, one RT op-ed asked, “Are Western attacks on the Russian Covid-19 vaccine a corporate cold war against humanity?”26 RT then began casting doubt on the safety of Western vaccines, such as AstraZeneca.27 While efforts to inspire trust in Sputnik V gained little traction with audiences and, with the vaccine unavailable to most Anglophone audiences, had little relevance, RT reported breathlessly on side effects from Western vaccines.28 Pfizer continues to receive a disproportionate share of negative coverage, likely because Russia views it as Sputnik’s main competitor.29

Evidence of Sino-Russian coordination?

While the data analysis shows little evidence of direct coordination between Russia and China, the comparative success of China’s COVID-19 response proved a useful foil for Russia’s depiction of Western governments and media. One op-ed declared, “For it seems that locking down around 60 million people in China is tantamount to a gross human rights violation, while doing the same to 60 million Italians is a bold step forward.” An RT report amplified Chinese messaging that “Democracy has seen 500,000 US Covid deaths.”30 Russian reporting on China, while largely positive in its portrayal, for the most part fit into existing Russian campaigns rather than amounting to a directed attempt to improve China’s image. While Russia did not disparage Chinese vaccines, it also didn’t actively promote them, a sign that economic interests still trump circular amplification of propaganda.29

VI. COMPARING AND CONTRASING RUSSIA AND CHINA

One of the biggest misconceptions of 2020 was that China’s IO tactics were increasingly converging with Russia’s. China spread disinformation on a global scale about the origins of the virus and mRNA vaccines, but most of its information operations continued to be biased propaganda with a large focus on China and global narratives about China. Russia’s diverse range of state-backed outlets spread fear among right-wing and left-wing audiences in Europe and North America about lockdowns and Big Pharma’s vaccine development. China’s approach was less nimble, with limited attempts to spread narratives that targeted specific audiences in the West.

Data science techniques revealed Russian actors’ strong emphasis on sentiments more closely associated with fear, in contrast to their Chinese counterparts, who more frequently employed rhetoric associated with trust. This finding supports previous conclusions on how each actor approaches global information operations; while Chinese texts frequently present an internal focus on China’s success conveyed with trust-based rhetoric, the Russian approach tends to employ more fear-mongering tactics and center discussion around the failures of others. In line with China’s prioritization of propaganda over disinformation, sentiment analysis revealed that Chinese narratives were on average more objective than Russian narratives.

While Chinese IOs maintained remarkable consistency among state media, state-backed tabloids like Global Times, and diplomats, the cadence of activity varied dramatically depending on the diplomatic post. In contrast to a coordinated Russian information-warfare strategy, most Chinese embassies in Europe remained relatively quiet about the virus. Exceptions to narrative consistency and relative silence tended to get the most attention, usually negative. For example, when foreign ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian retweeted virus origin disinformation from a pro-Kremlin outlet, at least a dozen Chinese embassies amplified the story along with coverage in several state media outlets.31 Certain wolf warriors were more assertive than typical Chinese narratives, including an unnamed Chinese diplomat in France who blamed the French for letting the elderly die in their nursing homes, yet there was little strategy behind this approach.32 Ambitious diplomats were likely fighting for career advancement instead of serving a broader purpose in China’s IOs. Most Chinese ambassadors act like more typical diplomats and some analysts believe that Xi’s recent call for China to be loved and to speak more softly was effectively a call for diplomats to tone down their rhetoric in the face of potentially irreparable reputational damage.33 At the same time, Xi used provocative language during the CCP’s 100-year anniversary celebrations, potentially undermining any call to soften China’s diplomatic approach.34

While consistency makes it easier for the CCP to control its information space and speak with a unified message, it also undermines its IOs. Even with substantially more resources, by not differentiating its narratives for right- and left-wing audiences, Chinese propaganda fails to move Western public opinion in the way that Russian disinformation does, but China is increasingly adept across the developing world. With its firehose of falsehoods method, which encourages contradictions among channels and within them, Russia is more sophisticated at targeting Western Anglophone audiences. Through this approach, malign Russian narratives more easily enter political conversations across the West. Russia’s goal is to make people believe that the truth can never be known while providing convenient storylines that fit into people’s right-wing or left-wing worldviews.

China on the other hand attempts to tell one story with full certainty, which is much less successful. One exception is Facebook, where China already owns the five most-followed news pages.35 China has also tried to gain prominence with a more traditionally left-wing audience through ideologically communist references to workers’ rights, but this ultimately falls flat because its promotion is primarily focused on the CCP. If China were to target left-wing groups without as clearly supporting the CCP, it could likely have more impact on its audience, which currently engages with Chinese content at abysmal rates.

If China has a geographic strategy in the information environment, it is targeting “unclaimed” audiences, mostly in Africa. It remains to be seen whether this strategy can work, but it does help that Chinese and Russian vaccines were often the first to arrive in the developing world.36 Russia also has a strategy to focus its resources specifically on Latin America, Africa, and the Middle East.37 Analysis from Stanford showed that Russian media in these regions are often less conspiratorial and sometimes even critical of Russia, potentially to spread Russian influence while lending a veneer of credibility and independence to the media outlets that they lack among mainstream audiences across much of the West.38 This has proved relatively successful, with RT en Español’s Twitter engagements outpacing RT by a 2:1 margin.29

One understudied aspect of Chinese and Russian COVID-19 narratives was their promotion of domestic scientific prowess. Sputnik V showed Russian scientific prowess and harkened back to the glory days of Soviet science. While many medical experts were shocked when Russia announced the initial success of Sputnik V before advanced phases of clinical trials, subsequent trials have shown that the vaccine is relatively successful.39 China’s vaccines, on the other hand, have been less effective, with reports frequently surfacing about communities and entire regions being reinfected after receiving them.40 Though Russian messaging around domestic scientific prowess mostly focused on Sputnik V, early in the pandemic, a common Chinese narrative was that traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) could play a key role in defeating the virus.

VII. IMPLICATIONS FOR RESEARCHERS AND POLICYMAKERS

This research and data raise important questions and issues for policymakers across the transatlantic space. Countering malign information operations from Russia and China will require different policy responses in different places correlating to the diverse strategies from Moscow and Beijing. Russia is still better at spreading diverse narratives depending on the target country, but through authoritarian learning and impressive resources, China could copy this page from the Russian playbook. Measuring the impact of authoritarian influence operations is challenging, but Xi Jinping’s recent call for Chinese diplomats to set the “right tone” in diplomatic engagement could be a sign that the CCP is worried about overreach with its wolf warrior diplomacy.41 Western leaders should continue to call out unprofessional and aggressive diplomacy from Moscow and Beijing, which can help drive public opinion of their malign influence operations. Many questions remain, but through data analysis and extensive research of Russian and Chinese IOs, policymakers can get a stronger grasp of the extent of the challenge and best resources to confront authoritarian information warfare.

How do IOs differ across the US, Canada, and Europe?

- Chinese media outlets had largely consistent COVID-19 coverage throughout the West, though the country’s diplomats in certain countries, notably France, were more eager to engage in wolf warrior diplomacy than others. These were likely efforts by Chinese diplomats to advance their careers instead of a sophisticated strategy by China to place the most undiplomatic officials in key posts.42

- Beijing prioritized narratives that would resonate in Africa. The keyword “cold” was used 138 times in tweets over three months to amplify the message that China’s vaccines could be more easily used in the developing world than Western vaccines, which required advanced freezers.29

- Russian messaging was more nuanced throughout the West depending on political circumstances. Within certain countries, especially the US, Germany, and France, Russian narratives were consistently more negative toward left-wing state-level leaders than those on the right.

Are Russian and Chinese information operations coordinated or diverging? If China isn’t following a Russian playbook, what playbook is it following?

- China has borrowed some aspects of the Russian playbook, but the CCP isn’t necessarily following it as closely as researchers believed at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.43

- Beijing is pursuing global information operations with Chinese characteristics, including consistency across messengers, prioritization of narratives that resonate in the developing world, and a greater reliance on propaganda than disinformation.

- Russia’s IOs remain more sophisticated and mature, with China still resorting to cheap amplification networks to manufacture consensus.44

What are specific issue areas that should concern policymakers? Underexplored spaces that Russia and China are filling?

- Researchers have been concerned that China will emulate Russian information-warfare tactics, but in many respects, authoritarian learning flows both ways and Russia is also learning from China. Like China, Russia is increasingly controlling the free flow of information, deepening media partnerships in the developing world, making “goodwill” donations, and spreading the narrative that Sputnik is a public good rather than a for-profit vaccine.

- Both countries are using visual content like memes and cartoons while also recruiting social media influencers to spread their toxic narratives. Content creators and sharers on TikTok and other platforms with millions of followers have worked or continue to work with Russian and Chinese state media.

- While outside the scope of this paper, China is investing heavily in media in Francophone Africa, a region with few competitors and the potential for Chinese content to move public opinion.

- There is little evidence of explicit Sino-Russian coordination in the information environment, but talent sharing between state media is an underexplored threat. There also seems to be growing overlap in the influencers, commentators, and op-ed writers used by Russia and China.

What strategic goals have Russian and Chinese information operations fulfilled? How can we measure impact?

- Measuring impact of Russian and Chinese IOs is challenging, but at least in the developed world, the COVID-19 response from the two authoritarian actors failed to positively sway public opinion.45

- China has more resources than Russia, but its content gets substantially less engagement and has limited impact.

- Russian and Chinese IOs fit with their broader geopolitical goals. Russia seeks to destroy the global order to strengthen its relative power while China selectively undermines the West to increase its absolute power within the existing global order.

VIII. METHODOLOGY

Data collection

The data in this study were collected from March 2020 to March 2021 from the websites and social media accounts of all large Russian and Chinese state-owned broadcasters, government sources, and embassies46 across the globe. Collected in the dataset are all English-language news articles and social media posts these accounts published during this time that contain one or more of the following terms: “COVID,” “corona,” “pandemic,” “lockdown,” or “quarantine.” Reflecting the total number of texts that fit these criteria, there are 144,207 documents in the dataset. Complementing the data is desk research incorporating outside sources, including primary sources from Russia and China, as well as CEPA’s findings from Information Bedlam.

Data preprocessing

All texts were cleaned of stopwords –– common English words that add little thematic meaning to a document –– through use of the Snowball English-language stopword list, included in the RStudio stopwords package. Additional stopwords removed from the texts during topic modeling were those common to most documents in the corpus, including any variation of “COVID” or “corona,” “illness,” “infection,” “virus,” “pandemic,” “epidemic,” “disease,” “outbreak,” and “quarantine.” Additional preprocessing steps included converting all text to lower case and removing numbers and punctuation from the texts.

Building and tuning the model

The 144,207 texts in the dataset were separated into a subset of 89,729 documents published by Chinese actors and another of 54,487 documents published by Russian actors. Individual models were created for each dataset to deduce primary topics unique to each actor’s information operations.

Regarding parameter selection, the LDA (Latent Dirichlet Allocation topic modeling) requires the number of K values or clusters to be specified by the programmer. These models were programmed to identify the top six topics within each of the two sets of texts. These optimal K values were determined by examining model output from a variety of K values and assessing the interpretability of results, in tandem with selecting the K value associated with the highest topic coherence score.

In terms of hyperparameter selection, an alpha value of 0.1 was used in both the LDA model fit to the Chinese texts and its counterpart fit to the Russian corpus. This was selected since it is often regarded as the default alpha value for the LDA model.

Sentiment Analysis Procedure

Using data science methods, researchers scored the texts in each of the identified topics according to the degree to which they contained language associated with subjective vs. objective content and rhetoric conveying the emotions of fear vs. trust.

To measure objectivity, we used the TextBlob library, which can process a text and provide a score indicating whether the document’s content possesses greater features of subjective or objective reporting. In this context, objective material is defined as factual information, while subjective material tends to contain emotion and espouse judgments or personal opinions. This is a lexicon-based approach to natural language processing, meaning the algorithm uses a dictionary containing likely rankings for individual words in order to generate these scores. Each word in a text is granted a ranking, and then these individual scores are combined into a single value, indicating the presence of subjective vs. objective rhetoric in a larger document.

The NRC Word-Emotion Association Lexicon was employed for the fear vs. trust score. This tool also uses a lexicon-based approach to natural language processing wherein words in an English dictionary are ranked based on the degree to which they are associated with eight fundamental emotions: anger, fear, anticipation, trust, surprise, sadness, joy, and disgust. This dictionary is then used to assess whether an entire text contains rhetoric associated with these eight emotions and in this case focused on fear and trust.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Jabbed in the Back is part of a broader CEPA research project aimed at tracking and evaluating Russian and Chinese information operations around COVID-19. This report complements Information Bedlam, a report published in March 2021 examining the pre-existing literature on Russian and Chinese COVID-19 information operations. Future analysis will examine the efficacy of policy responses and provide actionable recommendations for transatlantic decision-makers. This work benefited research and data analysis support from former Research Assistant Mallie Kermiet, as well as feedback from a working group of experts and practitioners, convened by CEPA, working on Russian and Chinese information operations. A special thanks to Bret Shafer for his thoughtful feedback. This work was made possible with the generous support of the Smith Richardson Foundation.

By Ben Dubow, Edward Lucas, Jake Morris, for CEPA

- Christopher Paul and Miriam Matthews, “Russia’s ‘Firehose of Falsehood’ Propaganda Model,” RAND Corporation, July 11, 2016, https://www.rand.org/pubs/perspectives/PE198.html.

- Edward Lucas, Jake Morris, and Corina Rebegea, “Information Bedlam: Russian and Chinese Information Operations During Covid-19,” Center for European Policy Analysis, March 15, 2021, https://cepa.org/information-bedlam-russian-and-chinese-information-operations-during-covid-19/.

- CEPA worked with Omelas to collect the data; see endnotes throughout the paper for complementary research from other think tanks and academic institutions.

- Liz Alderman, “Influencers Say They Were Urged to Criticize Pfizer Vaccine,” The New York Times, May 26, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/26/business/pfizer-vaccine-disinformation-influeners.html?referringSource=articleShare.

- Sheera Frenkel, Maria Abi-habib, and Julian E. Barnes, “Russian Campaign Promotes Homegrown Vaccine and Undercuts Rivals,” The New York Times, February 5, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/05/technology/russia-covid-vaccine-disinformation.html.

- Samuel Brazys and Alexander Dukalskis, “China’s Message Machine,” Journal of Democracy (Johns Hopkins University Press, October 8, 2020), https://muse.jhu.edu/article/766184.

- Alana Wise, “Biden Asks U.S. Intel to Push for Stronger Conclusions on the Coronavirus’ Origins,” NPR, May 26, 2021, https://www.npr.org/2021/05/26/1000642995/biden-asks-u-s-intel-to-push-for-stronger-conclusions-on-the-coronavirus-origins.; Katerina Ang and Adam Taylor, “As U.S. Calls for Focus on COVID ORIGINS, China REPEATS Speculation about U.S. Military Base,” The Washington Post (WP Company, May 27, 2021), https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2021/05/27/virus-china-fort-detrick/; “Online Petition for Fort Detrick Probe Draws 20m Signatures; China Urges US to Open UNC Lab, Disclose Military Games Patients,” Global Times, July 30, 2021, https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202107/1230123.shtml.

- Sarah Cook, “Beijing’s Coronavirus Propaganda Has Both Foreign and Domestic Targets,” Freedom House, April 20, 2020, https://freedomhouse.org/article/beijings-coronavirus-propaganda-has-both-foreign-and-domestic-targets.; Gerry Shih, “China Turbocharges Bid to Discredit Western Vaccines, Spread VIRUS Conspiracy Theories,” The Washington Post (WP Company, January 20, 2021), https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/vaccines-coronavirus-china-conspiracy-theories/2021/01/20/89bd3d2a-5a2d-11eb-a849-6f9423a75ffd_story.html.

- Lucas et al, “Information Bedlam”

- “Viral Overload,” Omelas, May 12, 2020, https://www.omelas.io/viral-overload.

- Jessica Brandt and Bret Schafer, “Five Things to Know About Beijing’s Disinformation Approach,” Alliance For Securing Democracy (German Marshall Fund of the United States, March 30, 2020), https://securingdemocracy.gmfus.org/five-things-to-know-about-beijings-disinformation-approach/.

- Daniel Kliman et al., “Dangerous Synergies: Countering Chinese and Russian Digital Influence Operations,” Center for a New American Security, May 7, 2020, https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/dangerous-synergies.

- David O Shullman, “Protect the Party: China’s Growing Influence in the Developing World,” Brookings, January 22, 2019, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/protect-the-party-chinas-growing-influence-in-the-developing-world/.

- Sarah Cook, “Beijing’s Global Megaphone: The Expansion of Chinese Communist Party Media Influence Since 2017,” Freedom House, January 15, 2020, https://freedomhouse.org/report/special-report/2020/beijings-global-megaphone#footnote28_6sjbbeq.

- “China Is Using Facebook to Build a Huge Audience around the World,” The Economist (The Economist Newspaper, April 20, 2019), https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2019/04/20/china-is-using-facebook-to-build-a-huge-audience-around-the-world.; “Top 100 Facebook PAGES Sorted by Likes,” Social Blade, 2021, https://socialblade.com/facebook/top/100/likes.

- Brazys and Dukalskis, “China’s Message Machine”; Hua Xia, ed., “EU Leaders Condemn Ryanair Flight’s Diversion to Belarus,” Xinhua, May 24, 2021, http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2021-05/24/c_139965507.htm.

- “Covid-19 Disinformation & Social Media Manipulation,” Australian Strategic Policy Institute, October 27, 2020, https://www.aspi.org.au/report/covid-19-disinformation.

- “Timeline: Tension between China and Australia over Commodities Trade,” Reuters (Thomson Reuters, December 10, 2020), https://www.reuters.com/article/us-australia-trade-china-commodities-tim/timeline-tension-between-china-and-australia-over-commodities-trade-idUSKBN28L0D8.

- James Palmer, “Why Beijing Will Never Cooperate with a Covid-19 Investigation,” Foreign Policy (The Slate Group, June 9, 2021), https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/06/09/china-cooperate-covid-19-origins-investigation-wuhan/.

- Vanessa Molter and Graham Webster, “Virality Project (China): CORONAVIRUS Conspiracy Claims,” Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies (Stanford University, March 31, 2020), https://fsi.stanford.edu/news/china-covid19-origin-narrative.; Lucas et al, “Information Bedlam”; Kliman et al, “Dangerous Synergies”

- Sui-lee Wee, “They Relied on Chinese Vaccines. Now They’re Battling Outbreaks.,” The New York Times, June 22, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/22/business/economy/china-vaccines-covid-outbreak.html.; “Why Were US Media Silent on Pfizer Vaccine Deaths?: Global Times Editorial,” Global Times, January 15, 2021, https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202101/1212939.shtml.

- Bret Schafer et al., “Influence-Enza: How Russia, China, and Iran Have Shaped and MANIPULATED Coronavirus Vaccine Narratives,” Alliance For Securing Democracy (German Marshall Fund of the United States, March 6, 2021), https://securingdemocracy.gmfus.org/russia-china-iran-covid-vaccine-disinformation/.

- “’Americans Won’t Stand FOR It’: Outrage and Protests as Mother Arrested for Letting Children Play in Park,” RT International, April 22, 2020, https://www.rt.com/usa/486589-mother-arrested-idaho-playground-protests/.; Robert Bridge, “’Open the Economy – i Need to Feed My Family!’ Will Lockdown Fatigue Spiral into Destructive Mass Protests?” RT International, April 22, 2020, https://www.rt.com/op-ed/486579-covid-19-lockdown-destructive-economy/.

- Helen Buyniski, “Deadlier than Covid? Medics Sound Alarm As Lockdown SUICIDES Soar in US – and Health Officials Knew It Would Happen,” RT International, May 23, 2020, https://www.rt.com/op-ed/489584-covid-lockdown-suicide-deaths/.

- Nurse Exposes Covid Hospital Controversies & US-China Tensions Rising, YouTube (Watching the Hawks RT, 2020), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1N5nWYQp9_k.; Covid-19: Bailouts For The Rich, Suffering For The Poor, YouTube (Watching the Hawks RT, 2020), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y9l2ci8M3cs.; “This Holiday Season While Restaurants, Schools, and Businesses Close across the U.S. Thanks to the Covid-19 Pandemic, the U.S. Military Industrial COMPLEX Remains Open for Business,” Twitter (Watching the Hawks RT, November 20, 2020), https://twitter.com/WatchingHawks/status/1329820261626114049.

- Kirill Dmitriev, “Sputnik V Questions ANSWERED: Head of Team FINANCING World’s FIRST COVID-19 Vaccine Explains Formula to Critics,” RT International, September 7, 2020, https://www.rt.com/russia/500087-worlds-first-covid-19-vaccine-questions/.; Marcello Ferrada de Noli, “Are Western Attacks on the Russian COVID-19 Vaccine a Corporate Cold War against Humanity?,” RT International, September 17, 2020, https://www.rt.com/op-ed/500981-sputnik-v-cold-war-covid/.

- “Second AstraZeneca Volunteer Reportedly Suffers Rare Neurological Condition, but UK Company Says It’s Not Related to Vaccine,” RT International, September 20, 2020, https://www.rt.com/news/501221-astrazeneca-vaccine-neurological-condition/.

- The Moscow Times, “Majority of Europeans Don’t Trust Russia’s CORONAVIRUS Vaccines – Poll,” The Moscow Times, June 10, 2021, https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2021/06/10/majority-of-europeans-dont-trust-russias-coronavirus-vaccines-poll-a74179.; “’We See Nothing Alarming,’ Says Norwegian Drugs Regulator, after 13 Deaths Linked to Pfizer VACCINE Jabs,” RT International, January 15, 2021, https://www.rt.com/news/512586-norway-vaccine-elderly-deaths/.; “51 Adverse Reactions Reported & 1 Person Hospitalized in Delhi as INDIA Begins World’s Largest Covid-19 Vaccination Program,” RT International, January 17, 2021, https://www.rt.com/news/512774-india-adverse-effects-covid-vaccine/.; “Sweden Records 30,000 Suspected Side Effects FROM Covid Vaccines, with Astrazeneca’s Jab Linked to More than Half of All Reports,” RT International, May 12, 2021, https://www.rt.com/news/523566-vaccine-side-effects-sweden-astrazeneca/.

- Schafer et al, “Influence-enza”

- “Democracy Has Seen 500,000 Us Covid Deaths: China Hits Back as Biden Says Xi Jinping ‘Doesn’t Have a DEMOCRATIC Bone in His Body’,” RT International, March 26, 2021, https://www.rt.com/news/519255-china-biden-democracy-values-covid19/.

- Brandt and Schafer, “Five Things to Know”

- “China Hopes France Removes Misunderstandings, Cooperates against Virus,” CGTN, April 15, 2020, https://news.cgtn.com/news/2020-04-15/China-hopes-France-removes-misunderstandings-cooperates-against-virus-PI8GgBN0Ig/index.html.; John Irish, “Outraged French Lawmakers Demand Answers on ‘Fake’ Chinese Embassy Accusations,” Reuters (Thomson Reuters, April 15, 2020), https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-france-china/outraged-french-lawmakers-demand-answers-on-fake-chinese-embassy-accusations-idUSKCN21X30C.

- “Xi Jinping Calls for More ‘Loveable’ Image for China in Bid to Make Friends,” BBC News (BBC, June 2, 2021), https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-57327177.

- There has been some debate over whether the literal translation of Xi’s remarks was correct, which could change the tone of his remarks.

- “China Is Using Facebook to Build a Huge Audience around the World,” The Economist (The Economist Newspaper, April 20, 2019), https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2019/04/20/china-is-using-facebook-to-build-a-huge-audience-around-the-world.; “Top 100 Facebook PAGES Sorted by Likes ,” Social Blade, 2021, https://socialblade.com/facebook/top/100/likes.

- Alexander Smith, “Russia and China Are Beating the U.S. at Vaccine Diplomacy, Experts Say,” NBCNews.com (NBCUniversal News Group, April 2, 2021), https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/russia-china-are-beating-u-s-vaccine-diplomacy-experts-say-n1262742.

- Renée DiResta et al., “Telling China’s Story: The Chinese Communist Party’s Campaign to Shape Global Narratives,” Cyber Policy Center (Stanford Internet Observatory, July 21, 2020), https://www.hoover.org/research/telling-chinas-story-chinese-communist-partys-campaign-shape-global-narratives.

- Daniel Bush, “Two Faces of Russian Information Operations: Coronavirus Coverage in Spanish,” Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies (Stanford University, July 30, 2020), https://fsi.stanford.edu/news/two-faces-russian-information-operations-coronavirus-coverage-spanish.

- Bianca Nogrady, “Mounting Evidence Suggests Sputnik COVID Vaccine Is Safe and Effective,” Nature News (Nature Publishing Group, July 6, 2021), https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-01813-2.

- Paul Schemm and Adam Taylor, “China’s Great Vaccine Hope, Sinopharm, Sees Reputation Darkened amid Covid Spikes in Countries Using It,” The Washington Post (WP Company, June 3, 2021), https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2021/06/03/bahrain-seychelles-sinopharm-vaccine/.

- Steven Lee Myers and Keith Bradsher, “China’s Leader Wants a ‘Loveable’ Country. That Doesn’t Mean He’s Making Nice.,” The New York Times, June 8, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/08/world/asia/china-diplomacy.html.

- Bonnie S Glaser, “China’s Wolf Warrior Diplomacy: A Conversation with Peter Martin,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, June 7, 2021, https://www.csis.org/podcasts/chinapower/chinas-wolf-warrior-diplomacy-conversation-peter-martin.

- Jessica Brandt and Torrey Taussig, “The Kremlin’s Disinformation Playbook Goes to Beijing,” Brookings, May 19, 2020, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2020/05/19/the-kremlins-disinformation-playbook-goes-to-beijing/.; Bethany Allen-Ebrahimian, “China Adopts Russia’s Disinformation Playbook,” Axios, March 25, 2020, https://www.axios.com/coronavirus-china-russia-disinformation-playbook-c49b6f3b-2a9a-47c1-9065-240121c9ceb2.html.

- Raymond Serrato and Bret Schafer, “Reply All: Inauthenticity and Coordinated Replying in pro-Chinese Communist Party Twitter Networks,” Institute for Strategic Dialogue, August 6, 2020, https://www.isdglobal.org/isd-publications/reply-all-inauthenticity-and-coordinated-replying-in-pro-chinese-communist-party-twitter-networks/.

- Laura Silver, Kat Devlin, and Christine Huang, “Unfavorable Views of China Reach Historic Highs in Many Countries,” Pew Research Center’s Global Attitudes Project (Pew Research Center, October 6, 2020), https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2020/10/06/unfavorable-views-of-china-reach-historic-highs-in-many-countries/.; Christine Huang, “International Opinion of Russia and Putin Remains Negative in 2020,” Pew Research Center, December 16, 2020, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/12/16/views-of-russia-and-putin-remain-negative-across-14-nations/.

- Please note that the tweets data only includes tweets from embassies and does not include tweets from diplomats. Analysis on diplomats is drawn from other sources.