By RuNet Echo, for Global Voices

Today, Russia’s State Duma passed the third and final reading of a new bill expanding the scope of the country’s controversial “foreign agent” law.

The first iteration of the law appeared in 2012, and introduced the term “foreign agent” to refer to NGOs which receive foreign funding. It’s a loaded term in Russian, with strong associations with espionage. In November 2017, mass media organisations got to labelled “foreign agents” if they received funding from overseas; the move came soon after the state-funded news outlet RT was made to register as a “foreign agent” by the United States authorities. Since then, several organisations have been declared “foreign agents” by the Russian authorities, such as the Anti-Corruption Foundation of opposition politician Alexey Navalny in October 2019.

The latest amendments expand the definition of “foreign agent” to individuals, at the discretion of the Ministry of Justice, which already maintains online lists of “foreign agent” media outlets and NGOs. They also oblige any media organisation recognised as a “foreign agent” to first establish a Russian legal entity in order to operate in the country, and require individuals to publicly state this status and submit to intense financial reporting requirements. The punishments for non-compliance are harsh, including prison sentences of up to two years and fines of up to five million rubles (around 80,000 USD). On November 18, 10 international NGOs signed an open letter denouncing the new bill as a serious threat to freedom of expression in Russia.

How do the Russian authorities know a “foreign agent” when they see one?

The text of the new amendments, added to the federal laws on information and telecommunications, do not suggest any consistent criteria. Foreign agents, it reads, are “individuals disseminating printed, audiovisual, or other messages and material (including by use of the internet) intended for a potentially unlimited circle of people, receiving money and (or) other property from foreign states, their institutions, international and foreign organisations, foreign citizens, stateless individuals and their agents, and (or) Russian legal entities who receive money and (or) other property from indicated sources.”

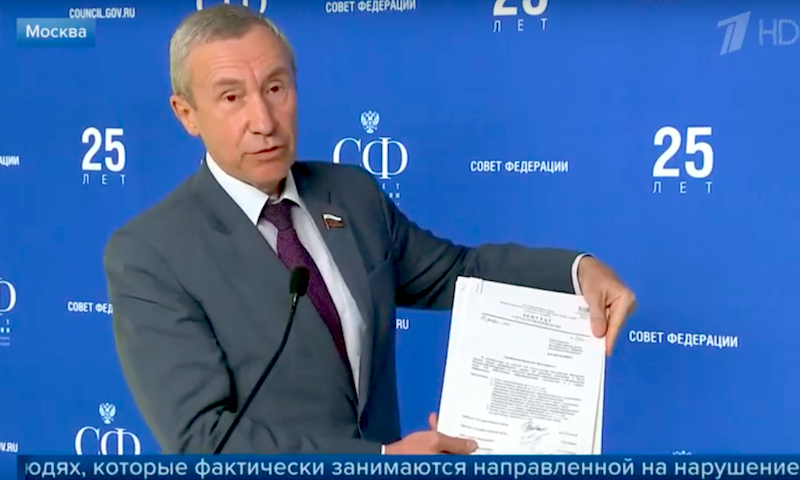

State officials have stressed that the new law is nothing to worry about. On November 12, Andrei Klimov, chairman of the Federation Council’s commission for protecting state sovereignty and a staunch defender of the “foreign agent” laws, told the state news agency TASS that “the new law differs from the old one only in its detail,” and emphasised that somebody wouldn’t become a “foreign agent” simply for receiving an international payment. It would require “constant collaboration” with organisations already recognised as foreign agents, explained Klimov. “In my opinion, this will affect 20-30 people across Russia,” he said. In comments to the government’s official newspaper Rossiyskaya Gazeta in October, Klimov stressed that the law “would not affect people who write something to each other on social media,” and justified its implementation by reference to the case of Maria Butina, the Russian citizen deported from the US on charges of working as a “foreign agent” for Moscow.

But on November 13, Leonid Levin, the chairman of the State Duma’s committee on information policy and communications, told TASS that journalists working for media outlets considered “foreign agents” could find themselves branded “foreign agents” too if their work covers “the socio-political situation.” Klimov also confirmed in the same article that political activity would be the qualifying factor.

Many bloggers and journalists, particularly those in independent and opposition media, are wondering where the new law leaves them. Aleksandr Plyushchev, a popular blogger and talk show host at the radio station Ekho Moskvy, reflected on the chilling effect of the law on his Telegram channel:

Concerning the law which was basically adopted today on citizens as foreign agents. It’s a very unusual feeling when the authorities of your home country draft and pass an entire law aimed explicitly at yourself. Well, not only at yourself, but yourself as part of a particular, and by no means small, group of people.

We are all subject to various laws, but the prospect of your name and surname ending up on a special list is something quite different. It is unlikely that those who fell under personal sanctions in connection, say, with the Magnitsky Act or due to the Donbas feel quite the same; in those cases, a foreign state is acting against you, and here, it’s one’s own country.

So now, we know how it is with silver, now let’s see what it’s like with acid. [a reference to a song by popular Russian band Akvarium]

— Aleksandr Plyushchev, Telegram, November 19, 2019

Mika Velikovskiy, a journalist working for independent newspaper Novaya Gazeta, emphasised that the vagueness of the law posed a threat to ordinary Russians:

If you look at the text of the law, you’ll discover that likes and reposts of media items from foreign agents [are one way to fall foul of it.] But that’s only part of the charm, and only one way to end up on the “foreign agent” list yourself. Any citizen who disseminates information to a potentially unlimited circle of people (which is, in general, everybody on social media networks) or anybody who receives anything from foreigners (not only money) can be recognised as a “foreign agent.” These two criteria are key: the dissemination of information, and anything connected with foreigners (or from a Russian legal entity which has contact with them.) Strictly speaking, almost every Russian falls under this definition. For example, maybe you have a VKontakte profile, and your employer imports diapers? That’s all. Nothing else is required.

— Mika Velikovskiy, Facebook, November 19, 2019

Dmitry Kolezev, the blogger and editor-in-chief of Yekaterinburg-based independent news website Znak, lamented what he called a “nationalisation of intellectuals,” arguing that the law would make Russians warier of travelling abroad or communicating with foreigners, thus isolating Russia’s commentariat and journalists. Its repercussions would reach far more than 20 or 30 people, he warned:

Will life for foreign agents become unbearable? Seemingly not. They will be obliged to label their publications as such (which is demeaning, of course) and file declarations about their income. In that sense, [Duma] deputies want bloggers and journalists to operate by the same rules as state officials and elected representatives. But in doing so, they forget that independent journalists and bloggers have not been granted any authority and do not receive a salary from the state, so it’s not fully understood on what basis the same transparency is demanded of them as from parliamentarians. However, we don’t know what other means of discrimination against “foreign agents” the authorities will come up with in future. Will they have to check in with the Ministry of Justice, will they be forbidden from holding state positions, or will they be forbidden from standing in elections? It could be anything.

— Dmitry Kozelev, Telegram, November 14, 2019

These laws come at a highly charged time in Russian society, following mass protests in Moscow and the institution of a “sovereign internet.” Accordingly, there are indications that new laws concerning freedom of expression are starting to irritate many Russians. A poll taken by the Levada Center in October 2019 and released on November 20 showed that the percentage of Russians who believe that freedom of speech is one of the most important of all rights for citizens rose from 34 per cent to 58 per cent over the last two years.

Amid heated discussion about the law online, the meme “но иностранный агент все равно ты” (but still, you’re the one who’s the foreign agent) has resurfaced. It’s a popular retort in light of regular revelations about Russian officials’ luxury real estate in Europe. For example, Alexey Navalny’s latest investigative video, concerning the Montenegro property of Moscow’s general prosecutor Denis Popov, was entitled “the secret life of a foreign agent.”

Foreign agents and residents are fighting against the “foreign agents” and residents of Ryazan and Novosibirsk.

Essentially, they’re right: we are foreign to them, living in territories where they might as well go on safari. We are Russia’s foreign agents, who happen to live in Russia. What a stunner.

For now, the RuNet is waiting to see who will be first to be branded a “foreign agent,” and what is in store for the person who receives that unfortunate distinction.

By RuNet Echo, for Global Voices