Last week we wrote about the recent wave of disinformation on sanctions. Sanctions, or in EU jargon – restrictive measures, are part of the toolbox countries have to impose costs on other (non-)state-actors spreading disinformation. Why does spreading disinformation remain an attractive option for interference in the information space and how to disrupt this? We present an overview of recent research answering these questions.

Disinformation – Low Cost, Low Risk and High Rewards

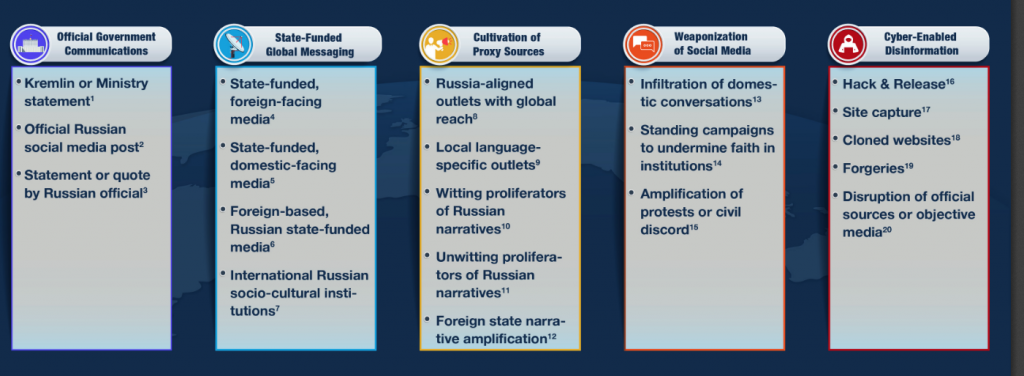

How should one make sense of the infrastructure producing disinformation? Last August, the Global Engagement Center (GEC) at the U.S. Department of State, mandated to expose and counter threats from malign actors that utilize disinformation tactics, provided a useful framework. It defined Russia’s disinformation and propaganda ecosystem as:

the collection of official, proxy, and unattributed communication channels and platforms that Russia uses to create and amplify false narratives.

Consequently, it concluded this ecosystem consists of five pillars: official government communications, state-funded global messaging, cultivation of proxy sources, weaponization of social media, and cyber-enabled disinformation.

Source: GEC, August 2020, report, Five Pillars of Disinformation

The Kremlin bears direct responsibility for cultivating these pillars as part of its approach to using information as a weapon. It invests massively in its propaganda channels, its intelligence services and its proxies to conduct campaigns featuring both malicious cyber activity and disinformation. The Pro-Kremlin ecosystem also leverages outlets that masquerade as news sites or research institutions to spread false and misleading narratives.

Last September, we wrote that the Russian draft federal budget for 2020 promised 92 billion rubles (1.3 billion euros) in subsidies to state controlled media. The single biggest beneficiary of these media subsidies was the TV news channel RT, which received almost 23 billion rubles (325 million euros). This is, of course, a lot of money. However, if it buys a disinformed, disunited and nervous Western alliance, for the Russian Federation it is a bargain, a bookkeeper’s dream.

Because spreading disinformation has relatively low reputational or financial costs and few risks, many experts propose that democracies take measures to impose extra costs on the spreaders of disinformation. James Pamment (Carnegie Peace Endowment) advises the EU to design interventions to influence the calculus of adversary actors. Similarly, the Center for European Policy Analysis recommends democracies to raise the costs for the purveyors of disinformation and the regimes that sponsor and direct them, which might change their incentive risk calculus.

European Democracy Action Plan

The European Democracy Action Plan, published on 3 December 2020, recognizes the need to alter the cost-benefit calculus of perpetrators. How to do this? In foreign affairs terms: by developing EU’s toolbox and new instruments for countering foreign interference in the information space and influence operations. Currently, the EU explores new possibilities to impose costs on the perpetrators, in full respect of fundamental rights and freedoms.

But what does the Other Side Thinks are Costs?

Influence follows understanding. If one wants to influence someone’s cost-benefit calculus one needs to know, what does he understand as costs?

A paper of Keir Giles that came out this month dealt with this question related to Russia. According this research, Russian goals and methods are regarded by many in the West as self-defeating, although they actually achieve acceptable results according to Moscow’s own calculus. This gap often arises because Russia is operating within an entirely different framework of statecraft and assumptions about international relations from Western liberal democracies.

Building on a few cases, Mr Giles describes how Western analyst, looking through a liberal democratic prism, fail to see the importance of collectivist statecraft when perceiving Russia. They do not grasp the strength of the ideal of “the nation”. In the case of Syria, the study shows, while Russia’s military operations created new humanitarian issues and risked the lives of Russian soldiers in ways a western country would not lightly do, it was successful domestically. Western powers are now forced to take Russia into consideration as they move to draw up policies on Syria’s future. This is what matters. For the Russian regime, the benefits of being a power broker is more valuable than the costs of humanitarian issues or the highs risks for the lives of soldiers.

On the benefits side, Mr Giles reminds us of a harsh reality. In the early days of large-scale disinformation campaigns, many thought disinformation was used to achieve distinct political goals. However, Mr Giles point outs that, if you think of what is seen as normal in the information space in 2020 compared to 2015, you see pro-Kremlin disinformation has accelerated trends of fragmentation, distrust, and the spawning of alternative realities. Moreover, it is joined by a wide range of foreign and domestic imitators.

Establishing Norms Against Disinformation

Sanctions might also help to establish norms regarding disinformation. A study of the Hague Centre for Strategic Studies shows the value of norms. Potentially, they are important geopolitical tools. The dynamic character of norms makes them a more flexible and faster alternative than binding law. Yet, they can be an instrument to establish predictability and signal international consensus on what constitutes bad behaviour.

What are the conditions for establishing norms? According to the HCSS study, “Habit and repetition alone – particularly when they go unchallenged…” This has two implications. First, if one wants to establish a norm against disinformation, one has to respond consistently. Second, and this is slightly more alarming, if the spread of disinformation goes unchallenged, apparently, the norm already is that this is allowed.