Over the last few years Kazakh Russian relations have undergone an unprecedented transformation. Losing control over a former Soviet republic and its main Central Asian partner, the Kremlin has pulled out all its imperial tools trying to keep Kazakhstan in its orbit. The protests which began on January 2 and the rapid introduction of Collective Security Treaty Organization troops into Kazakhstan have shown quickly and uncompromisingly that Moscow is ready to fight for its influence in Central Asia. This article traces the history of relations between Russia and Kazakhstan in recent years and identifies the tools the Kremlin uses to maintain leverage in this country.

For many years Kazakhstan has been a loyal Kremlin partner. Like Belarus, Kazakhstan joined Moscow’s Customs Union and in 2014 the country signed the Eurasian Economic Union treaty. However, Kazakhstan’s full-scale integration with Russia into a single economic space began to falter towards the end of former Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev’s rule. Political disparities began to emerge then and after the 2014 Russian annexation of Crimea, Kazakh pro-Russian sympathies cooled considerably. And for good reason.

In the past few years Russian politicians and members of parliament have publicly questioned Kazakhstan’s territorial integrity and the number of negative stories about the country in Russian media have markedly increased. Russian President Vladimir Putin has openly spoken about the lands of its neighbors as “generous gifts from the Russian people”. In 2014 Putin declared that prior to the Nazarbayev presidency, “Kazakhs never possessed statehood”. After Ukraine’s Maidan protests Kazakhstan began to combat separatism within the country more actively. Social media networks began to block communities linked to Russia, pro-Russian blogger Yermek Taichibekov was sentenced to seven years in prison for “inciting ethnic hatred” and blogger Igor Sychov was jailed for separatism.

In anticipation of possible provocations from the Russian Federation, Kazakhstan also tried to limit Russia’s cultural influence in the country: it pursued a course to Latinize the Kazakh language and weaken the role of the Russian language in public life. Kazakh authorities also restricted the broadcasting of some Russian TV channels. On the one hand, Kazakhstan, along with Belarus are post-Soviet countries with the highest level of Russian language proficiency (it is estimated that about 80% of the country’s population speaks Russian). But on the other hand, the demographic changes of the last 30 years have led to a decrease in the number of Russians in Kazakhstan and an increase in the number of ethnic Kazakhs – they make up 66% of the population.

Realizing that Kazakhstan was gradually slipping away, in late 2019 the Kremlin began to increase tension with statements about territorial claims and the alleged “oppression of Russian speakers” in Kazakhstan. August 2021 saw the publication of stories about the so-called language patrols in Russian media. Such stories claimed that Russian speakers were forced to publicly apologize for speaking Russian and that patrols were monitoring the use of Kazakh in shops and government offices. Gazeta.ru, wrote about an alleged attack on a child in Taraz motivated by language intolerance. Argumenty I Fakty cried “Why have so many pseudo-patriots become so brazen in Central Asia?”. Similar publications and videos even found their way into Ukraine’s information space through Russian language telegram channels and social media.

This has not passed unnoticed at the highest levels in Russia. The “Kazakh issue” began to be mentioned regularly at Russian Foreign Ministry briefings. Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova assured that Russia is “united with the leadership of Kazakhstan” and “any manifestations of nationalism will be stopped decisively”. Yevgeny Primakov, the head of Rossotrudnichestvo (Federal Agency for the Commonwealth of Independent States Affairs, Compatriots Living Abroad, and International Humanitarian Cooperation) called on Kazakhstan to take measures against “Russophobes”. Russia’s Federation Council issued its assessment of the “nationalists” in Kazakhstan. In the end Kazakh President Tokayev had to explain what the Russian language meant for Kazakhstan: “Russian has an official language status, according to our legislation, its use cannot be hindered”. He also called for “zero tolerance for ethnic conflicts.” Meanwhile, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov noted that xenophobia against Russian-speakers in Kazakhstan was being orchestrated from the outside: “Some cases are largely the product of special information methodologies being applied from outside, aimed at cultivating urban nationalism and discrediting cooperation with Russia“. Thus, the Kremlin used its favorite narrative of “provocations by Western intelligence services” and “oppression of the rights of the Russian-speaking population” in Kazakhstan.

The process of demarcating the boundary between Kazakhstan and Russia is ongoing and this is regularly reported by Russian media. This, despite the fact that the border agreement was signed and ratified by both countries in 2005. The border between Kazakhstan and the Russian Federation is some 7.500 kilometers long, it is the longest land border in the world. That is why statements by Russian parliamentarians laying claim to Kazakh territory had such resonance in Kazakh society.

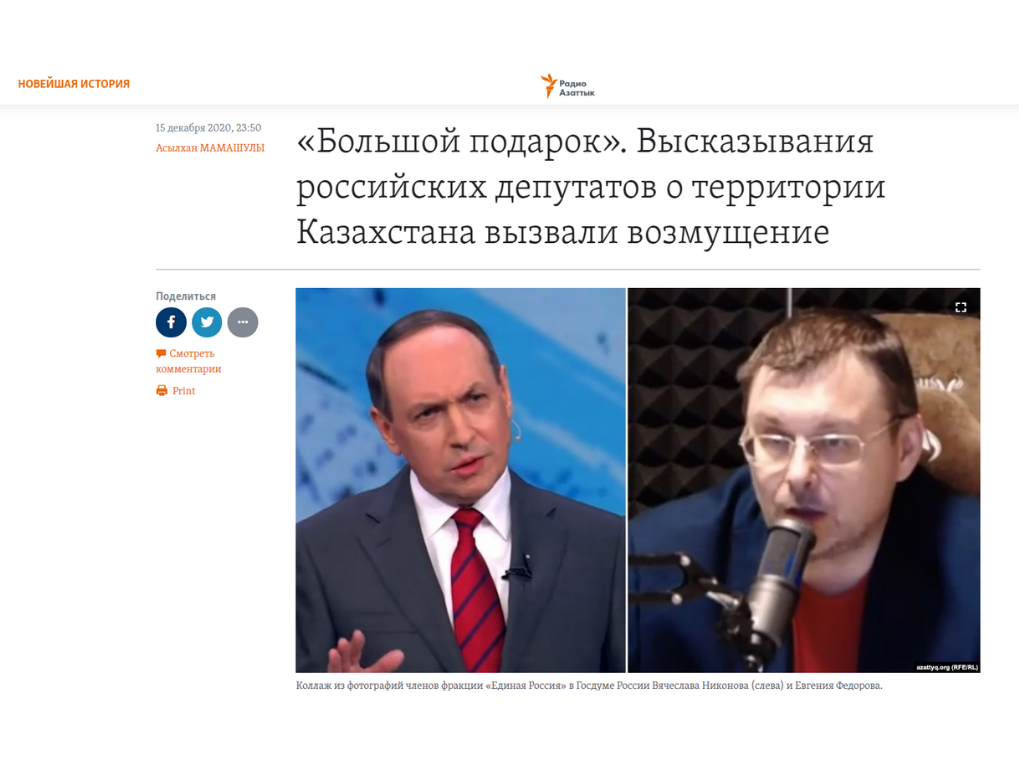

Appearing on Russian state television in December 2020, Russian MP Vyacheslav Nikonov announced that Kazakhstan was a newfangled creation: “Kazakhstan simply did not exist, northern Kazakhstan was not inhabited at all and today’s Kazakhstan is a great gift from Russia and the Soviet Union”. Another MP, Yevgeny Fedorov echoed Nikonov’s opinion, claiming that if Kazakhstan believed that it did not receive “gifts” from Russia and the USSR, then it must be treated differently. The Kazakh Foreign Ministry reacted decisively to these statements, making it clear it was not ready to put up with them.

President Tokayev even published an article in the magazine Sovereign Kazakhstan in which he wrote: “Our sacred land, inherited from our ancestors, is our greatest wealth. It was not gifted to us by anyone. Domestic history did not begin in 1991 or 1936. ” But Russian media continued adding fuel to the fire, reporting that condoning developments in Kazakhstan could result in “an aggressive Turkic belt outside Russia, creeping into the Volga region, Yakutia, and the North Caucasus. And then the dreams of enemies about “Russia within the Moscow principality” will begin to come true. ” Komsomolskaya Pravda accused Kazakh elites of deliberately expelling Russian-speakers from northern Kazakhstan cities and towns and of by squeezing out the the Russian language with increased use of Kazakh.

Another point of contention between Kazakhstan and the Kremlin was Kazakhstan’s principled stand on not recognizing Crimea as Russian territory after Moscow occupied the Ukrainian peninsula in 2014. President Tokayev would not call the Russian takeover of Crimea an annexation. The Foreign Ministry of Kazakhstan only noted that it accepted the Crimean referendum “with understanding”, a referendum that Russian occupying forces held at the barrel of a gun and used as justification for their occupation. Kazakhstan also refused to join Russia’s counter sanctions against Western countries, arguing that “Western sanctions are based primarily on political motives and directed against individual states, not the entire Eurasian Economic Union.” This stance also did not go unnoticed by the Kremlin.

Russia did all it could to maintain its control in Asia. But without Kazakhstan, it was impossible to imagine either the Eurasian Economic Union or the Collective Security Treaty Organization, in both of which Russia is dominant. Since the start of the war in Ukraine, the Kremlin has consistently criticized the Kazakh government for its alleged “rapprochement with the West.” But Kazakhstan’s gradual rapprochement with Turkey, which came to Central Asia with the idea of uniting the Turkic world, was even more alarming for Russia. In order to bind Kazakhstan closer to Russia, an updated Agreement on Military Cooperation between the two countries was signedv in October 2020 during a meeting of the two countries’ defense ministers. The fact that Kazakhstan, which has strong ties to both the United States and China, found it increasingly difficult to stand aside from the large-scale geopolitical conflict that Russia unleashed in Ukraine.

Russia has not even been able to become an attractive investment partner for Kazakhstan, despite both countries having a similar resource base. In 2019 the oil sector, estimated to account for 44% of Kazakhstan’s state budget, saw 30% of the market go to American companies, Chinese companies had approximately% 17% of the sector and Russian companies a very modest 3%. From 2005-2018 Russia was not the investment leader in Kazakhstan’s economy. Gazeta.ru lamented that Russia is losing Kazakhstan, pointing out the high volume of Western investment compared to Russia’s very modest one.

Over the last two years Russia has changed from being Kazakhstan’s strategic partner into a threat, and the Kremlin’s constant provocations have turned a portion of Kazakh society against Russia. In order to bring Kazakhstan back under its wing, Russia will use its full arsenal of propaganda and provocations that it honed in Ukraine and Belarus.

The Russian Foreign Ministry has already stated that it views the protests in Kazakhstan as “an externally inspired attempt to undermine the security and integrity of the state by force, using prepared and organized armed groups.” These are parallels with the Maidan, which, according to the Kremlin, was sponsored by Western intelligence services and carried out by “Ukrainian Nazis.”

The Kremlin has also launched the narrative of “protecting the Russian-speaking population” in Kazakhstan in full force. “But almost 3.5 million Russians live in Kazakhstan. And their fate cannot but worry Moscow, because how can one know who will rise to power in troubled times,”- writes Komsomolskaya Pravda.

Oleksandr Zamkovoi