By Viktor Denisenko, in cooperation with Vilnius Institute for Policy Analysis, for StopFake

On February 23, 2018, the Radio and Television Commission of Lithuania blocked the transmission of RTR Planeta – a Russian-state television channel – for 12 months. RTR Planeta was already temporarily banned in Lithuania twice before for one- and three- month periods respectively. Similarly, other Russian-state channels have also faced similar fate before.

Even today, 27 years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russian television channels are still operating in Lithuania. They have a stable audience, mainly comprising local Russian-speaking and Polish-speaking minorities. Russian TV channels attract the audience by quality entertainment and cultural production. The latter practice could be seen as acceptable if these channels stopped “selling” their viewers not only entertainment or culture but also propaganda.

In Europe and the United States, almost everyone knows that information channels such as RT or Sputnik are just another tool of the Kremlin aggressive and revisionist foreign policy. But these channels do not challenge the Lithuanian information space – they are simply not that popular there. The real danger for Lithuania are the Russian state TV channels adapted specifically for the Baltic market. In this case, adaptation largely means replacing Russian advertisement with local commercials. Aside from that, the programs of these channels repeat the programs of their original Russian counterparts.

It is also no secret that the national state TV channels in Russia are directly or indirectly controlled by the Kremlin. The latter is the leading provider of state-sanctioned narratives, including all kinds of propaganda stories Moscow uses for internal and external political purposes. Famous TV presenters such as Dmitry Kiselyov or Vladimir Solovyov cannot be called journalists in any meaningful sense – they are mouthpieces of state propaganda. For example, Vladimir Solovyov’s show regularly spreads disinformation and misleading narratives about the Baltic States and the West. Such TV talk-shows in general (not only Solovyov’s program) are widely seen as “a part of a general trend of media mobbing in Russia, which mirrors the treatment of opposition voices in the country”.

For his part, Dmitry Kiselev is described in the EU sanctions list as a “central figure of the government propaganda supporting the deployment of Russian forces in Ukraine”. Kiselyov in his program regularly spreads outrageous lies about events in Ukraine, often spinning false narratives about “fascist coup” in Kyiv, and claimed that Russia is the only country in the world which could turn United States into “radioactive ash”. In short, Russian-state TV channels have become the primary source of anti-EU, anti-NATO and anti-American fake news. We may also remember the much-commented false story about the alleged “crucifixion of a little boy in Slovyansk”, which was spread by Pervyj Kanal in 2014 with the aim to discredit the Ukrainian army.

Through adapted TV channels the above-mentioned and similar malign anti-Western narratives are directly transmitted to Lithuanian information space. People who watch only these channels are receiving the Kremlin-constructed image of world. This image is sustained by a constant flow of lies and fake news. Russian TV watchers are becoming, as articulated by Peter Pomerantsev, inhabitants of Kremlin’s hall of mirrors.

Ban of retransmission

Temporary bans on the transmission of several Russian state TV channels were pursued by the Radio and Television Commission of Lithuania (a similar practice was implemented in Latvia too). Such a decision is made if the content of a channel breaks the Lithuanian law. In fact, this issue is directly related to the issue of propaganda. The Constitution of the Republic of Lithuania notes that the freedom to express opinions and to spread information is incompatible with criminal actions such as “incitement of national, racial, religious, or social hatred, incitement of violence or discrimination, as well as defamation and disinformation”. Russian state TV channels sometimes violate these rules. Decisions to temporarily stop the broadcasting are made after an investigation. Such a decision can only be made by the court following an appeal of the Commission.

A temporary ban was first issued in Lithuania in 2013. It ensued after Pervyj Baltijskij Kanal (PBK) broadcast a television show “Man and the law” which repeated the Soviet authorities’ lie that during the tragic events of January 13, 1991 in Vilnius, the responsibility for 14 civilian fatalities fell not on the Soviet army but on the “unknown Sajūdis’ (Lithuanian national independence movement) snipers”. In fact, during the night of January 13, 1991 Soviet regular troops and special forces stormed the building of Radio and Television Committee and the TV tower. As a result of the action, 14 civilians were killed, hundreds injured.

According to the court’s decision, for three months the PBK channel could not broadcast on Lithuanian territory any media production that was not made in the EU and/or not in the European Convention on Transfrontier Television signatory countries. Russian Federation has not yet signed the Convention. But PBK found a way to circumvent the decision. During the three-month ban, the channel broadcast movies and TV series made by Russian producers in Ukraine – a country which had signed the Convention.

Subsequent court decisions were more resolute, aimed at stopping the broadcasting entirely for a certain period of time. It became a usual practice since Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the subsequent intensification of the Kremlin propaganda activities. In 2014, RTR Planeta and NTV Mir Lietuva were banned for three months. RTR Planeta was also repeatedly suspended for three-month periods in 2015 and 2016. In 2017, another channel TVCI was blocked twice, first time for one month, second time for six months. Finally, in 2018, RTR Planeta broadcasting was blocked again, this time for one year.

In February 2017, Lithuania received support from the European Commission. In a statement, the Commission noted that the decision to suspend the channel RTR Planeta due to incitement of hatred was compatible with the EU law. The European Commission provided similar support in 2018 as well.

No frontiers for television

The idea of television without frontiers is not new: it correlates with the fundamental single-market principle of European Union. The European Convention on Transfrontier Television was adopted in 1989. It also become a ground for Directive “Television without Frontiers” of the European Economic Community (European Union) adopted the same year. In the regulation of the European Union, this Directive was replaced in 2007 by the new Audio-Visual Media Services Directive, which was changed once more in 2010. The Directive, as well as Convention, is meant to protect the free flow of information.

Notably, the Convention was intended for all member states of the Council of Europe. For example, the Ukrainian parliament ratified the Convention in 2008. It was “the first international treaty creating a legal framework for the free circulation of transfrontier television programmes in Europe”.

The main idea of both Directive and Convention was a free circulation of information. The preamble of Convention affirmed “the importance of broadcasting for the development of culture and the free formation of opinions in conditions safeguarding pluralism and equality of opportunity among all democratic groups and political parties.”

The idea of free exchange of information is one of the cornerstones of liberal democracy, but it may become a weakness in the face of malign propaganda and disinformation interference. The success of Moscow’s hostile actions is a case in point. On the one hand, the Russian Federation has not ratified the Convention, which allows Moscow to keep its information sphere closed to other broadcasters. On the other hand, Kremlin uses these legal loopholes to pursue its nefarious activities in Europe’s information sphere.

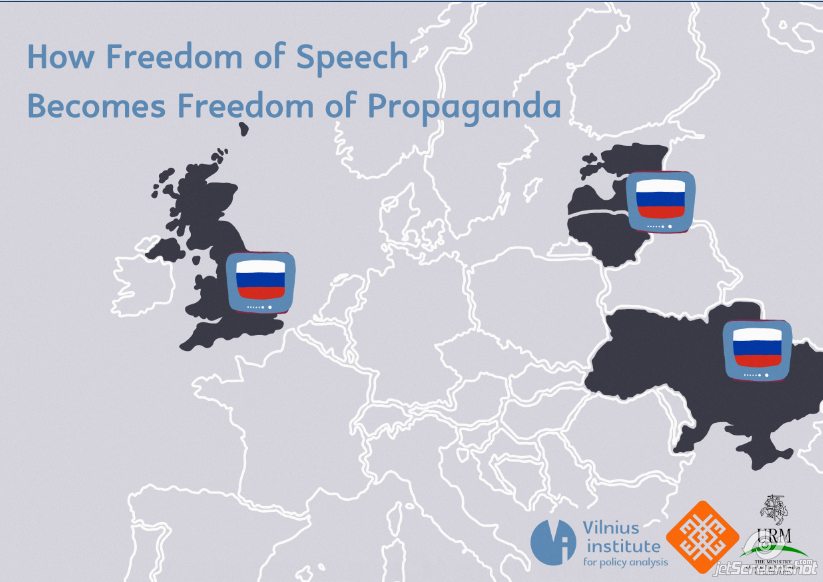

As mentioned before, many Russian state TV channels operate in Lithuania. The problem is that formally these are not “Russian channels”. For example, the infamous RTR Planeta is registered in Sweden. Similarly, PBK is a “Latvian channel”. In this way such channels become resident players in the European single market.

Importantly, the transmission of PBK in the Baltic States is in the hands of the Latvian-registered Baltijas Mediju Alianse Ltd. Another company bears a very similar name – yet in this case, it is registered in the UK: Baltic Media Alliance Ltd (BMA Ltd). This company provided UK Ofcom licenses to several Russian channels (e.g. NTV Mir Baltic, NTV Mir Lietuva, REN TV Estonia, REN TV Lietuva etc.). The Latvian BMA used these licenses for broadcasting in the Baltic States. All the aforementioned channels could be found on the list of Ofcom-licensed channels in the category of “Cable and Satellite Channels”.

In other words, the Kremlin-backed propaganda in Lithuania (and the other Baltic States) is currently spread via European channels. As a result, we have a very complicated situation. Being a member of the European Union, Lithuania cannot close its information sphere to European channels without breaking the international law. Hence a temporary ban of transmission is the most Lithuania is legally allowed to do in these circumstances.

Another interesting fact: Baltic Media Alliance Ltd is a registered lobbyist in the EU. In the register, the company is described as “Broadcaster of non-EU-language and EU-language TV channels on the territories of Latvia and Lithuania representing second largest TV media holding in the Baltics”. Data shows that from 2014 BMA Ltd spent more than 15 000 euros every year on lobbying activities. In other words, BMA not only takes care of providing UK licenses for Russian state televisions but also seeks opportunities to influence European policymaking and legislation processes.

Conclusions

TV channels specialising in pro-Kremlin propaganda feel comfortable in the European Union. Moscow knows how to use various loopholes and opportunities provided by the free market and liberal democracy (for instance, the principles of freedom of speech and access to information) for its own anti-democratic purposes. In short, the Kremlin is playing “on the European field” and winning the game with the West’s own tools.

Lithuania and Latvia are trying to draw attention to this problem. Some experts and politicians have proposed to revise the Audiovisual Media Services Directive. It was agreed that this document should be updated to include “stronger rules against hate speech and public provocation to commit terrorist offences”. It is one of the ways the West could respond to the challenge of (not only Russian) propaganda. On the other hand, this measure alone will not be sufficient.

Of course, every country could try to find an individual solution. For example, Latvians are pondering the idea that in the basic package of TV channels offered to cable network users, no less than 90% of content should be produced using the official languages of EU. The proponents of this decision hope that it will “reduce the level of Kremlin propaganda in Latvia”.

In any case, the crucial question in these circumstances is how to stop the Kremlin propaganda without compromising the fundamental principles of Western liberal democracy. Finding an answer to this question should be the primary task not only for Lithuania and other Baltic States but also for the West as a whole. In order to meet this urgent challenge, the West needs to find effective ways to control pro-Kremlin propaganda and disinformation flows in the European information sphere while preserving the democratic values it espouses.

By Viktor Denisenko, in cooperation with Vilnius Institute for Policy Analysis, for StopFake

Viktor Denisenko is a lecturer of Faculty of Communication of Vilnius University. The article was produced in cooperation with Vilnius Institute for Policy Analysis, a Lithuanian think tank.

—

This article is part of the project aimed at strengthening democracy and civil society as well as fostering closer ties with the EU Eastern Partnership countries (Ukraine, Moldova, Georgia) by spreading independent information with the help of contemporary solutions. The project is implemented by Vilnius Institute for Policy Analysis. It is financed as part of Lithuanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ Development Cooperation and Democracy Promotion Programme.