By Oksana Poluliakh

Today, almost everyone has access to AI tools that can create images that appear realistic-at least at first glance. However, these technologies have become powerful tools for those seeking to manipulate public opinion. Russia is actively using AI in its information warfare. How exactly do AI-generated fakes work, why are they particularly dangerous in wartime, and how can we identify them? This text delves into these questions.

Can We Recognize AI-Generated Images?

According to a study by the University of Chicago, only 60% of Internet users can tell whether an image was created by AI. This is a cause for concern, especially as these technologies continue to improve. Ukrainians are no exception. A survey conducted by Kantar Ukraine in February 2024 revealed that while 79% of respondents know what AI is, only 42% feel confident in their ability to recognize such content.

The inability to distinguish between real and generated content has significant implications, from copyright infringement to the risk of disinformation and fraud.

Why Is AI-Generated Content Dangerous?

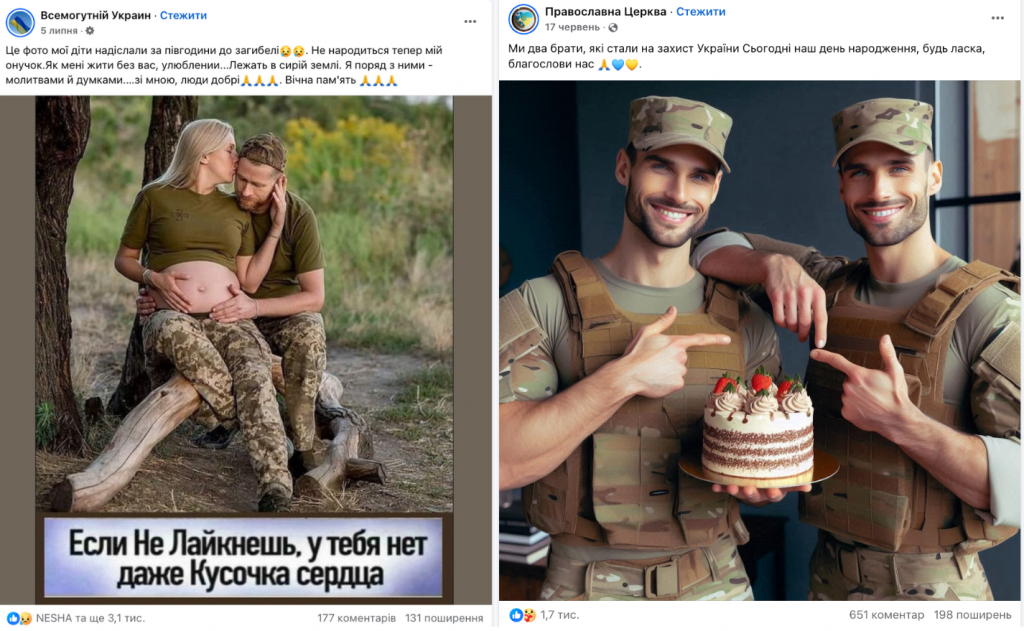

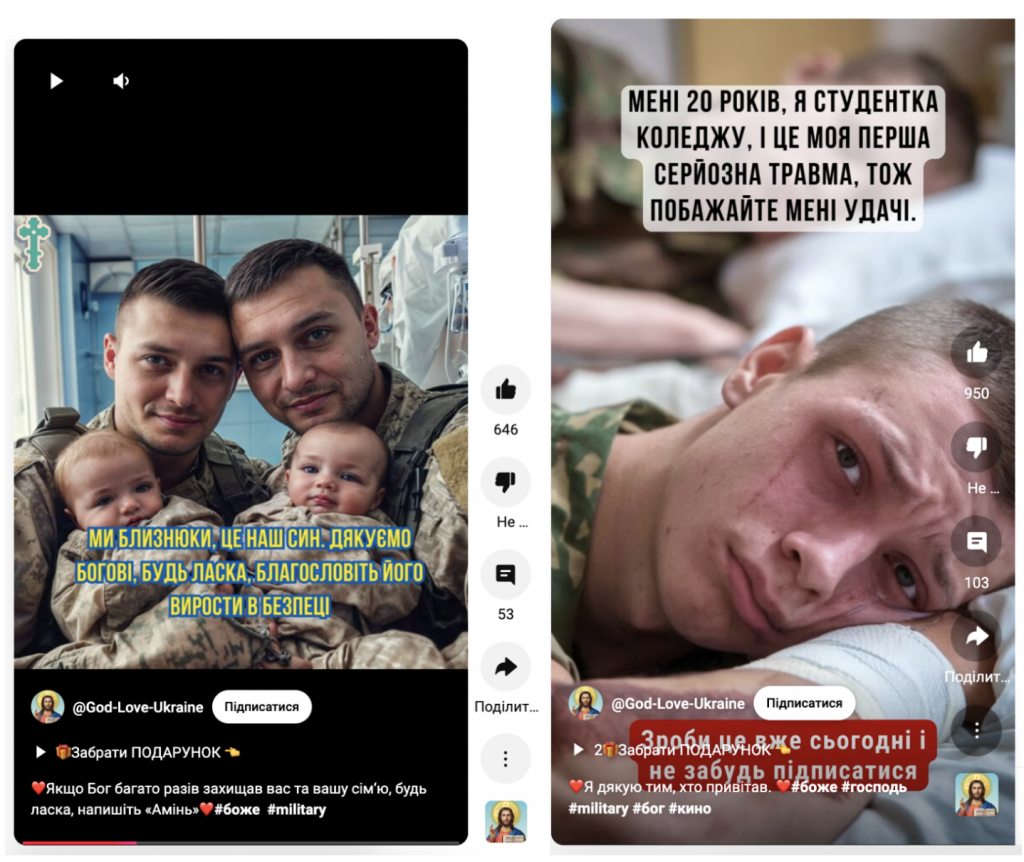

AI-generated images are often used to manipulate emotions. You’ve probably seen images in your Facebook feed that appear to be soldiers asking for support during important moments – a birthday or a wedding. What’s wrong with liking a post about a soldier who just got married? Or maybe commenting to cheer up a young man who apparently didn’t get a birthday greeting from his family?

Such posts garner thousands of likes and comments, increasing the reach of Pages. However, their emotional appeal can mask malicious intent: Pages often change their topics or are used to spread propaganda.

Ukrainian social media platforms are not the only ones dealing with the spread of AI-generated content. American Facebook has also been flooded with similar images: elderly people, people with amputated limbs, and infants. These posts are often accompanied by emotional captions such as “No one has ever blessed me” or “Made this by hand. I’d love your feedback.” In August 2024, Renée DiResta of Stanford University and Josh Goldstein of Georgetown University’s Center for Security and Emerging Technologies published research showing that AI-generated images are actively exploited by scammers and spammers. These images help sites quickly grow their audience, increase user engagement, and ultimately monetize their popularity. As a result, these pages often change their names and begin posting entirely different content, sometimes fraudulent in nature.

In addition to changing page names, scammers also manipulate the content of posts. For example, yesterday you may have shared a picture of a soldier asking for prayers for victory, only to find today that the same post has been replaced with completely different, even contradictory, content. This tactic misleads users by creating the illusion of widespread support for new posts when the likes and shares were originally garnered for something else. StopFake has investigated such cases: for example, scammers have edited a post to turn it into a fake, as described in the article Fake: Ukrainian Pilot Stole Plane and Fled to Africa to Be with Lover.

Analysts at the Institute of Mass Information (IMI) have discovered that a religious organization founded in China is using AI-generated images to recruit Ukrainians into its ranks. Under emotional photos of Ukrainian soldiers or elderly people, users like posts inviting them to join private WhatsApp groups for group prayers. However, instead of the promised prayers for Ukrainian soldiers, these online gatherings spread narratives that glorify Russia, the aggressor state. IMI experts stress that these methods target vulnerable people, especially those with family members serving in the military. These individuals are often concerned about the course of the war and seek emotional support.

In times of war, such actions seem particularly threatening. The Center for Countering Disinformation under the National Security and Defense Council (NSDC) notes that pages with AI-generated images attract large audiences that are insufficiently critical of online information and susceptible to information manipulation. This provides a platform for adversaries to promote narratives harmful to Ukraine.

In October 2024, Microsoft released a report on cyber threats for the period from July 2023 to June 2024. According to the report, countries such as Russia, Iran, and China are increasingly using AI to increase the reach, effectiveness, and engagement of their information campaigns. Even AI tool developers admit that their products, such as ChatGPT, are being used unchecked by Russia to manipulate public opinion worldwide.

One of the most notable examples of Russia’s information attacks against Ukraine was the wave of AI-generated images of Ukrainian soldiers that circulated in late 2023. These images were accompanied by texts claiming that Ukrainian soldiers in Avdiivka, Donetsk region, were praying for salvation and asking Ukrainians to pray for them. Given the intensity of the fighting in the area, such messages had a profound emotional impact.

However, according to StopFake’s observations, the primary distributors of these posts were bot-like accounts. The scale and speed of the spread of the content suggests that this campaign was a carefully planned part of Russia’s disinformation operations. Its primary goal was to instill fear, panic, and despair among Ukrainians while undermining the morale of the defenders.

This campaign also demonstrates how effectively AI technologies can be used to create the illusion of widespread support or panic. Some images of soldiers in moments of despair appeared so realistic that they could confuse even experienced Internet users. In addition to undermining morale, such manipulations aim to exacerbate internal divisions within society, sow doubts about Ukraine’s defense strategy, and construct an image of a “tired” army.

This photo shows a child who supposedly survived another Russian attack on Dnipro. The caption emotionally underscores the tragedy: “He will always remember who destroyed his world.” The boy stands against the backdrop of a destroyed building, holding what appears to be a piece of bread. A flag patch on his jacket clearly identifies him as Ukrainian. Despite the obvious signs that the image is not genuine, many users expressed sincere sympathy for the child in the comments, inquiring about the fate of his parents.

This image went viral on January 14, 2023, shortly after the missile attack on an apartment building in Dnipro that claimed the lives of 46 people, including six children, and injured around 80. Even the official accounts of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine shared this content, sparking a wave of outrage and criticism, as the use of AI-generated images in such a context undermines trust in actual events.

Similar AI-generated images mimicking the destruction in Ukraine and the suffering of civilians often go viral. They are sometimes shared more widely than authentic photographs of the aftermath of Russian attacks. Some justify this by claiming that such images are merely “illustrative,” but statistics show otherwise: 40% of users cannot distinguish AI-generated images.

The use of such photos not only blurs reality, but also distorts the truth about Russia’s war crimes. Russian propaganda uses the saturation of the information space with such material to promote the narrative that civilian casualties in Ukraine are fabrications by Ukrainian or Western intelligence. The logic of this propaganda is simple: “If the Ukrainians are lying about the Dnipro boy, they could be lying about other tragedies.”

For more on how Russian disinformation creates and spreads such doubt, see the StopFake materials: Fake: Mass Civilian Casualties in Kyiv Region Staged, Fake: Atrocities of Russian Soldiers in Hostomel Are Staged and Videofake: Report on Civilian Casualties in Ukraine Staged.

These cases highlight the need for critical thinking and information verification, as the careless dissemination of AI-generated content inadvertently supports Russian propaganda.

How to Detect AI-Generated Images?

Identifying fake images created by artificial intelligence (AI) can be challenging, but it is possible. Here are the key approaches and criteria to help determine whether an image is real or AI-generated.

1. Checking Watermarks and Metadata

- Watermarks: Check if the image contains a watermark from an AI generator (e.g. MidJourney or DALL-E). These watermarks are often located in the corners of the image.

- Image Description: Check the captions or comments that accompany the image. The author may give credit to the original source or indicate that the image was generated by AI.

- Metadata: If available, metadata analysis can provide information about the date of creation, location, camera settings, and even the tool used to create the image. Metadata analysis can be an important tool for authenticating images. To do this, you can use programs such as ExifTool or Exif Pilot that need to be installed on your computer. These programs provide a detailed analysis of file metadata and are suitable for working with different formats. A handy online tool is metadata2go, a service that allows you to quickly check metadata by uploading a file to a website.

2. Visual Analysis of the Image

AI-generated images often show distortion or unnatural details. Common indicators include

- Background: The background may appear blurred or distorted. Objects in the background may be oddly shaped, misaligned, or assembled inconsistently.

- Lighting: Look for anomalies in the distribution of light, such as false shadows, inconsistent brightness, or lighting that defies physics (e.g., sunlight that does not realistically illuminate an object).

- Facial and Limb Details:

- Facial asymmetry (e.g., uneven eyes or misaligned ears).

- Extra fingers, unnatural limb positions, or irregularities in nails.

- Small Details and Text: Uniforms, camouflage, or patches may contain errors such as fictitious designs or illogical placement. Text on images often consists of random characters, gaps, or nonsensical patterns.

- Duplication and Repetition: AI often creates people with nearly identical faces or replicates textures. Walls, furniture, or other objects may repeat unnaturally.

- Spatial Relationships: Examine how elements are positioned. Items such as eyeglasses or jewelry may be “blended” into the face or placed unnaturally away from it.

- Digital Artifacts: Look for pixelation, unusual color anomalies, or blurring in illogical areas.

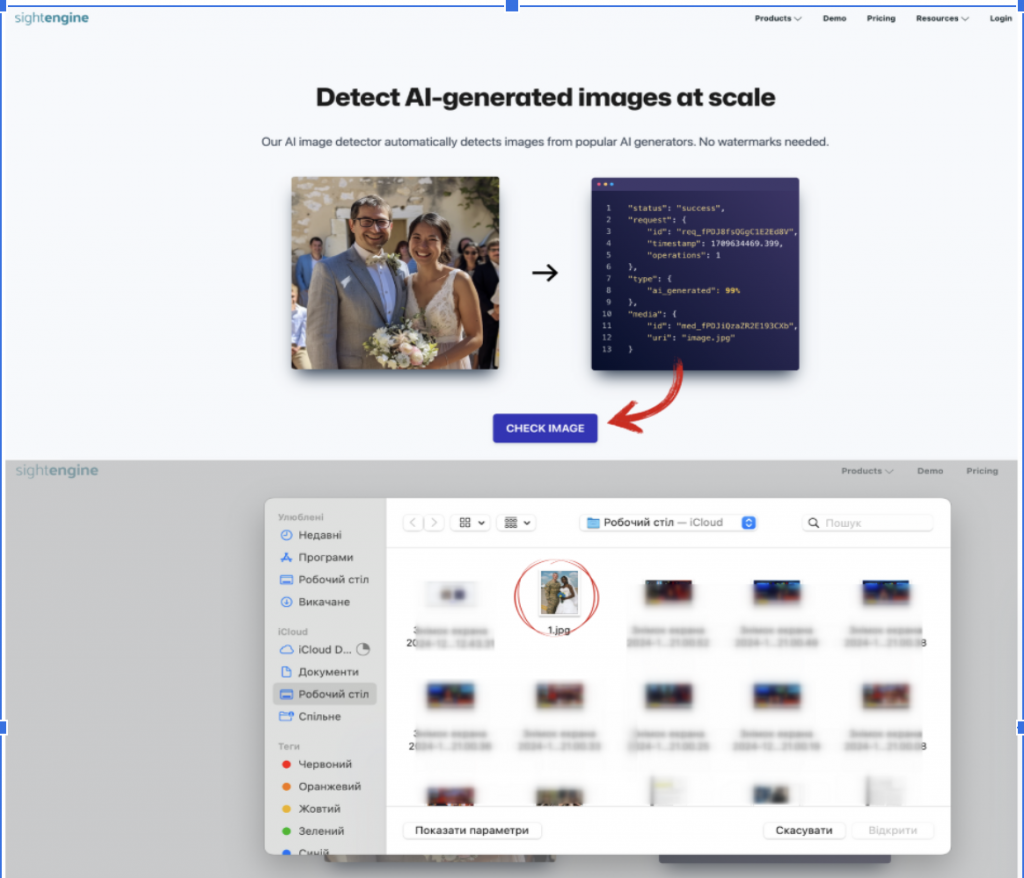

3. Using Specialized Tools

Various AI detection tools can analyze images and determine if they were created by artificial intelligence. Here are a few popular options:

This tool specializes in analyzing images and videos for possible manipulation or AI generation. You can upload images directly to the site without registration and get quick results, making it a user-friendly option for simple checks.

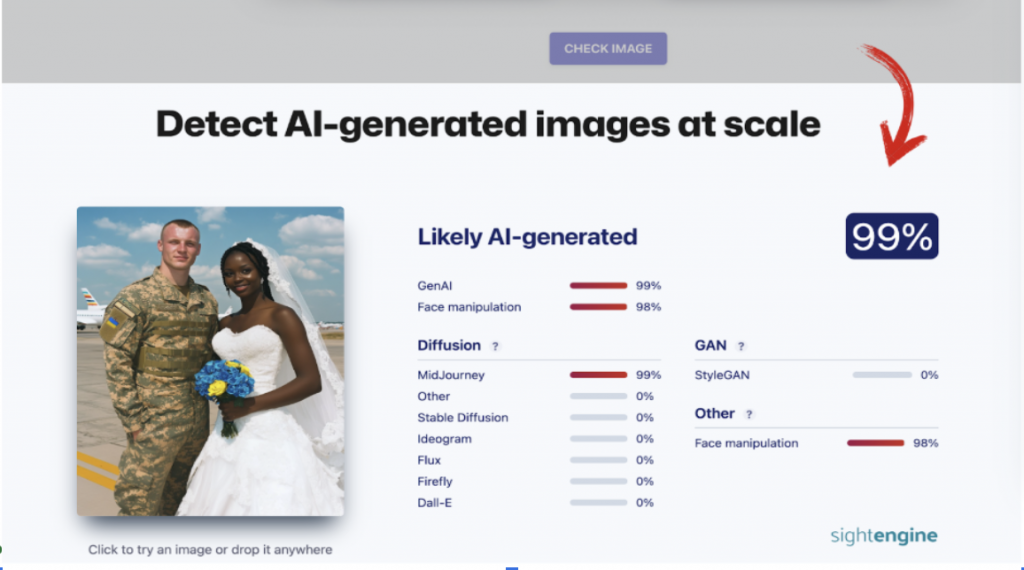

SightEngine is a powerful tool that offers a wide range of capabilities, including identifying AI-generated images, checking content for compliance with standards, and detecting manipulation.

The service is available in a free mode with limited features. You can check images for free and without registration: just go to the “Detect AI-generated images at scale” section, upload the image to the website, and wait for the results. SightEngine is able to determine the probability that the image was created by AI and indicate a specific generator (for example, MidJourney, DALL-E, or Stable Diffusion).

This tool works as an online service and allows you to quickly determine whether an image has been created by artificial intelligence. For a basic analysis you can use the free trial version, but you need to register on the website. After registration, you can upload an image and the system will provide the results of the check, indicating the probability of AI generation. The free version allows you to check up to 10 images.

The tool is ideal for quick image verification, but it cannot be used without registration.

Hive Moderation is an API-based tool for automatically moderating large volumes of images. At the same time, the service offers a free demo version for individual users. To use it, you need to register on the website.

However, you can check images without registering. To do so, go to the AI-generated content detection section and select the “See our AI-generated content detection tools in action” feature. You will be able to upload images and receive basic review results, including information about the potential use of AI generators.

Each of these tools can help you with anything from quick analysis of individual images to large-scale content verification.

Important: These tools do not always provide accurate results, especially if the image is of poor quality. They should be used as supplemental methods rather than primary methods. We also recommend combining these tools with other verification methods for maximum accuracy.

4. Interactive Learning

To improve your ability to identify AI-generated images, you can use interactive platforms such as the New York Times quiz. These platforms help train your attention to detail and improve your ability to spot fakes.

Artificial intelligence offers great potential, but it also poses risks to the information space, especially in times of war.

AI-generated images can evoke strong emotions, mislead audiences, and serve as tools in adversaries’ disinformation campaigns.

It’s important to remember that any interaction with suspicious content-liking, commenting, or sharing-can benefit the adversary by advancing propaganda narratives, undermining trust in real facts, and potentially fueling societal panic. Interacting with information in wartime requires responsibility. Fact-checking and consciously engaging with content not only helps protect yourself, but also contributes to societal resilience against information threats.

This article was produced with support from NDI