Russian state media have a credibility problem, and they know it.

According to a 2019 survey by the independent pollster, Levada Center, about 50 per cent of Russians think that information from state-controlled TV channels – the main source of news for most Russians – is unreliable. And the number is growing each year, along with increased faith in independent web outlets and social media as alternative and more reliable sources. This is a problem for the pro-Kremlin disinformation outlets, but one for which it has found a crafty solution.

From seed to harvest

The prestigious foreign media outlets don’t make a habit of seizing on and supporting pro-Kremlin disinformation narratives. Hence, disinformation outlets simply state that foreign media do indeed support their views.

This way you will find the executive editor of The Economist asserting that the UN pursues dubious policies; The Guardian reporting that 80 per cent of humanity could die of Covid-19 in the next decade; Die Welt calling the White Helmets “pseudo human rights defenders”, and accusing them of embezzlement; Foreign Policy proposing different scenarios to overthrow Lukashenka; Newsweek confirming the existence of a US coup in Iran; Die Welt (again!) explaining the EU organised protests all over Eastern and Southern Europe; and a leading Polish security expert telling his country that it should be afraid of Russia’s missiles (all are real disinformation cases debunked by EUvsDisinfo).

The manipulations modus operandi

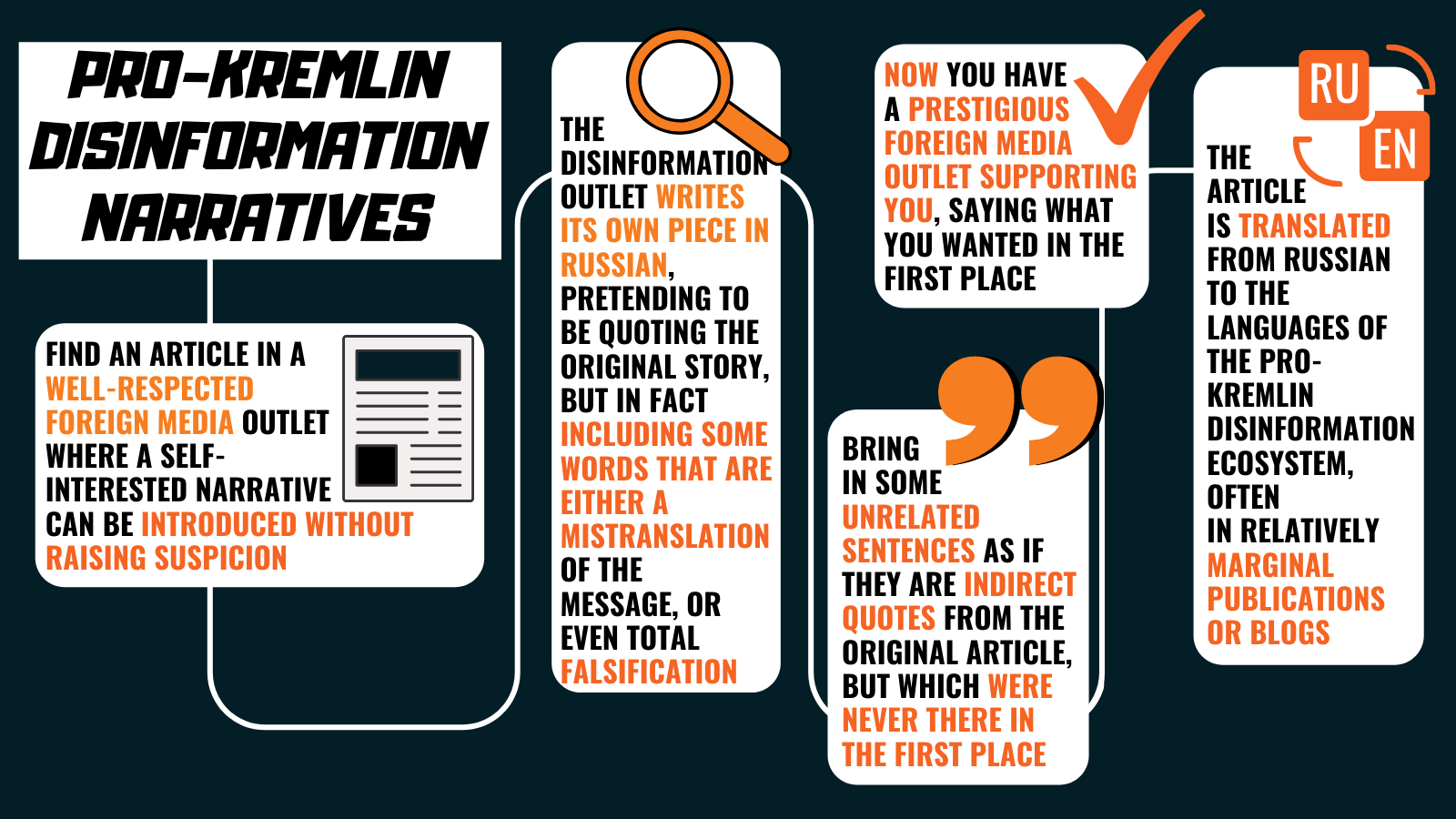

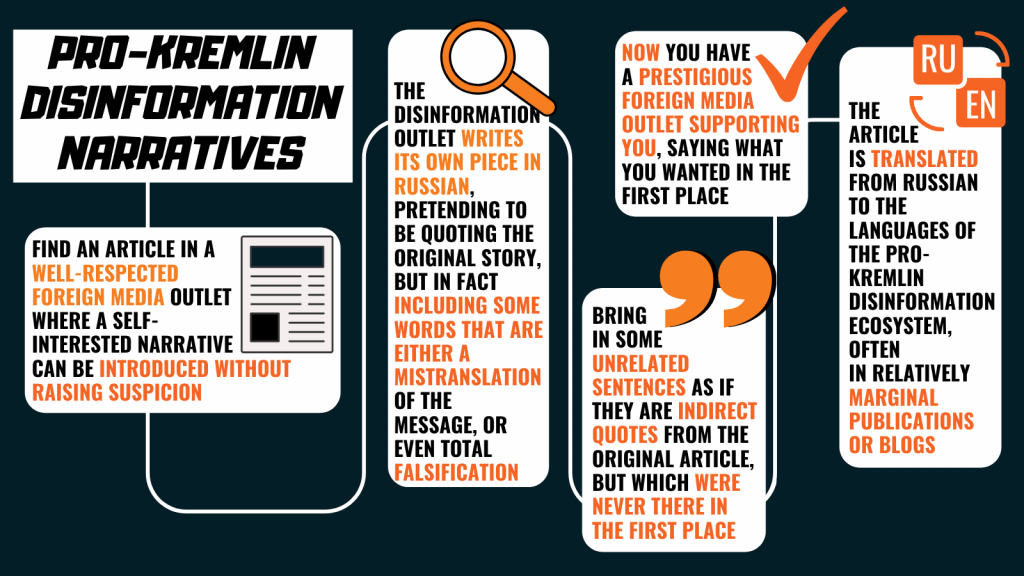

How is it that such distinguished magazines and newspapers end up promoting pro-Kremlin lines? Well, there are several steps to this wily choreography. First, pro-Kremlin disinformation outlets find an article in a well-respected foreign media outlet where the borrowed narrative can be introduced without raising suspicion.

Second, the disinformation outlet writes its own piece in Russian, pretending to be quoting the original story, but in fact including facts and stories that are either a gross mistranslation of the message, or even a total falsification.

Another frequent technique is to bring in some unrelated sentences as if they are indirect quotes from the original article, but which were never there in the first place. Ta-daaaah! Hey presto! Now you have a created an appearance that prestigious foreign media outlets supporting your story.

Next, the article is translated from Russian to the languages of the pro-Kremlin disinformation ecosystem, often in relatively marginal publications or blogs such as News Front. A new headline is chosen for the article (oh, what a coincidence!) and it is the same message that you want to highlight.

This “text” engineering gets you The Telegraph backing claims that people are being deliberately infected via contaminated Covid-19 tests (in Czech); an op-ed written by three former US ambassadors to Ukraine calling for a Russian withdrawal from Crimea and published in NPR turned into a story of three active US diplomats threatening Russia (in Hungarian); and a third-hand quote of a Russian military officer in an article in The National Interest morphing into a publication confirming that Russia’s Avangard missile could destroy any US defences (in Spanish).

Diagnosis is difficult

Unfortunately, this modus operandi is hard to detect. Diagnosis requires both awareness and will to fact-check, including sufficient command of several languages to spot the forgery (English, Russian and a third in which the story was re-translated). Identifying these fabricated stories takes time and energy, too, which is why pro-Kremlin disinformation outlets use them so much.

Any regular culprits?

InoSMI, an internet media project (owned by Rossiya Segodnya, the matrix company of RT) and which translates articles from foreign media into Russian, is rather adept at this distorting. According to researchers at Ghent University, during the Crimean crisis in 2014, InoSMI regularly twisted articles from The Guardian, The Wall Street Journal, Le Monde and Le Figaro through “selective appropriation, shifts in translations and visual strategies” to produce “a discourse more in line with the Kremlin’s official viewpoints than the original data set”.

As researchers noted, “in the translation process, Russia emerges as a powerful yet honourable player on the global stage, while the West’s morally ambiguous position in the conflict and the divisions within its ranks are brought to the fore”. InoSMI has since continued its translating and manipulating crusade, pushing out low-quality articles about Ukraine in French or Swedish, which are in turn reproduced by other Russian media, only to be retranslated again and reframed in News Front or Sputnik.

On the subtlety scale, this technique is certainly more low-key than inventing non-existent British MPs that support your version of events in Crimea or forging Bellingcat chats. Seriously, why bother with the hard work of public diplomacy and media relations? Why go to the trouble of explaining your version of events to foreign journalists in the hope that they will reproduce it? Just fake it. Only the sky’s the limit.