By Gustav Gressel, for European Council of Foreign Relations

SUMMARY

There is a large amount of ideological overlap between some European political parties and the Russian government. Significantly, these include parties considered to be ‘mainstream’ – it is not just ‘fringe’ parties that share elements of the Kremlin’s world-view.

European political parties range from those that are ‘hardcore’ in their ‘anti-Westernism’ to those that are fully pro-Western. The former are much more open to cooperation with Russia and are generally aligned with its priorities.

Strong election showings from anti-Western parties can change the character of entire national political systems. Most countries are ‘resilient’ to ‘anti-Western’ politics, but a large minority are favourable towards Russian standpoints. Important players like France and Italy form part of the ‘Malleable Middle’ group of countries which Moscow may seek to cultivate.

The populist, anti-Western revolt of the last decade did not originate in Russia. But it is yet to run its course, and Western politicians should act now to prevent Russia taking further advantage of it.

Download: PDF

POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

To make progress in this area, the problem must first be named. Anti-Western elements, exploitable by the Kremlin, exist not only on the fringes of European politics, but reach right into the heart of established parties.

Strengthening counter-intelligence services, tightening anti-corruption legislation and supervision, strengthening anti-trust laws, and strictly implementing the third energy package would make it more difficult for Russia to develop and exploit its various channels of influence.

It is up to politicians of pro-Western parties, especially ‘mainstream’ ones, to spot such trends, show leadership, and halt the drift towards a place where liberal democracy transforms itself into something rather less open.

INTRODUCTION

Russia is increasingly getting to know some of Europe’s political parties. And it is not just that Russia is coming to Europe – some European political parties are coming to them. In October 2016, members of the Italian political party Lega Nord travelled to Crimea, making up the largest component of the visiting Italian delegation. One of the party’s leading members, Claudio D’Amico, had acted as an ‘international observer’ at the peninsula’s status referendum two years previously.[1]

Earlier that same year, in February 2016, Horst Seehofer, head of Germany’s Christian Social Union (CSU), Angela Merkel’s key coalition partner, made an official visit to Moscow. Although insignificant from a German perspective, the Russian media celebrated Seehofer as the alternative to Merkel and as the German leader who would re-establish German-Russian friendship.[2] At that time, Seehofer had just recently threatened legal action over the German chancellor’s policy towards refugees, a message also frequently heard in Russian propaganda.[3]

These types of contacts and ideological convergences show the growing strength of relationships between the Russian authorities and European political parties. Over the last few years, ‘Russian meddling’ in general elections in the West has become a constant media focus. But, without an election, the story soon drifts away. This is a mistake. The world’s attention should linger a bit longer on the landscape that the Russians themselves see when contemplating their neighbours. For Europeans in particular it is time to understand which countries may appear to the Russians as fertile ground for growing fellow ideological travellers.

Russia is preoccupied with building a neighbourhood that responds to its interests and treats it as a great power. For years, the Kremlin has tried to find forces that would support or tacitly agree to this world-view. Where is there significant overlap of interests and ideologies between it and players in Europe? Which European political parties and leading politicians are open to pursuing goals it shares? Are these forces significant, or are Russian fellow travellers restricted to the noisy but less important anti-system opposition?

With those questions in mind, this study examines the European political landscape that the Russians see. The research underpinning it looked at all 252 parties represented in the 28 national parliaments and the European Parliament and attempted to determine how ideologically aligned with Russia each of them is.

One crucial finding of this study is that it is not only the ‘fringe’ or so-called ‘populist’ parties that align ideologically with Russia. In fact, the research reveals that important common ground exists between the Russian government and many mainstream political parties, often based on a narrative of ‘anti-Westernism’ that originates within Europe itself.

The second part of the study examines how the presence of these parties is affecting the larger political system. It reveals how some countries’ political systems are becoming more aligned with Russia over time as new parties sharing the same priorities as Russia win increasing representation in national parliaments.

Anti-Westernism and ideological affinity

Contacts between European and Russian political players are nothing new, despite their often fractious relationships; nor are the meetings of minds which have frequently recurred over many decades between Europeans and Russians. Whenever an old political, social, or economic order has come to an end, discussions about the ideal nature of a new one start to emerge. In both Russia and Europe such shocks took place several times in the twentieth century: the end of the monarchic order in Europe 1917-1918, the end of the fascist or national socialist order in 1945, and the end of the Communist order in 1989. In all of these historic moments, Russian and European thinkers influenced each other, although Europe and Russia ultimately developed in different ways.

As far back as 1995, Richard Herzinger and Hannes Stein described the rising ideological discontent with the ‘Western model’ of the post-1945 European order (founded on free trade, an open society, and a transatlantic link based on common liberal values). Borrowing from the concurrent debate inside Russia between Westernisers and Slavophiles, they described those within Europe opposing the post-1945 order as “Antiwestler” (anti-Westerners).[4] They identified a “cross-over” in which anti-Westernism inspired both far-left and far-right political thought within Europe. The transatlantic and liberal ideological foundations of the Western order were particular targets of the Antiwestler.

While it is predominantly about German authors, thinkers, and political activists, Herzinger’s and Stein’s book is important for two reasons. First, it provides a compelling and systematic account of the anti-Western ideology that underpins populist parties’ opposition to the established order. Second, the actors and ideologues described as Antiwestler back in 1995 are today among the key so-called Putinversteher, members of the German elite who express empathy for Russia and its president, Vladimir Putin.[5] In the mid-1990s, Russia had no money or inclination to fund propaganda campaigns in the West, but the ideological patterns of what would later develop into affinities with the Russian regime were already visible. Today, anti-Westernism has become the core ideological connection between Russia and a wide variety of political parties in Europe, including some mainstream parties. It is now time to examine the current situation and to consider the European political landscape as Moscow may view it.

Methodology

This study examined all 252 parties represented in the 28 national parliaments and the European Parliament. Researchers and leading journalists in all EU member states completed a survey containing 12 multiple-choice questions covering party views on:

• support for the European Union;

• liberalism as a European value;

• secularism as a European value;

• support for the NATO/EU-centric

European security order;

• the country’s support for transatlantic relations;

• free trade and globalisation;

• the country’s relations with Russia;

• the country’s sanctions on Russia;

• the country’s support for Ukraine;

• refugees and migration;

• the war in Syria;

• the particular party’s links to Russia.

The survey provided sufficient data to assess 181 parties represented in national parliaments and/or the European Parliament and the 22 countries where they are elected. Each party received a score for individual questions and an overall score. Using these results, the sum of all answers about a single party provided an index number, according to which a party was ranked on a scale from pro-Western to anti-Western. According to the score received, the party is described as either ‘pro-Western’ or ‘anti-Western’. If the party received negative scores on the questions related to Russia, it is described as ‘pro-Russian’. A more detailed description of the methodology, the quantitative aspects of the findings, and explanations of conclusions drawn are provided in an annex to this paper.

To see the full ranking of political parties referred to in this paper, please see Table 1 in the annex.

European political parties and anti-Westernism

The paper divides the 181 political parties into four groups according to their ranking on the anti-Westernism scale. Thirty parties are “Hardcore anti-Western parties”, meaning that they qualify as anti-Western on most or all questions. A further 31 parties qualify as “Moderately anti-Western” because they accept some parts of the Western model. Forty-nine parties are considered “Moderately pro-Western”, meaning that they accept more parts of the Western model than they reject. Finally, the largest number: 71 parties are essentially pro-Western. This is explained in greater detail below.

Hardcore anti-Western parties (30 parties)

The political parties with the most anti-Western patterns are far-right, ‘anti-system’, or even fascist parties: the Ataka party in Bulgaria, Kotleba – Our Slovakia, Jobbik in Hungary, the Front National in France, Fratelli d’Italia-Centrodestra Nazionale and Lega Nord in Italy, the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP), and the Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ). The ‘top 30’ parties (headed by Ataka, with the Greek Communist Party in 30th place) were categorised as anti-Western on all but a few questions. These parties are against the EU, reject free trade and globalisation, oppose political and social liberalism, and perceive migration from non-Christian communities as an existential threat. Right-wing parties are predominant in this category, although some radical left-wing parties, such as the Bulgarian Socialist Party, the Unitary Democratic Coalition (the former Communist Party) in Portugal, or populist parties like the Five Star Movement in Italy also feature here. With a few exceptions, they are anti-system opposition parties. It is rather unlikely that they will enter power any time soon.

With the exception of the Sweden Democrats, all the parties in this group support closer ties between their country and Russia, oppose sanctions on Russia, or have party contacts with the Russian regime. They want to bring an end to the ‘NATO/EU-centric’ European security order in favour of a system that would suit Russia’s interests. Various media outlets have documented Russian loans to the Front National, and researchers suspect financial links with many more of these parties, although they have not found any proof.[6] The FPÖ and the Lega Nord have agreed cooperation pacts with Vladimir Putin’s ruling party, United Russia.[7]

Moderate anti-Western parties (31 parties)

The Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia (KSCM) in the Czech Republic and Geert Wilders’s Party of Freedom (PVV), ranking 31st and 32nd in the party list, are the first parties one can designate ‘moderate anti-Western parties’. They are anti-Western parties overall (they reject more elements of the Western order than they endorse), but accept some parts of the Western model. For most left-wing parties in this category, like the German Die Linke or the Spanish Unidos Podemos, this includes support for secularism and an open society. Right-wing parties like the Finns Party or Forza Italia accept economic liberalism and the transatlantic link, and they sometimes accept a European security order based on Western institutions. Because the moderate anti-Western parties have some commonalities with the established pro-Western parties, they are much more likely to be invited to join a government.

Apart from more moderate left-wing or right-wing populist parties, several mainstream parties are found in this grouping as well. They include the Austrian Social Democratic Party and Austrian People’s Party, the Slovak Direction-Social Democracy, Fidesz in Hungary, Forza Italia, and Les Republicains in France. In all of these mainstream parties, anti-Western positions are stronger than pro-Western positions. In central Europe, anti-Westernism has strong roots in the political discourse: in Hungary, Austria, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic, many parties share anti-Western ideological patterns. In Italy and France, the political spectrum is divided between pro- and anti-Western forces. In all of these countries, debates about whether the country belonged to the West or would have to embark on a ‘culturally unique path’ to modernisation were strong during the entire twentieth century. The anti-Westernist patterns are to some extent the latest manifestation of this debate. Germany had a similar debate in the past. However, after 1945 it fully embraced the Western model.

The parties in this category: show a preference for close relations with Russia, are in favour of lifting sanctions, and have ties with the Russian regime. The exceptions to this rule are the Finns Party, Centrum (also from Finland), the Südtiroler Volkspartei in Italy, Kukiz’15 in Poland, and the Conservative People’s Party of Estonia. The remaining 26 parties in this category are inclined towards Russian interests.

Moderate pro-Western parties (49 parties)

Parties in this category support more elements of the ‘Western model’ than they reject, although they do reject some of them. This group is very heterogeneous, as the results for different measures vary considerably from party to party, and from country to country. Left-wing parties have reservations about globalisation and free trade, and are sceptical about transatlantic relations and about a European security order which relies on NATO and the EU. Conservative parties, on the other hand, are sceptical about secularism and opening up to non-Christian communities (see below for more on this). Some conservative parties are Eurosceptical in their outlook.

This group features many parties that are currently in government, or recently have been, such as the British Conservative Party, the Parti Socialiste in France, the Partido Popular in Spain, the German Social Democrats, and others.

And within these moderate pro-Western parties is a special subgroup comprising left-wing parties that are completely pro-Western – except when it comes to questions relating to Russia directly. These parties fully embrace the Western model, open societies, free trade, political liberties, social modernisation, and a secular state. But they also promote closer ties or economic cooperation with Russia, easing sanctions at the earliest opportunity, or are equivocal when it comes to how the European security order should be arranged. These parties include the Italian Democratic Party, the Portuguese Socialist Party, the Slovenian Social Democrats, the French Parti Socialiste, the German Social Democrats, the Bulgarian GERB, the Czech Social Democrats, and the Finnish Social Democrats. The parties belonging to this ‘inconsistent left’ group do not support the ideological agenda that the Kremlin promotes in Europe, nor do they promote outright ideological confrontation with the Kremlin over the future of Europe’s political, social, and economic order.

Pro-Western parties (71 parties)

The biggest single group emerging from the study is that which comprises parties supporting Western positions on all issues surveyed. Despite the populist surge and the rise of anti-system parties, this is still the largest group, larger than the two groupings of anti-Western parties put together. Across Europe’s political parties, there still is broad support for the ‘Western model’.

This group also includes some of the most important parties in Europe, such as the German Christian Democratic Union (CDU), La République en Marche! in France, Civic Platform in Poland, the Socialist Party in Spain, and the Social Democratic Party in Portugal. The success of En Marche! in the recent parliamentary election helps shift the political balance in France very much towards the pro-European centre. This pro-Western end of the ranking is largely occupied by liberal parties or bourgeois green parties, which are ideologically closest to the concept of Western universalism.

The data suggests that some western European parties in this group are relatively relaxed about the question of whether or not Russia is a threat. But no party promotes the lifting of sanctions or cultivating ties with the regime. There are no out-and-out pro-Russian parties in this category.

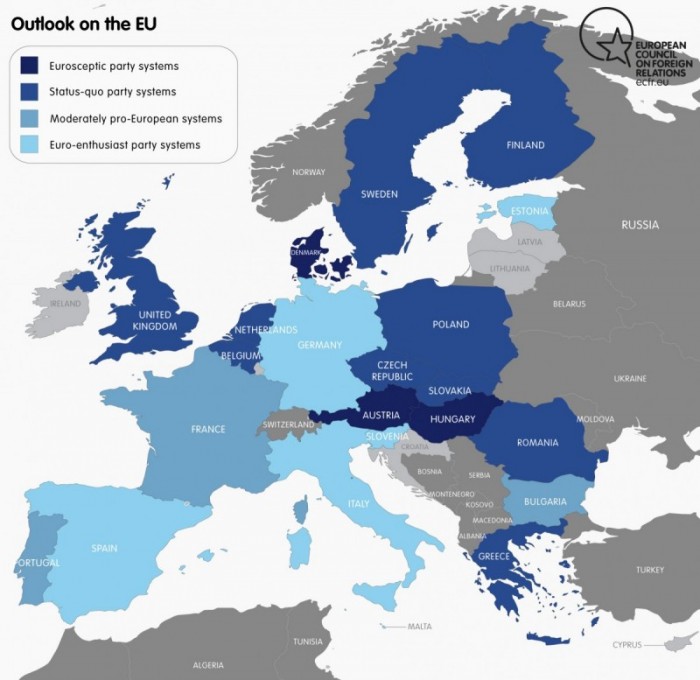

National political systems

The parties, however, are not the end of the story. They exist within national political systems, and it is the balance of parties within each system that determines the overall orientation of the country. Many hardcore anti-Western parties, for example, are small anti-system opposition parties with marginal representation at the national or European level that have little direct influence over political decisions. By contrast, the opportunity for Russia to find friendly faces in the national politics of a country grows significantly once the ideological patterns of mainstream parties begin to align with those of the Kremlin.

Aggregating the results across the parties studied in each individual country can reveal which national political systems have experienced a spread of anti-Western ideological patterns and which have remained resistant to such a spread. This section categorises EU countries according to the patterns of pro- and anti-Western thought in their respective parliamentary systems. As described in the annex, countries were ranked according to a specific index number and then grouped in the same way that the individual parties were. There are four groups: the Anti-Western Stalwarts, the Malleable Middle, the Nordic-Baltic Exceptions, and the Resilient Rest. For the full ranking, see Table 2 in the annex.

The Anti-Western Stalwarts

In five countries – Austria, Bulgaria, Greece, Hungary, and Slovakia – the overall party system tends towards anti-Western positions on most of the 12 questions. This indicates that anti-Western ideologies are deeply rooted in the political system. Anti-system opposition parties – associated with anti-Western thought in most European countries – are even more radical. With the Hungarian prime minister, Viktor Orbán, openly endorsing ‘illiberal’ governance, Hungary leads the ranking of anti-Western party systems in Europe.[8] It is followed closely by Austria. Both are ruled by parties – Fidesz and the Social Democratic Party respectively – that fall into the anti-Western category in the party index. One shared characteristic of the countries in this group is that mainstream and ruling parties, not just fringe parties, show a particular affinity with anti-Westernism. For example, Syriza, the ruling party in Greece, is nearly as anti-Western as Fidesz. The Bulgarian Socialist Party, which recently won the country’s presidency, is the most anti-Western mainstream party in Europe.

Hungary is the EU member state that exhibits the greatest level of disagreement with the liberal order in Europe. It has the highest ranking on Euroscepticism, the strongest scepticism about liberalism and transatlantic relations, and the most negative stance towards European solidarity in the refugee crisis. After Poland it is the second most anti-secular parliamentary system in the EU. On globalisation and free trade, only Austria is more sceptical than Hungary.

The ‘social conservative’ or ‘illiberal’ consensus among the governing parties provides an opening for Russia. Only in Greece is the desire to create closer ties with Russia and to lift sanctions stronger than in Hungary.

Previous studies have identified growing business ties between Russia and the Hungarian government, as well as loopholes enabling corruption, as key facilitators of Russian influence in Hungary.[9] Indeed, the economic and political proximity of Orbán’s government and the Kremlin is well documented.[10] Russian intelligence services see Hungary as a sanctuary and have increased their activities there.[11] But the strong anti-Western political consensus among the Hungarian ruling elites suggests that the country’s close business relations with Russia are the result of a dedicated ideological choice.[12]

In Austria, the political left is the main purveyor of anti-Western discourse, but the growing might of the right-wing FPÖ is contributing further ideological elements. Scepticism of free trade and globalisation are strongest in Austria, and these attitudes are shared by both right-wing and left-wing parties. In fact, Austria is the only EU country that receives an anti-Western score on all 12 questions – although sometimes only marginally so. Its position on Ukraine particularly stands out. Even in deeply anti-Western Hungary, support for Ukraine is a pragmatic exception to the country’s generally anti-Western ideological stance (Ukraine is home to a significant Hungarian minority). No other country in Europe perceives Ukraine to be an obstacle to good relations with Russia in the way that Austria does.

The anti-Americanism visible across all parties in Austria also helps create conditions in which there is sympathy for Russia, particularly on security issues. Austria is, after Greece, the country most dissatisfied with the ‘NATO/EU-centric’ security order in Europe. The research on Austria has focused primarily on the Russian influence on the FPÖ and other extremist groups, although since 2014 various authors have attested to a wider Russian influence on the political mainstream.[13] As one group of authors put it, “[p]ro-Kremlin/anti-sanction voices in the Austrian political debate can be divided into two groups: actors that operate exclusively, or predominantly, based on economic considerations and those located in considerable ideological proximity to Russian power circles. The first group reaches far into the political centre.”[14]

Both Bulgaria and Greece suffered extensively in the economic crisis after 2008, and were key transit countries in the refugee crisis. The countries’ parties have absorbed the backlash into their ideologies, although in different ways. In Bulgaria, the impact of the refugee crisis is clearly visible. Support for the continuation of Assad’s rule as a means to end the Syrian war is the policy issue that most sets Bulgaria apart from the rest of Europe. Other patterns of anti-Westernism include the nativist fear of decadence and decline, the wish for better relations with Russia, opposition to sanctions, and scepticism towards transatlantic relations. However, support for the EU is still relatively strong. Russia’s extensive links to various Bulgarian political and social actors as well as attempts to influence the country have been documented.[15] But, unlike Hungary, the Bulgarian prime minister, Boyko Borisov, has tried to contain Russian influence, often finding himself at odds with Bulgarian business elites.[16] Bulgaria’s decision to deny Russia access to its airspace for its operations in Syria in 2015 underpins Bulgaria’s view that solidarity within the NATO alliance comes first. But the pro-Russian camp in the country has heavily criticised such efforts. These can come at a cost in domestic politics.

In Greece, the pro-Russian agenda is much more dominant. There is greater support for closer ties to Russia and bringing an end to sanctions in Greece than in any other country in Europe. It is the country most sceptical of a European security order based on Western institutions and scepticism against transatlantic links is almost as strong as in Hungary. That said, Euroscepticism is weaker than might be expected, and, despite the refugee crisis, the Greek political mainstream does not campaign on an anti-refugee platform. Still, anti-secular fears and anti-liberal tendencies are present. The close ties of the prime minister, Alexis Tsipras, to Putin have barely drawn comment, primarily because the country is utterly dependent on financial assistance from Europe and Germany in particular. Hence Athens’s freedom of manoeuvre on foreign policy is limited.[17]

In Slovakia, as in most central and eastern European countries, Russian connections to far-right and extremist parties are well documented.[18] And the Slovak prime minister, Robert Fico, has made a number of pro-Russian comments.[19] However, the current government has adopted a double-track strategy. In Brussels, it toes the line of the other EU member states, or even proactively supports Ukraine, for the sake of its own security interests embedded in NATO and the EU. However, because pro-Russian sentiments are popular at home, the same government acts very differently if it speaks to the domestic media. Slovak experts and journalists participating in the survey judge the government to be pro-Russian, based mostly on Fico’s language at home. But it remains to be seen how long this dual approach can be maintained.

The Malleable Middle

In some national political systems, the overall consensus is pro-Western but this consensus is challenged by some mainstream parties adopting anti-Western ideological patterns. In central Europe, the Czech Republic is in this group. Social conservative fears of decline, dissatisfaction with the EU and NATO, and anti-liberal populism are visible in the Czech Republic as well. But as a relatively secular society, the anti-liberal and anti-secular patterns are much less pronounced.[20] Compared to Slovakia, the Czech Republic stands out from other central European party systems because of the range of liberal parties that it hosts.

In France and Italy, the liberal pro-Western camp is even stronger. Across the entire party system, anti-Western ideological patterns are not part of the national consensus. On identity issues, such as support for EU integration, liberal values, secularism, free trade and globalisation, and the refugee crisis, both countries are mostly indifferent to anti-Westernism. Established liberal forces lead the policy discourse on these issues and their stance is strongly pro-Western. But on Russia-related issues, the established liberal forces have fewer consensus views. Hence the anti-Western forces have more leeway to express their views and shape the political debate.

In Italy, Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia is an anti-Western mainstream party. The party holds anti-secular views, is sceptical towards the established European security order, supports deeper ties with Russia and the lifting of sanctions, and opposes immigration, particularly from the Middle East and north Africa. On Forza Italia’s right flank stand even more radical anti-Western opposition parties, which compete for the same electorate: on the extreme right are the Lega Nord and the Fratelli d’Italia, both heavily inclined towards anti-Westernism on all 12 issues. Meanwhile, the populist Five Star Movement promotes the anti-Western agenda from a left-wing perspective.

In France, Russia has fostered ties not only with the extreme right, as is commonly thought.[21] In advance of the French presidential election this year, it was widely expected that victory for François Fillon would be a positive outcome for the Kremlin. Indeed, even the Soviet Union learned to exploit the Gaullists’ anti-Americanism and argued that the USSR needed to be respected as a ‘normal’ great power with legitimate rights.[22] These Russophile attitudes have survived until the present day among the French right, and are now represented by the Les Republicains.[23]

In Italy, however, anti-Western right-wing forces continue to dominate the debate about Russia. As with France, Russia had invested considerable resources into shaping close relationships. The friendship between Putin and Silvio Berlusconi is well known.[24] But the underlying ideological consensus between the right-wing elites and the Russian leadership – sharing the view that both Russia and Italy were both denied their rightful great power status by the West – extends beyond these two individuals. Geopolitical myth-building[25] is amplified by extensive Russian attempts to increase its profile in the country, and has created very favourable conditions for Moscow.[26] With France’s conservative elites out of favour with the electorate, Italy may be expected to move to the centre of Russia’s attention to maintain influence in Europe.

The Nordic-Baltic Exceptions

In the previous groups, the spread of anti-Western ideological patterns coincided with the adoption of pro-Russian stances by anti-Western forces. But some countries, including Finland, Poland, Sweden, and, to a much lesser extent, Denmark find themselves more or less in the middle of the overall ranking and therefore not particularly susceptible to anti-Westernism. However, the study shows that they share a certain amount of Euroscepticism and a certain fear of the loss of their Christian identity. But in none of these countries is establishing closer ties with Russia, lifting sanctions, or altering the European security order to Russia’s liking up for negotiation.

Even individual parties with strong anti-Western sentiments on the right do not embrace Russia. As suggested earlier, these include the Finns Party, Law and Justice (PiS) and Kukiz’15 in Poland, and the Sweden Democrats. The political left is also relatively unsympathetic towards Russia. The Swedish Left Party and the Finnish Left Alliance are marginally inclined towards Russia – but their views are not comparable to the pro-Russian sentiments seen in other western European left-wing parties. Even though mainstream parties in Finland and Poland hold anti-Western positions on questions around secularism and European integration, including the governing parties, the parties in these countries nonetheless broadly believe that Russia is not a potential partner in ensuring the survival of Christianity or finding an alternative order to the EU.

The Resilient Rest

The other national party systems seem rather less open to anti-Westernism, and so it may be more difficult for Russia to influence national debates in those countries: Belgium, Estonia, Germany, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Slovenia, and the United Kingdom. However, this does not mean that anti-Westernism is not present at all or that Russia has no potential partners in these countries.

In the Netherlands, for example, there is an overall consensus that the transatlantic link, free trade, and globalisation are good things. Belief in the value of NATO is strong (including in Geert Wilders’s Freedom Party), but opinion on the EU is quite negative. The Netherlands has the fourth most Eurosceptical party system in Europe, after Hungary, Denmark, and Austria. Identity issues, particularly the fear for the loss of Christian identity and fear of migration, are widespread in the Netherlands. And while public attention focuses on Wilders, he is not the only political figure to bring it up. Russian propaganda also profits from the fear of terror and migration. All parties in the Dutch parliament are open to the argument that Russia is an ally in the war on Islamic terror.

Euroscepticism is the only viable entry-point for Russia’s ideological influence in many of these countries, particularly the UK. Forging permanent structural ties with opposition parties is much more difficult, as the national consensus is less susceptible to the ideology that Russia promotes. Hardcore anti-Western parties, like UKIP, exist but they have only dim electoral prospects. The Brexit referendum was an occasion on which there was a vote on the single anti-Western attitude that is fairly popular in north Europe and separate from other anti-Western stances (opposition to free trade, to NATO, and to the transatlantic link) that a British audience would not accept. No wonder allegations of Russian support for the Brexit campaign appeared early on.[27] However, compared, for example, to the permanent structural influence created through party ties with Italian or Austrian mainstream parties, the Brexit campaign only provided a short – if dramatic – opportunity to exert influence. And even then, Euroscepticism was strong in the UK even without Russian assistance. Moscow may make use of the opportunities that arise, but these are frequently of Europe’s own making.

Finally, it might come as a surprise that Germany is not considered susceptible to Russian influence, given the prominent friendship between Putin and former chancellor Gerhard Schröder, as well as the intensive lobbying for rapprochement and unconditional détente conducted by pro-Russian circles within Germany.[28] However, three years into crisis and war in Ukraine, German political and public attitudes have shifted against Russia, and the findings of this survey have partially demonstrated this shift.

But there are reasons for caution. This survey was carried out at a moment in German politics where resilience against anti-Westernism was probably at its all-time high. For now, the left-wing Die Linke is the only anti-Western party represented in the Bundestag. But the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) is a strongly anti-Western party and is set to enter the Bundestag in the September 2017 election.

One can only speculate as to what effect the AfD will have on German politics once it enters the Bundestag. In Austria, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, France, Finland, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Poland, and Slovakia, where anti-Westernism has penetrated the political mainstream, two or more parties have an agenda inclined towards anti-Western patterns. To some extent, this indicates at least a partial anti-Western consensus within society at large.

But this party configuration may also hint at structural dynamics within the party system. In systems containing just one anti-Western party, the consensus tends to consolidate around pro-Western positions, and anti-Western sentiments are consigned to the extremist fringe (the right wing in the UK or the left wing in Germany, Portugal, and Spain). However, once there is more than one anti-Western party in parliament, they are much more able to push the political agenda in their direction and exert influence over the positions of mainstream parties. In Germany, the conservative CSU’s increasingly favourable stance towards Russia is already a sign of this dynamic at work. The party considers the AfD its main competitor.

Researchers responding to the survey in Germany made extensive use of explanatory answers, reflecting the fact that many different and even opposing opinions are frequently found within one German party. Because of the still relatively compact German party system, the parties contain diverse ideological perspectives. The German Social Democrats house an anti-Western wing, the Greens are split, and in Merkel’s CDU liberal and conservative wings are divided on many issues, particularly EU integration and refugees. However, the mainstream parties’ ability to host such diverse views is in decline. If the Bundestag election this year propels both the AfD and the Free Democrats into the Bundestag, there will be further fragmentation – and, crucially, the potential for a parliamentary make-up that is friendlier to Russia overall.

Anti-secularism: Moscow’s way in?

The most interesting individual topic identified in the study is the debate on ‘secularism’, or the fear of losing Europe’s Christian roots. There was a high response rate to this question and a broad spectrum of views all across Europe. Eight countries have parliamentary systems that tend towards supporting the idea that the loss of Christian identity is a major threat. They are Austria, Bulgaria, Finland, Greece, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Slovakia.

It is the only item in the survey that correlates with the traditional ‘left-right’ divide, with conservative parties more likely to fear the erosion of Christian values (on all other questions, there is no correlation between the spread of answers and whether a party is left-wing or right-wing). Importantly, this attitude does not correlate with the parties’ own broader views on Russia – meaning that many parties sceptical of Russia also subscribe to the narrative that European Christianity is under threat.

From the Kremlin’s perspective this issue may be its best chance of reaching an audience beyond the constituencies already well disposed towards Russia. Moscow already claims to be Europe’s ‘third Rome’, the last Christian bastion. The Kremlin tries to portray its efforts in Syria under the framework of a “common fight against terror”,[29] putting Putin into the role of the defender of Christianity.[30] Russian propaganda seeks to highlight this issue, portraying its competitors in Europe (Germany, Sweden, and particularly Merkel personally) as facilitators of the ‘Islamisation’ of Europe.[31] It remains to be seen how effective these efforts will be. Still, European policymakers should take the challenge seriously and be aware of issues like this that could resonate with the public in both Europe and Russia.

On broader identity issues, established parties need to come up with credible policies on integration that reassure populations that the coexistence of diverse religious communities can be managed under the umbrella of the existing legal and public order. One of the few serious attempts so far to do this has been Austrian foreign minister Sebastian Kurz’s effort to set up a state secretariat for integration in Austria. This first tries to assess the situation and then to tackle the most pressing issues with corresponding legal and administrative actions.[32] One may debate the effectiveness of the measures, or whether the Austrian approach is applicable in other EU member states. But it is the only visible attempt to respond to the challenge posed by anti-Westernists.

With regard to other key topics, despite the current unity within the EU on maintaining sanctions, the research shows that ‘relations with Russia’ and support for sanctions are highly polarising issues in domestic politics. The issue is also inherently divisive across Europe, as national consensuses vary greatly, with Greece the most pro-Russian and Poland the least. There is support for lifting sanctions and creating closer ties with Russia in Greece, Hungary, Austria, Slovakia, Bulgaria, France, the Czech Republic, Italy, and Portugal, while on the other hand Poland, Estonia, the United Kingdom, Romania, Denmark, Sweden, and Germany are sceptical of the possibility of achieving better relations with Russia. For the moment, the sceptical states seem able to hold the line on sanctions. But it is a fragile status quo.

There is a further north-south divide when it comes to support for the EU. Interestingly, Euroscepticism appears to be a minor issue overall, with only five countries’ political systems leaning towards reversing European integration or leaving the EU. However, this is the only issue on which the north is more anti-Western than the south. While support for EU integration correlates most strongly with support for free trade, the European security order and the transatlantic link, there is also a strong relationship between views on EU integration and support for Ukraine. This reinforces the argument that the EU is above all seen as an instrument that safeguards Europe’s security and well-being.

The revolution will be cultivated

This study has for the first time revealed the significant potential overlap of ideology and interests between many European political parties and the Russian government. The focus in recent years has remained very much on parties on the extremes of European politics, even while parties like the Front National accumulated a level of support normally associated with ‘mainstream’ parties. But this research shows that sympathy towards Russia is found within all types of parties, right across the EU. Moreover, such views can spread across national political systems to such an extent that they become the dominant view. Of the 30 radical anti-Western parties for which data is available, 25 seek closer ties to Russia; of the 31 moderate anti-Western parties, 22 do so; of the 49 moderate pro-Western parties, 12 are known to seek closer ties to Russia; and of the 71 fully pro-Western parties only six modestly embrace rapprochement of some kind.

Many Western observers have not fully appreciated the ideological convergence between important European political parties and Russia. But it has likely not escaped Moscow’s notice or that of the parties themselves.

Just as Russia views liberal democracy as inherently flawed and is betting on the long-term weakening of Europe’s established parties as part of this decline, the anti-Westernists see the rise of Russia as an opportunity for them. After 1990, anti-Westernists lacked a credible example to demonstrate that economic modernisation and prosperity were possible without accepting the ‘Western model’, involving a market economy, a liberal democracy, and an open society. Now, anti-Westernists point to Russia and state that another way is possible and that Europe could seek a political, economic, and social order different from the Western liberal model of democracy and market economy. Moreover, every order needs a security provider and Russia could serve as just that.

Of course, as in the cold war, not every fellow traveller is a paid agent of influence. A wide range of motivators – ideological preferences, moral convictions, or opposition to the ‘establishment’, among others – determines party positions. Indeed, ideology is often a more potent influencer than money. One principal benefit that some European parties sense is the feeling of purpose and legitimacy that a relationship with the Russian regime can provide. Both the self-image of Russia’s elites as well as the regime’s official self-justification stress the importance, prestige, and reach of Russia and its power. Russia’s financial resources are far too low to create powerful incentives for all of the actors speaking up on Moscow’s behalf. But, in reaching out to Russia, these parties can show that they have a foreign policy agenda independent from the usual Eurocentric or transatlantic orientation of most parties.

The benefits from the Russian perspective are obvious. As seen with the visits of Italian and German officials to Crimea and Moscow that opened this paper, when the representatives of these parties speak to visiting Russian counterparts or to Russian official media – and repeat the Kremlin’s line – the Russian government can claim to its domestic audience that it is not isolated and that large parts of the European political class support the Russian point of view.[33]

Despite the victory of Emmanuel Macron in the French presidential election, the anti-Western revolt has not yet run its course. Allegations of Russian meddling, influencing, financing, supporting, or cultivating relations with anti-Western parties will not fade away. This does not mean that Russia is intentionally creating opportunities to disrupt European policymaking all the time. Rather, these opportunities will present themselves to Russia to use according to the situation and the tactical considerations of the moment. Russia did not cause the recent ideological revolt in Europe, but it may yet be its main beneficiary.

Forging ties with anti-Western parties will remain a long-term interest for Russia. These connections suggest that Moscow has the capacity to improve its image and popularity among large segments of the European population. This would increase Russia’s ability to shape political discussions beyond the range of its conventional power resources. Economically and culturally, Russia’s ability to influence the course of events in Europe is limited. Ideologically, however, Russia can play the role of leader.

In response, European politicians who are pro-Western need to actively counter the ideological threat that Russia and its apologists represent. Strengthening counter-intelligence services, tightening anti-corruption legislation and supervision, strengthening anti-trust laws and strictly implementing the third energy package would make it more difficult for Russia to develop and exploit its various channels of influence.

Above all, such steps would make it harder for Russia to cultivate the established political and economic elites, which are more influential than marginal populist parties. They will not see off the existence of anti-Western dissent within Europe, but they will make it much more difficult for Russia to make use of the openings this dissent creates.

And, finally, to address the problem, we need first to name it. We now know that anti-Western elements, capable of being exploited by the Kremlin, exist not only on the fringes of European politics, but can be found at the heart of Europe’s established political parties. It is up to politicians of pro-Western parties, especially ‘mainstream’ ones, to spot such trends, show leadership and halt the drift towards a place where liberal democracy transforms itself into something rather less open.

[1] James Politi and Max Seddon, “Putin’s party signs deal with Italy’s far-right Lega Nord”, 6 March 2017, Financial Times, available at https://www.ft.com/content/0d33d22c-0280-11e7-ace0-1ce02ef0def9?mhq5j=e1.

[2] Russische Medien begrüßen den “Gegner der Kanzlerin”, Deutschlandfunk, 3 February 2016, available at http://www.deutschlandfunk.de/seehofer-in-moskau-russische-medien-begruessen-den-gegner.1773.de.html?dram:article_id=344436; Wie russische Medien Seehofer instrumentalisieren, Die Welt, 3 February 2016, available at https://www.welt.de/politik/ausland/article151796449/Wie-russische-Medien-Seehofer-instrumentalisieren.html.

[3] Philip Oltermann, “Bavarian leader lashes out at Merkel’s handling of refugee crisis”, the Guardian, 10 February 2016, available at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/feb/10/bavarian-leader-horst-seehofer-lashes-out-merkels-handling-refugee-crisis.

[4] Richard Herzinger and Hannes Stein, “Endzeit-Propheten oder Die Offensive der Antiwestler. Fundamentalismus, Antiamerikanismus, und die Neue Rechte“, Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag GmbH, Reinbeck bei Hamburg, April 1995.

[5] See “Germany and Russia: How Very Understanding”, The Economist, 8 May 2014, available at https://www.economist.com/news/europe/21601897-germanys-ambivalence-towards-russia-reflects-its-conflicted-identity-how-very-understanding.

[6] See, for example, Gabriel Gatehouse, “Marine Le Pen: Who’s funding France’s far right?”, BBC Panorama, 3 April 2017, available at http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-39478066.

[7] “Putin’s Party Signs Cooperation Deal with Italy’s Far-Right Lega Nord”, the Daily Beast, 6 March 2017, available at http://www.thedailybeast.com/cheats/2017/03/06/putin-s-party-signs-cooperation-deal-with-italy-s-far-right-lega-nord.html; “Austria’s Far Right Signs a Cooperation Pact With Putin’s Party”, the New York Times, 19 December 2016, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2016/12/19/world/europe/austrias-far-right-signs-a-cooperation-pact-with-putins-party.html?_r=0.

[8] “Defying Soviets, Then Pulling Hungary to Putin, Viktor Orban Steers Hungary Toward Russia 25 Years After Fall of the Berlin Wall”, the New York Times, 7 November 2014, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/08/world/europe/viktor-orban-steers-hungary-toward-russia-25-years-after-fall-of-the-berlin-wall.html?_r=0.

[9] Heather A Conley, James Mina, Ruslan Stefanov, Martin Vladimirov, “The Kremlin Playbook: Understanding Russian Influence in Central and Eastern Europe”, Center for Strategic and International Studies, October 2016, available at http://www.csd.bg/fileadmin/user_upload/160928_Conley_KremlinPlaybook_Web.pdf (hereafter, Heather A Conley et al, “The Kremlin Playbook”).

[10] See Dániel Hegedűs, “The Kremlin’s Influence in Hungary, Are Russian Vested Interests Wearing Hungarian National Colors?”, DGAP Kompakt, Nr.8/2016, available at https://dgap.org/en/article/getFullPDF/27609.

[11] Hungarian secret agent reveals in detail how serious the Russian threat is, Index.hu, 21 March 2017, available at http://index.hu/belfold/2017/03/21/hungarian_secret_agent_reveals_how_serious_the_russian_threat_is/.

[12] Preliminary evidence also supports this conclusion. See: “Súlyos visszaélések voltak a moszkvai magyar konzulátuson”, Index.hu, 8 February 2017, available at http://index.hu/belfold/2017/02/08/brutalis_visszaelesek_voltak_a_moszkvai_magyar_konzulatuson/.

[13] Bernhard Weidinger and Fabian Schmid, “Austria”, in: Péter Krekó, Lóránt Győri, Edit Zgut (ed.), From Russia With Hate: The activity of pro-Russian extremist groups in central and eastern Europe, (Political Capital Kft: 2017), p.35.

[14] Bernhard Weidinger, Fabian Schmid, Dr Péter Krekó, “Russian Connections of the Austrian Far-Right”, Political Capital, 27 April 2017, available at http://www.politicalcapital.hu/pc-admin/source/documents/PC_NED_country_study_AT_20170428.pdf.

[15] Heather A Conley et al, “The Kremlin Playbook”.

[16] Dimitar Bechev, “Russia’s Influence in Bulgaria”, New Direction, 24 February 2016, available at http://europeanreform.org/files/ND-report-RussiasInfluenceInBulgaria-preview-lo-res_FV.pdf; John R Haines, “The Suffocating Symbiosis: Russia Seeks Trojan Horses Inside Fractious Bulgaria’s Political Corral”, Foreign Policy Research Institute, 5 August 2016, available at http://www.fpri.org/article/2016/08/suffocating-symbiosis-russia-seeks-trojan-horses-inside-fractious-bulgarias-political-corral/.

[17] Henry Stanek, “Is Russia’s Alliance with Greece a Threat to NATO?”, the National Interest, 17 July 2016, available at http://nationalinterest.org/feature/russias-alliance-greece-threat-nato-16998.

[18] Grigorij Mesežnikov, Radovan Bránik, “Hatred, violence and comprehensive military training: The violent radicalisation and Kremlin connections of Slovak paramilitary, extremist and neo-Nazi groups”, Political Capital, 5 April 2017, available at http://www.politicalcapital.hu/pc-admin/source/documents/PC_NED_country_study_SK_20170428.pdf.

[19] “EU should drop Russia sanctions, Slovak PM says after meeting Putin”, Reuters, 26 August 2016, available at http://www.reuters.com/article/us-ukraine-crisis-slovakia-idUSKCN1111A1.

[20] However, it is still present, and exploited by the Kremlin. See Sofia Voznaya, “The Czech Republic’s Phantom Muslim Menace”, Coda, 15 February 2017, available at https://codastory.com/disinformation-crisis/information-war/the-czech-republic-s-phantom-muslim-menace.

[21] Jean-Yves Camus, “A Long-lasting Friendship: Alexander Dugin and the French Radical Right”, in: Marlene Laruelle (ed.), Eurasianism and the European Far Right, Reshaping the Europe-Russia Relationship, (Lanham, Boulder, New York, London: Lexington Books, 2015), pp.79-96.

[22] Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin, The Mitrokhin Archive: The KGB in Europe and the West, (Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin Books, 2000), pp.613-618.

[23] Alina Polyakova, Marlene Laruelle, Stefan Meister and Neil Barnett, “The Kremlin’s Trojan Horses: Russian Influence in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom”, the Atlantic Council, November 2016, available at: http://www.atlanticcouncil.org/images/publications/The_Kremlins_Trojan_Horses_web_0228_third_edition.pdf, p.7. (hereafter, Alina Polyakova et al, “The Kremlin’s Trojan Horses”).

[24] Alan Friedman, “Silvio Berlusconi and Vladimir Putin: the odd couple”, Financial Times, 2 October 2016, available at https://www.ft.com/content/2d2a9afe-6829-11e5-97d0-1456a776a4f5.

[25] For examples see the Limes geopolitical review. The review maintains both the anti-American myth of Washington seeking to destroy a supposed German-Russian alliance through ‘expanding’ to the ‘buffer-states’ of eastern Europe as well as the myth of ‘natural’ Russian interests in the neighbourhood. See http://www.limesonline.com.

[26] “With Italy No Longer in U.S. Focus, Russia Swoops to Fill the Void”, the New York Times, 29 May 2017, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/29/world/europe/russia-courts-italy-in-us-absence.html.

[27] Nico Hines, “Why Putin Is Meddling in Britain’s Brexit Vote”, the Daily Beast, 8 June 2016, available at http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2016/06/08/why-putin-is-meddling-in-britain-s-brexit-vote.html.

[28] Stefan Meister, “Interdependence as Vulnerability”, in Alina Polyakova, Marlene Laruelle, Stefan Meister, Neil Barnett (ed.), the Kremlin’s Trojan Horses: Russian Influence in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom, the Atlantic Council, November 2016, available at: http://www.atlanticcouncil.org/images/publications/The_Kremlins_Trojan_Horses_web_0228_third_edition.pdf, p.12-17.

[29] Somini Sengupta and Neil MacFarquhar, “Vladimir Putin of Russia Calls for Coalition to Fight ISIS”, the New York Times, 25 September 2015, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/29/world/europe/russia-vladimir-putin-united-nations-general-assembly.html?_r=0.

[30] Giulio Meotti, “Putin’s Russia claims the role of defender of Christians under Islam”, Geller Report, 24 April 2014, available at http://pamelageller.com/2017/04/russia-christians-islam.html/. See also “Russia – a game changer for global Christianity”, RT, 11 November 2015, available at https://www.rt.com/op-edge/321447-christians-isis-religion-putin/.

[31] For a specific example of Russian messaging on this issue, see “German economy collapse inevitable, caused by migrant waves – MEP”, RT, 18 September 2015, available multiple examples of https://www.rt.com/shows/sophieco/315811-refugees-influx-german-economy/. However, there are many disinformation attempts. For a broader overview of Russian disinformation see “A Powerful Russian Weapon: The Spread of False Stories”, the New York Times, 28 August 2016, available at https://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/29/world/europe/russia-sweden-disinformation.html; or Tim Hume, “Germany struggles to fight anti-migrant fake news amid fears it could influence its election”, Vice News, 2 February 2017, available at https://news.vice.com/story/germany-fake-news-election-migrants.

[32] For more on the Austrian secretariat for integration and related activities, see https://www.bmeia.gv.at/integration.

[33] For illustrative examples, see “Ein Tag im russischen Staatsfernsehen”, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 19 May 2014, available at http://www.faz.net/aktuell/feuilleton/medien/ein-tag-im-russischen-staatsfernsehen-12944596.html?printPagedArticle=true#pageIndex_2.

By Gustav Gressel, for European Council of Foreign Relations

Dr. Gustav Gressel is a Senior Policy Fellow on the Wider Europe Programme at the ECFR Berlin Office