At the end of the 19th century, Ukrainian was the third most widely spoken language in Odesa, after Russian and Yiddish. According to the 1897 Russian Empire General Census, 37,925 inhabitants of Odesa declared Ukrainian as their mother tongue.

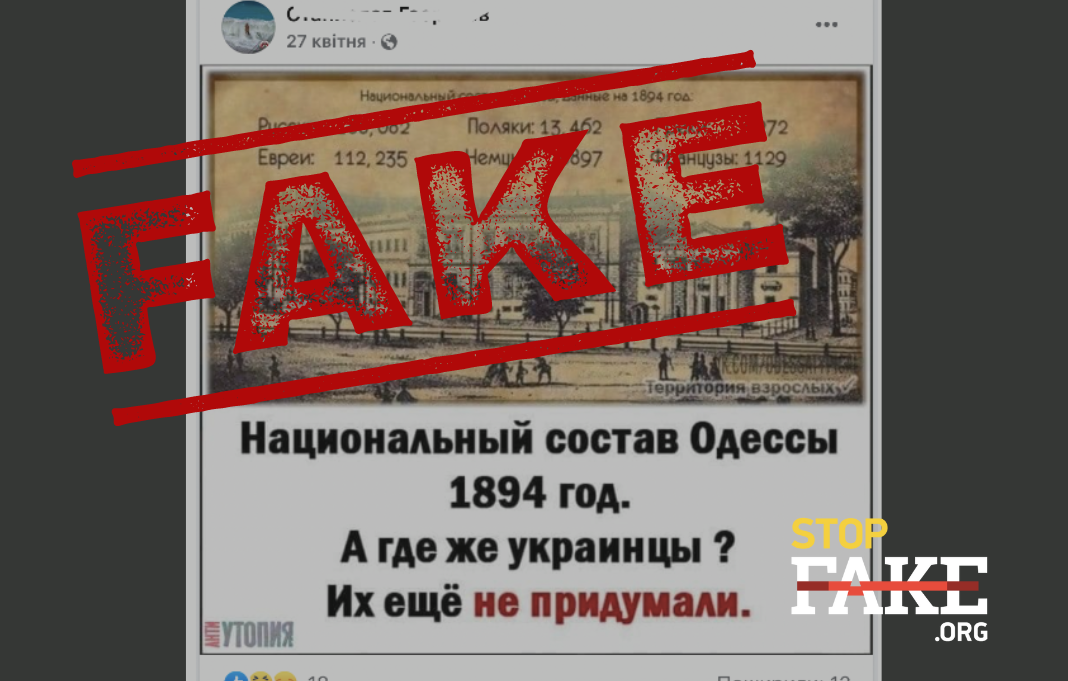

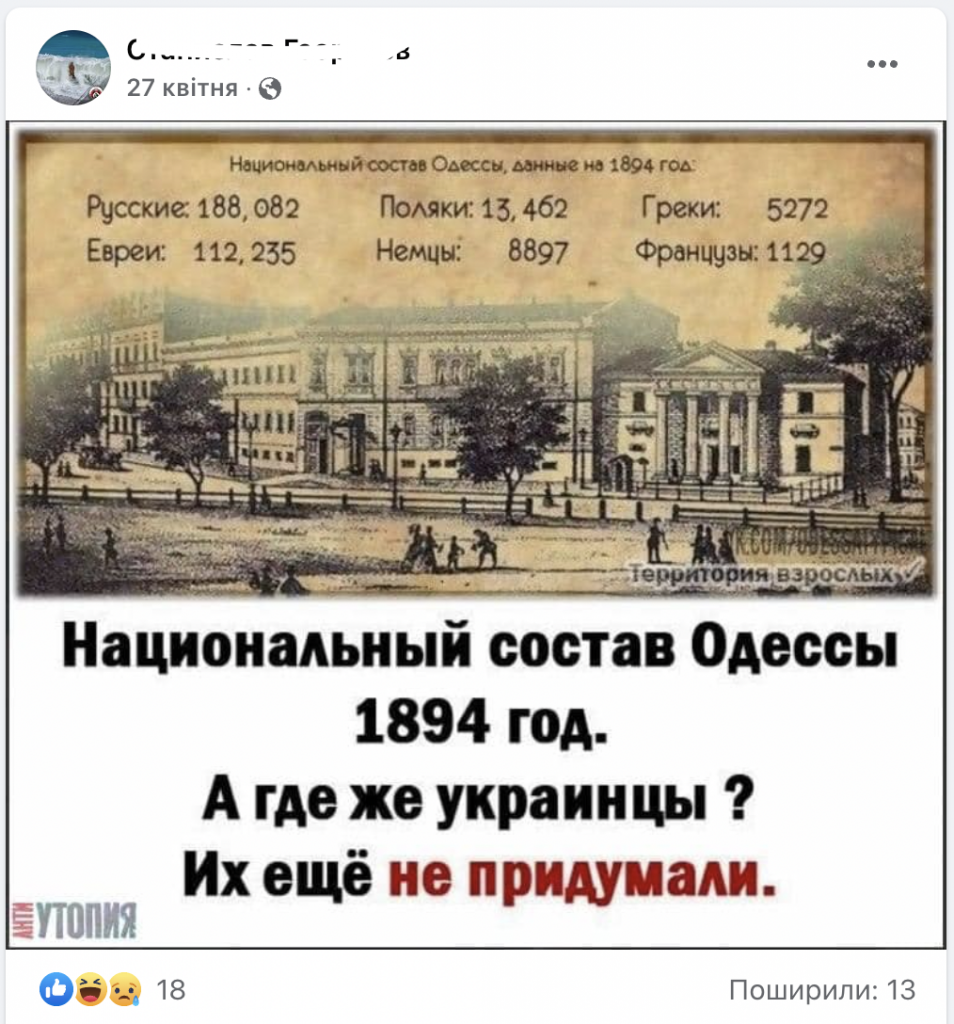

An image of an old postcard featuring an Odesa street with data on the alleged ethnic composition of the port in 1894 is actively being shared on social media. According to the image, the nationalities living in Odessa at that time were Russians, Jews, Poles, Germans, Greeks and French. “Where are the Ukrainians? They haven’t been invented yet!” the post card reads. Another version of this image, with the inscription “Before the October Revolution of 1917, there was no Ukrainian nation in Odesa” is also being circulated on social media.

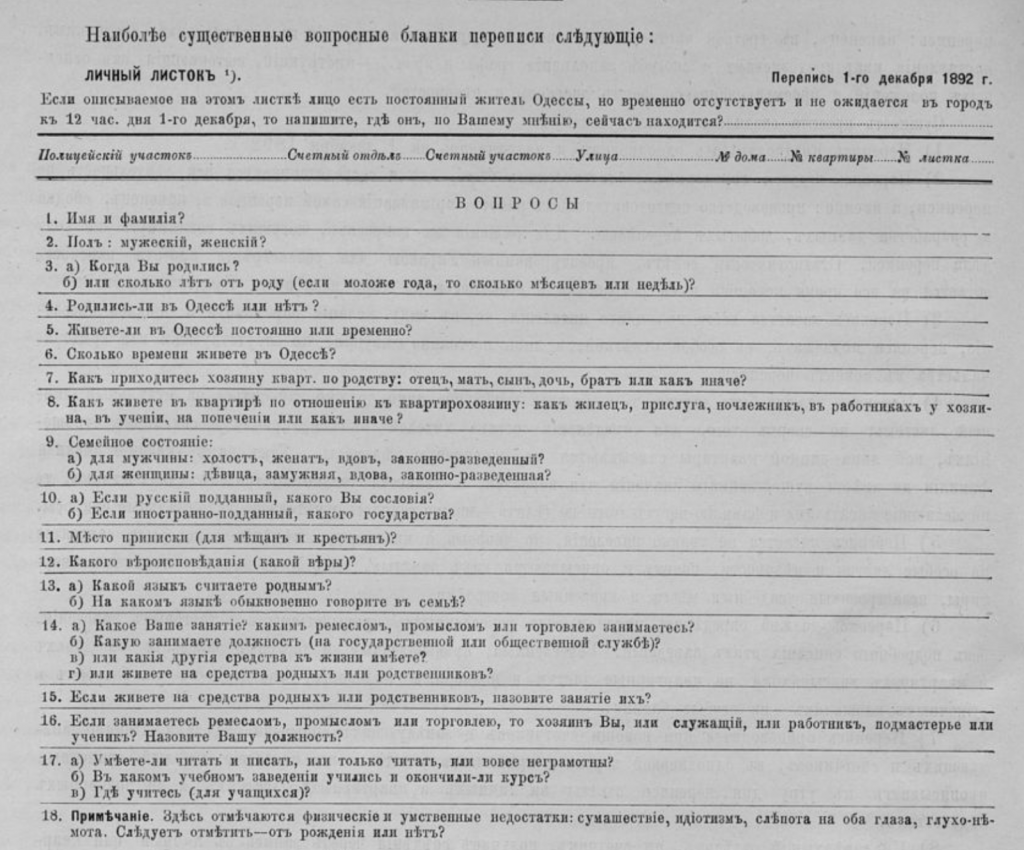

The ethnic breakdown of Odesa presented on this picture more or less correspond with the census conducted in Odesa in 1892, the results being published two years later, in 1894. At that time Odesa had a population of 365,000.

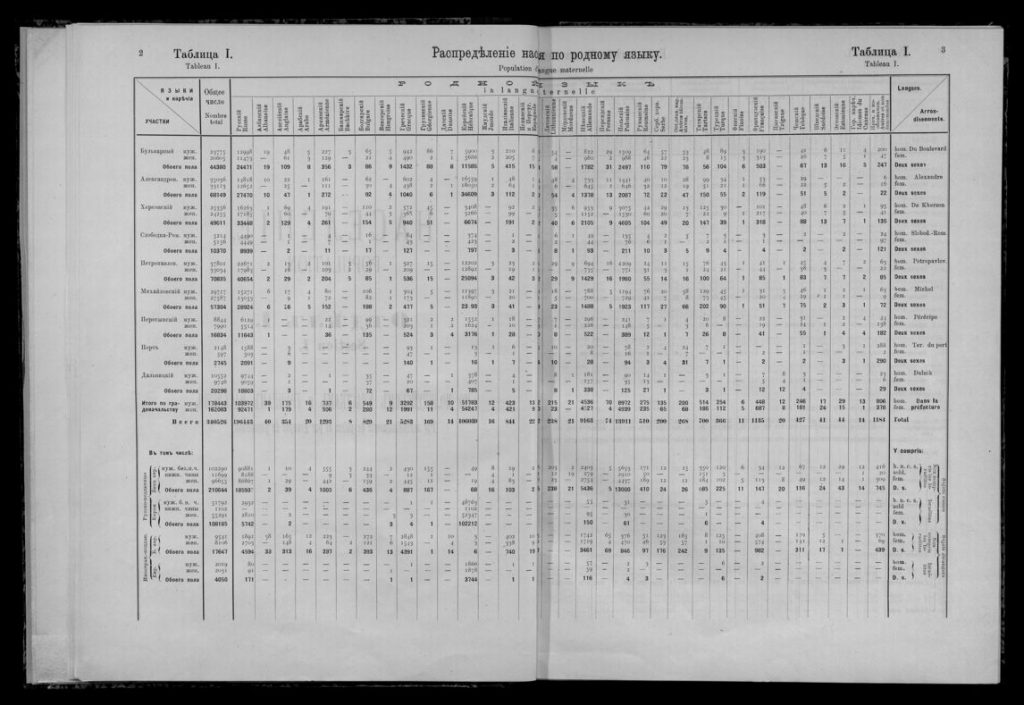

The population was designated according to several parameters, such as native language, religion, whether the person was a Russian citizen or a foreigner. The published census results (volume 1, Population) also featured the questionnaire used, there is no single, specific question about nationality. After all, in the 19th century identity was determined to a great extent through the language of communication and religion. According to the published census data 196,336 Odesa residents spoke the “Russian language”, 106,030 spoke the “Jewish language” and 13,911 spoke the Polish language.

The final census statistics did not distinguish the Ukrainian and Belarusian languages from Russian. This is not surprising because in the 19th century, Ukrainians, or Little Russians as they were called in the Russian empire, were considered to be one of the branches of the “Russian people” which included the “Great Russian” and the “Belarusians”. Harvard Historian Serhii Plokhy in his Lost Kingdom: The Quest for Empire and the aking of the Russian Nation discusses how national politics were formulated in the Russian Empire, using the histories of conquered nations to shape Russian identity, and how Russian propaganda reaches into the imperial past to build its contemporary fake narratives about “Russian unity”.

There is no doubt that in the 19th century Ukrainians were residents of Odessa and inhabited the so-called “Novorossiya” (the Black Sea coast Russia conquered from the Turks and Tatars). There is ample evidence of their presence.

Odesa historian Oleh Gava writes that according to the results of the first 1718 population census in the Russian Empire, 85% of the inhabitants of “Novorossiya” were Ukrainians. And although the number of Ukrainians in the south of Ukraine gradually decreased, until the very end of the existence of the Russian empire, Ukrainians made up more than 70% of the population of the entire region.

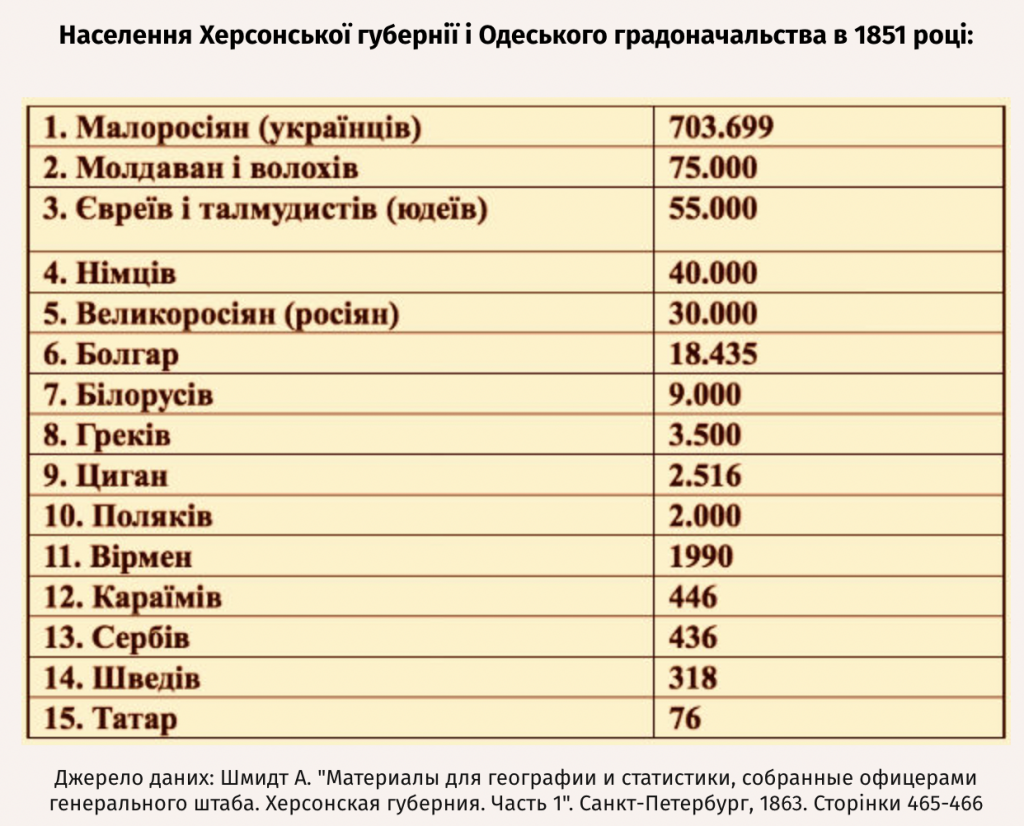

According to military statistician A. Shmidt, a Russian Empire General Staff colonel, in 1851 there were more than 703,000 “Little Russians” (about 70%) in the Kherson province, including the Odesa city authorities, that is, Ukrainians, and 30,000 “Great Russians” – about 3%.

As Odesa historian Oleg Gava points out, from the time of its creation (1802) to the end of the “tsarist times” (1917), the overwhelming majority – up to 3/4 of the total population of Kherson province, which included Odesa, – were Ukrainians. This is reflected both in the data compiled by Colonel A. Shmidt and in provincial reports.

In 1897 the Russian Empire conducted a general population census. According to the obtained data, at that time, 1,462,039 Ukrainians lived in the Kherson province, making up some 53.5% of the total population of the region. At that time, Odesa had a population of 403,815. Also, at the time of the census, more than half of Odesa’s population consisted of people who were not born in the city. They came to Odesa from other Ukrainian provinces.

According to the General Census data, 237,425 residents of Odesa named Russian as their native language. The census documents also indicate that out of these 237,425, 198,233 people spoke Russian directly, 37,925 spoke Ukrainian, and 1,267 spoke Belarusian. In her book Odessa Recollected, the historian Patricia Herlihy calculated that Ukrainian was spoken in Odessa by 5.66% of the population, 50.78% spoke Russian and 32.50% used Yiddish.

As we have already noted, for statistical purposes, nationality was determined by the spoken language. Nevertheless, the historian Ivan Pantyukhov in his work Population of the City of Odessa (1885) calculated that by 1880, a third of all surnames of families living in Odessa were “Little Russian”, that is, Ukrainian, they ended in -tsky, -sky , -ich, -ov, -in. Historian Patricia Herlihy believes that other ethnic groups most likely called Russian their native language in order to identify themselves with the politically dominant group.

The Kremlin propaganda machine uses the narrative that the south-east of Ukraine, the so-called “Novorossiya”, is part of the “Russian world” ito legitimize its aggressive and imperial policy towards Ukraine. Previously, StopFake analyzed similar propaganda narratives in detail in the material Modern Kremlin Mythology: How Russia Uses History in Propaganda.