With fake online news dominating discussions after the US election, Guardian correspondents explain how it is distorting politics around the world

Germany

The German political mainstream is getting increasingly nervous about the effect that the rise of fake news might have on federal elections next autumn. Fake news and Russian interference – either by influencing fake news sites, or by hacking or misinformation – are viewed as a serious threat to the democratic process, particularly since the US presidential elections.

From rumours that Merkel was in the east German secret police, the Stasi, to others suggesting she is Adolf Hitler’s daughter, Germans are also proving themselves susceptible to false information.

The most blatant example of fake news to hit Germany so far occurred earlier this year over reports that a 13-year-old girl of Russian origin, known as Lisa F, had been raped in Berlin by refugees from the Middle East. The story received extensive coverage on Russian and German media who reported the allegations that she had been abducted on her way to school and gang-raped. The attack turned out to have been fabricated, as Berlin’s chief of police was quick to point out. According to Berlin’s public prosecutor’s office the girl had spent 30 hours with people known to her, and a medical examination proved she had not been raped.

But having been shared widely on social media and through Russian news sites, hundreds took to the streets to protest at the “attack”, along with far right and anti-Islam groups. Sergey Lavrov, Russia’s foreign minister went so far as to accuse Merkel’s government of “sweeping the case under the carpet”, heightening suspicions in Berlin that the Kremlin was deliberately trying to cause trouble.

There are suspicions that the story was spread in the first place by Russian elements keen to undermine the refugee policy of Angela Merkel. She is viewed as a key enemy to Russia over her tough stance on Ukraine. The ultimate aim is said to be to destabilise her domestically just as she has said she will stand for a fourth term in office.

In an interview with Der Spiegel magazine Hans-Georg Maaßen – the head of the BfV, Germany’s domestic security agency, – accused Russia of using KGB-style techniques of misinformation.

Addressing the Bundestag on the subject last week, Merkel said: “Today we have fake sites, bots, trolls – things that regenerate themselves, reinforcing opinions with certain algorithms, and we have to learn to deal with them.”

Fake news has also spread to neighbouring Austria and been used to discredit both candidates in this weekend’s presidential election. Most startling have been the attacks on the Green-backed independent candidate Alexander van der Bellen, whose opponents have attempted to spread the news that he is suffering from dementia and is gravely ill.

Kate Connolly

France

Over the last 10 years, France has seen a sharp increase in the readership of alternative, far-right sites, blogs and social media operations, referred to collectively as the fachosphère – (“facho” is slang for fascist). Promoting views including anti-immigration, nativism and ultra-nationalism, these sites are run independently, rather than by a political party. But they feed into a mood of distrust of the traditional media, both on the far right and the far left.

Samuel Laurent, head of Le Monde’s fact-checking section, Les décodeurs, said: “In France, there isn’t a wide presence of totally invented fake news that makes money through advertising, as seen in the US.” But he said France was seeing increasing cases of manipulation and distortion, particularly during election periods.

One example, in the recent primary race to choose the French right’s presidential candidate, was a campaign on the fachosphère to claim the centre-right candidate Alain Juppé was linked to the Muslim Brotherhood. The accusation dated back to local elections in 2014 when distorted stories circulated on a far-right opinion website, accusing Juppé of wanting to build a “Mosque-Cathedral” in Bordeaux, where he is mayor. The story grew and was embellished during the primary campaigns to portray Juppé as a Muslim Brotherhood-linked “Ali Juppé”. Juppé said a “disgusting campaign” had been run against him.

Laurent said: “I think the French presidential election campaign [next spring] will be fraught with this type of thing.” In January, as the presidential election campaign prepares to kick off, Le Monde’s Les décodeurs will launch a database of questionable sites that portray themselves as information sites.

The recent Paris terrorist attacks were also subject to conspiracy theories and distortions, including reports this summer that gunmen who killed 90 people at a rock gig at the Bataclan last November had mutilated their victims. These reports cited partial evidence to a parliamentary inquiry into the attacks, without adding that the inquiry also heard officials deny that any mutilation took place.

There is also an ongoing row over fake information websites about abortion in France. The lower house of the French parliament has approved government plans to ban fake abortion information websites which masquerade as neutral, official sites with free-phone helpline numbers but which the government said promote anti-abortion propaganda and pressure women not to terminate pregnancies.

The women’s minister, Laurence Rossignol, told parliament on Thursday that anti-abortion groups in France were setting up sites “that appear neutral and objective” and copy official government information sites but were “deliberately seeking to trick women”.

She said these sites often had helplines run by “anti-choice activists with no training who want to make women feel guilty and discourage them from seeking an abortion.”

Angelique Chrisafis

Myanmar

A Burmese friend recently put it like this: in the old days, people went to the tea shop to get their news. Now, they go to Facebook.

After decades of isolation under successive military regimes, Myanmar’s 51 million people began to come online rapidly in 2014 after telecoms reforms. They leapfrogged the era of dial-up and desktops, starting with mobile phones and social media. For many, Facebook is synonymous with the internet.

With scores of voices clamoring to be heard for the first time, it’s a dynamic, sometimes dangerous space.

As well as “#foreveralone” statuses and a barrage of updates from staunchly Facebook-first media organizations, news feeds are crammed with fake content. Much of it is tinged with religious hatred. With tensions between the majority Buddhist and minority Muslim populations running high, many are ready to believe vitriolic nonsense about Islam and its followers, often propagated by nationalist accounts set up for the purpose.

A Muslim journalist was recently the victim of a campaign by some of these accounts, when a widely followed nationalist posted pictures of him juxtaposed with images of an unknown Rohingya Muslim militant. The post claimed he was involved in attacks on border police and called for his immediate arrest.

Nothing happened – the post was eventually taken down, though not before more than 3,000 people shared it. But the episode was a hint of the frightening power that fake news can have in a context like Myanmar.

Poppy McPherson

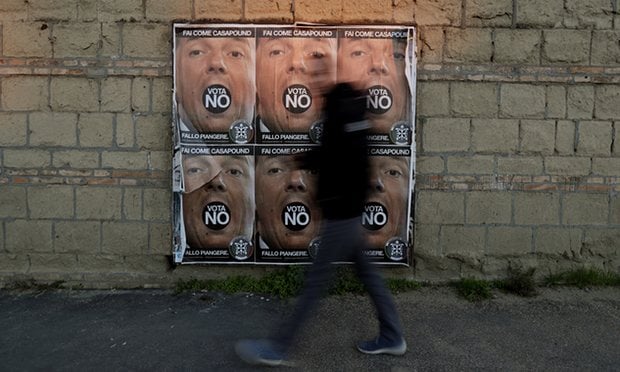

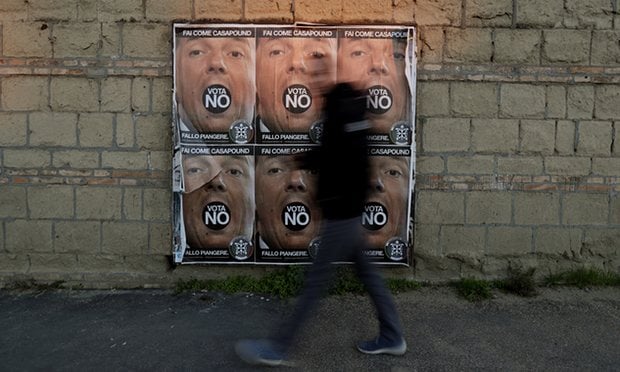

Italy

In Italy, the spread of propaganda has become such a worry for the government that a top official in prime minister Matteo Renzi’s circle of advisers recently filed a defamation complaint against a mystery Twitter account – it has since disappeared – who tweeted under the name “Beatrice di Maio” and routinely took aim at Renzi’s government.

In one example, the Twitter account showed a picture of Elena Boschi, the reform minister, on the phone. It suggested she was sharing insider information with her father, who was a top executive at Banca Etruria, a Tuscan bank. The bank was rescued by the Italian government in 2015 but there is no evidence that Boschi helped her father or committed wrongdoing.

In Italy the attacks against Renzi have been stepped up ahead of the critical 4 December referendum. In some cases, news about Italy reported by Russian state-controlled website RT Today has been especially skewed against the prime minister. In one case highlighted by La Stampa, the Italian daily, the Russian website falsely claimed that a rally in Rome held by supporters of Renzi ahead of the referendum were actually his opponents. The story has since been removed.

Members of Renzi’s Democratic party have complained that “mud-slinging” websites controlled by the anti-establishment Five Star Movement, which abhors traditional political advertising, are to blame for spreading false and defamatory news about the government’s activities.

Stephanie Kirchgaessner

China

As reports emerged that fake news had influenced the US presidential election, China trumpeted its system of a “internet management”, portraying freedom of speech as broken when it can affect the outcome of an election.

“China is on its way to strengthening internet management,” said an editorial in the Global Times, a tabloid affiliated with the Communist party mouthpiece People’s Daily. “The western democratic system appears to be unable to address” the problems and conflict unleashed by the internet, the paper added.

The fake news that spread on Facebook in the run-up to the election even spread to China. Articles originally posted on pro-Trump websites, including Breitbart, were directly translated into Chinese and shared on the country’s social media platforms.

Problems with fake news and fraudulent reporters have existed for over a decade in China, with people often presenting themselves as journalists and threatening companies with negative coverage in an attempt to extort money.

In one high-profile case, a journalist was paid more than $70,000 to write negative stories about a construction equipment manufacturing company, sending its shares tumbling.

But the authorities have seized on the phenomenon as a justification to censor a wide-range of content. In 2013, the government launched a crackdown on online “rumour-mongering” targeting influential users on the Twitter-like website Sina Weibo, but it was widely seen as an attempt to stem criticism of the ruling Communist party.

More recently, Chinese authorities have clamped down on “fake news” they feel harms social cohesiveness, targeting “rumours” that affected property prices in Shanghai or stories the government says increase antagonism between urban and rural residents.

Earlier this year China’s cyberspace administration issued new rules designed to curb the number of stories using information culled from social media, stating “it is forbidden to use hearsay to create news or use conjecture and imagination to distort the facts”.

News outlets cannot use information posted on social media without prior approval, it said.

More recently a top official at the administration suggested there should be a database to identify internet users’ true identities so they could be “rewarded and punished”.

China maintains extensive control over the internet and many foreign websites, including Facebook, Google, Twitter and YouTube, are all blocked by a government program known as “the Great Firewall”.

The country’s vast censorship system that imposes media blackouts on topics ranging from missteps by China’s leadership to investigating corruption cases. A recent directive banned websites from live streaming coverage of the US election.

Benjamin Haas

Brazil

Brazil has a growing problem with fake news and its importance has grown as political opinion polarized following the close re-election victory of leftist president Dilma Rousseff in 2014 and her controversial impeachment in August this year.

According to a BBC Brasil report from April 2016, as the impeachment process that Rousseff and her supporters called a politically motivated coup began heating up, three out of the five most shared news stories on Facebook were false.

A story shared by the Pensa Brasil (Think Brasil) site that falsely said that federal police wanted to know why Rousseff had given 30bn reais ($9bn) to the giant meat company Friboi came third in the ranking with 90,150 shares.

Last year Brazilian journalist Tai Nalon left her job at the Folha de S Paulo, one of Brazil’s leading newspapers, to found the site Aos Fatos (To The Facts) – Brazil’s first fact-checking site.

“There is a lot of false news,” Nalon said in an email interview, “but I would be cautious about saying the problem is similar to what happens in the USA”. Instead, she said there are politically motivated pages that reinterpret and distort existing stories from big news outlets and that much of what they share is more biased opinion than pure falsehood.

But plenty of false stories do circulate on Brazil’s garrulous internet.

The two-year investigation into the Petrobras scandal, called Operation Car Wash, was a key driver in Rousseff’s impeachment. Although she has never been accused of graft, many in her party have been and the scandal prompted huge street demonstrations calling for her removal.

BuzzFeed Brasil this month published this story about how more false news about the operation has been published than real. This year, the 10 most popular false news stories about Car Wash were shared 3.9m times, BuzzFeed said, citing Facebook data. The 10 most popular real stories were shared 2.7m times.

Dominic Phillips

Australia

Fake news is not a problem of any scale in Australia: the media market, dominated by a handful of key players serving a population of just over 21 million people, does not seem fragmented enough.

But Australia is not immune to issues with untruths spreading on Facebook. Over half the population (13.3 million as at end of June) is connected to the internet; of that number, more than half is believed to be active on Facebook.

Some issues seem to be more of a lightning rod for untruths in Australia than others. The link between the halal certification industry and terrorism – repeated by politicians despite a lack of evidence – was so persistent that an inquiry was held late last year.

Concerns over halal certification – often failing to completely mask rampant Islamophobia – flourished on Facebook, even after the inquiry found there was no basis to the connection.

The Boycott Halal in Australia group has close to 100,000 members on Facebook. In November 2014, it shared a satirical news article, apparently under the impression it was true. The post was subsequently deleted, but the page is a hotbed for views that have no basis in fact, as is the page for supporters of the Q Society, which bills itself as “Australia’s leading Islam-critical movement”.

Pauline Hanson, a fringe figure in rightwing politics who is outspoken against Islam, was re-elected to the senate in the federal election in July with support that surprised many pundits. Her One Nation party took four seats in the 76-strong senate this year and the party is expected to do well in the Queensland state elections.

Parallels have been drawn between her return to politics and Trump’s election: both have embraced social media, where they have significant followings, and are similarly unfazed by evidence.

In August, research showed 62% of voters agreed with the statement: “I might not personally agree with everything she says but she is speaking for a lot of ordinary Australians.”

She is active on Facebook, as are many of her supporters. She recently announced that the majority of her press releases would be released only on Twitter.

Elle Hunt

India

After India’s prime minister announced the introduction of a new, 2,000-rupee note last month, phones around the country lit up with the news the bill would come installed with a surveillance chip, linked to a satellite that could track the notes even 120 metres underground.

The claims, debunked by the country’s reserve bank, nonetheless spread like fire over Whatsapp – which has more than 50 million users in India – and migrated into mainstream news.

As in the United States and elsewhere, increasing numbers of Indians are getting their news from social media.

But the 2,000-rupee episode illustrates the deeper impact of fake news in a country where media is prolific, but journalistic standards, especially in regional media, can still fall short.

“Mainstream media in India is more impacted by the phenomena [of fake news] because they broadcast these kinds of stories without verifying,” says Prabhakar Kumar, from the Indian media research agency, CMS.

“There is no standard policy for TV news and newspapers about the process of researching and publishing stories.”

Police have arrested people accused of concocting false stories, especially when they run the risk of igniting communal tension. Administrators of Whatsapp groups have been warned they could be held responsible for the messages they oversee.

But social media has only enabled a much older reliance on rumour and innuendo, especially in India’s villages. Two boys in Dadri village, near Delhi, didn’t need Whatsapp last year to spread rumours a local man was storing beef in his freezer. They broadcast from the loudspeaker at the village temple. Mohammed Akhlaq, the 50-year-old labourer named by the boys, was lynched.

Michael Safi

By Kate Connolly, Angelique Chrisafis, Poppy McPherson, Stephanie Kirchgaessner, Benjamin Haas , Dominic Phillips, Elle Hunt and Michael Safi, The Guardian