Several Russian mass media, including Moskovskiy Komsomolets, have reported that Latvians plan to establish a special “ghetto” for Russians, though the basis for these stories is almost certainly a fake.

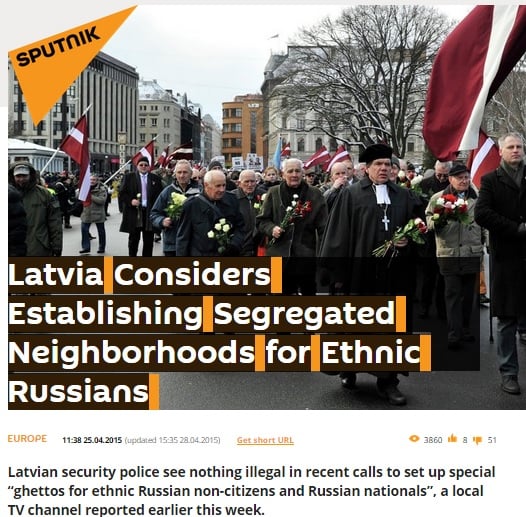

On April 25, the site of the Russian English-language news agency Sputniknews posted an article “Latvia Considers Establishing Segregated Neighborhoods for Ethnic Russians”.

These articles are based on a circulating petition entitled “To Stop the Russian Fifth Column in Our Motherland,” which is registered on the Latvian site peticijas.com by a certain Kaspars Mežavilks from Riga. As of April 28, the petition had been signed by almost 1,600 people.

The petition calls to support the Head of the Saeima, the Prime Minister, the Minister of Foreign Affairs, and the parliamentary secretary at the Latvian Justice Ministry in their struggle with the “Russian threat.” In addition to the efforts of the government, Mežavilks proposes to corral pro-Moscow activists (without citizenship, or with Russian citizenship and with residence permits) into areas controlled by police and security services.

“Only then Kremlin spies won’t be able to do harm to Latvia,” the petition claims. “We have to preserve the life force of our nation and wait for help from our NATO allies.”

This petition caused a stir in the mass media and among Latvian politicians. Jānis Iesalnieks, a parliamentary secretary at the Latvian Justice Ministry, via Twitter, called it a provocation and blamed the Kremlin for writing the “idiotic” petition about the Russian ghetto in Latvia.

https://twitter.com/JanisIesalnieks/status/592659019694796800

There are substantial reasons for considering the petition and the majority of signatures as a fakes, aimed at provoking a discussion about Latvia’s intolerance of Russians living there.

Stopfake consulted Latvian expert philologists. They state that many names of the people who signed the petition are “unrealistic” and “non-Latvian.” They give such names as Jūsmiņš Būmeisters, Brencis Lielībnieks, Bartolomejs Deģis, Dacis Ķēniņš, Adalberts Zemurbējs, Berils Barons, Vello Kirpļuks, Džordžs Vējš, Sirdsvaldis Stumburs, Renato Silamiķelis, Ironijs Lācis, Zviedrītis Gothards and so on.

Furthermore, there are doubts about how quickly the signatures were gathered. For example, on April 14, an unlikely number of people signed in the course of just one minute.

And during the first three days, more people signed than during the next twelve days. In the petition’s first day on line, April 14, signed. From April 21, an average of 60 signed a day, though from April 25, the number of signatures dramatically decreased to 10 per day.

Taking into consideration the broad media coverage in Latvia after the petition was launched and the corresponding downward trend in signatures (after the suspiciously strong opening), it is at least clear that it has little common support among the citizens of Latvia.