By Alexios Mantzarlis, Poynter

Evidence of Facebook’s fake news problem is piling up: The “Trending” section keeps getting hoaxed. Hyperpartisan pages spew fake posts that go viral. And traditional media are picking up those fakes as true.

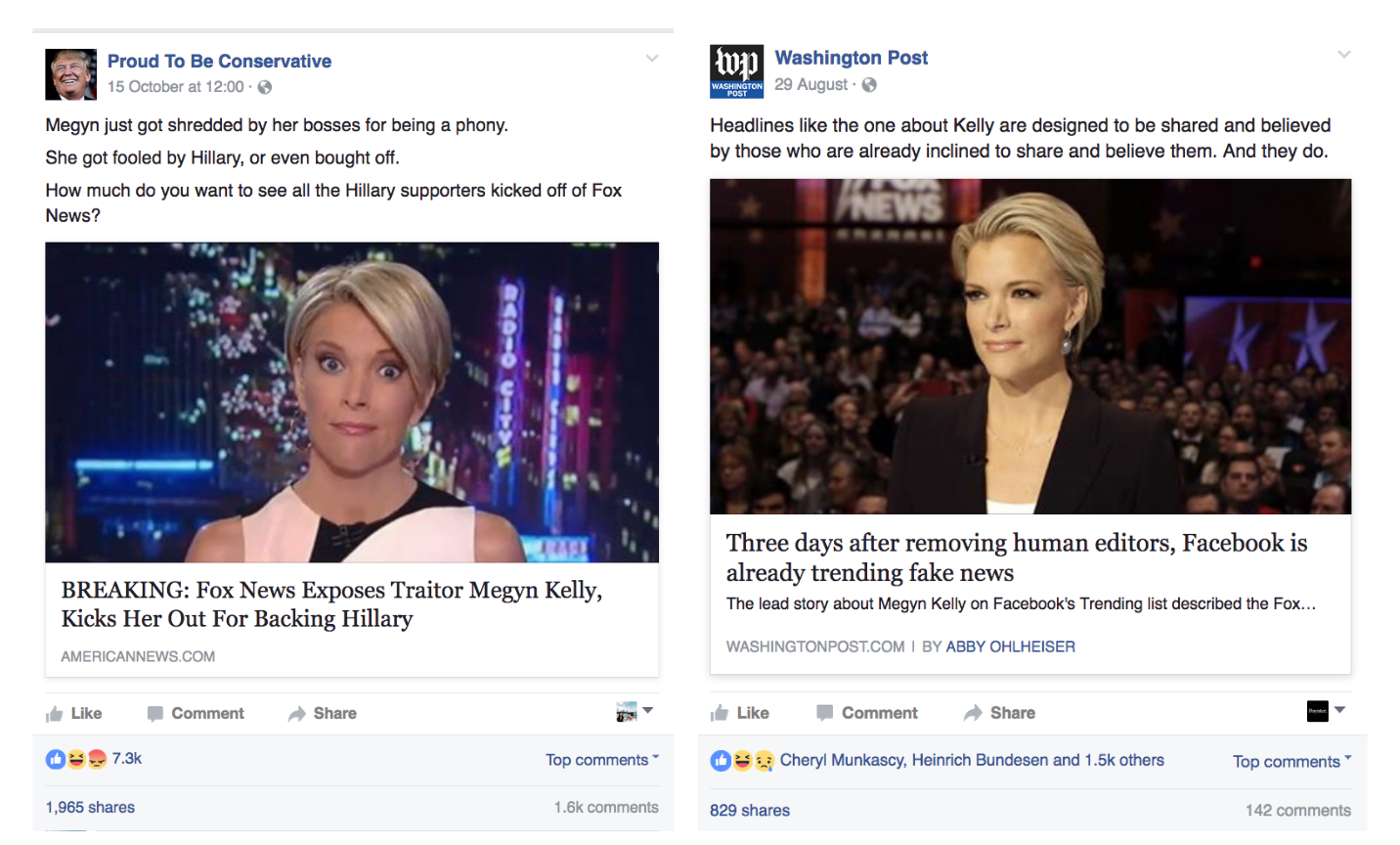

The bigger problem, however, is that Facebook seems incapable of rooting out hoaxes even after acknowledging they are clearly fake news. On Aug. 29, it apologized for putting Fox News host Megyn Kelly in “Trending” with a link to a bogus story headlined “Fox News Exposes Traitor Megyn Kelly, Kicks Her Out For Backing Hillary.”

The story was pulled from “Trending,” but its life on Facebook continued. On Sept. 10, the page “Conservative 101” posted a story with an almost identical headline (adding “BREAKING:” at the front). The post has 13,000 reactions and 2,700 shares.

A page called “American News” shared a similar story on Sept. 11, Sept, 29 and Oct. 3.

On Oct. 15, “Proud To Be Conservative” got in on the fun (7,300 reactions, 1,964 shares). It did so again last week (17,000 reactions and 4,387 shares).

At midnight on Thursday, a fifth page, “Proud Patriots” shared the same story (2,100 reactions, 571 shares).

To recap: at least five different pages shared a story after Facebook acknowledged it was fake and were still able to reach tens of thousands of people through the social network. None of the posts carry any warning that the content is fake. And the engagement was pretty good, if you consider that when The Washington Post shared the article that debunked the fake report it got 829 shares and 1,500 reactions.

Unlike when it was hit with allegations of bias — which led to the hasty elimination of a 15-person team and a meeting of conservative media leaders with Zuckerberg — Facebook hasn’t announced any substantive steps to combat bogus stories after they’ve left the “Trending” section.

The dramatic rise and extraordinary reach of “Fakebook”

The Megyn Kelly hoax is not an isolated incident. When The Washington Post’s Caitlin Dewey and Abby Ohlheiser tracked stories that were in “Trending” over the first three weeks of September, they found Facebook’s algorithm highlighted four other indisputably fake stories. These included an article claiming to prove that 9/11 was a conspiracy.

If this chicanery was confined to Facebook’s “Trending” section, it wouldn’t be so grave a matter. After all, who really relies on that service? The problem isn’t what is “Trending,” but what is literally trending. Fake stories appear in that top-right corner of Facebook because they are popular on our individual feeds.

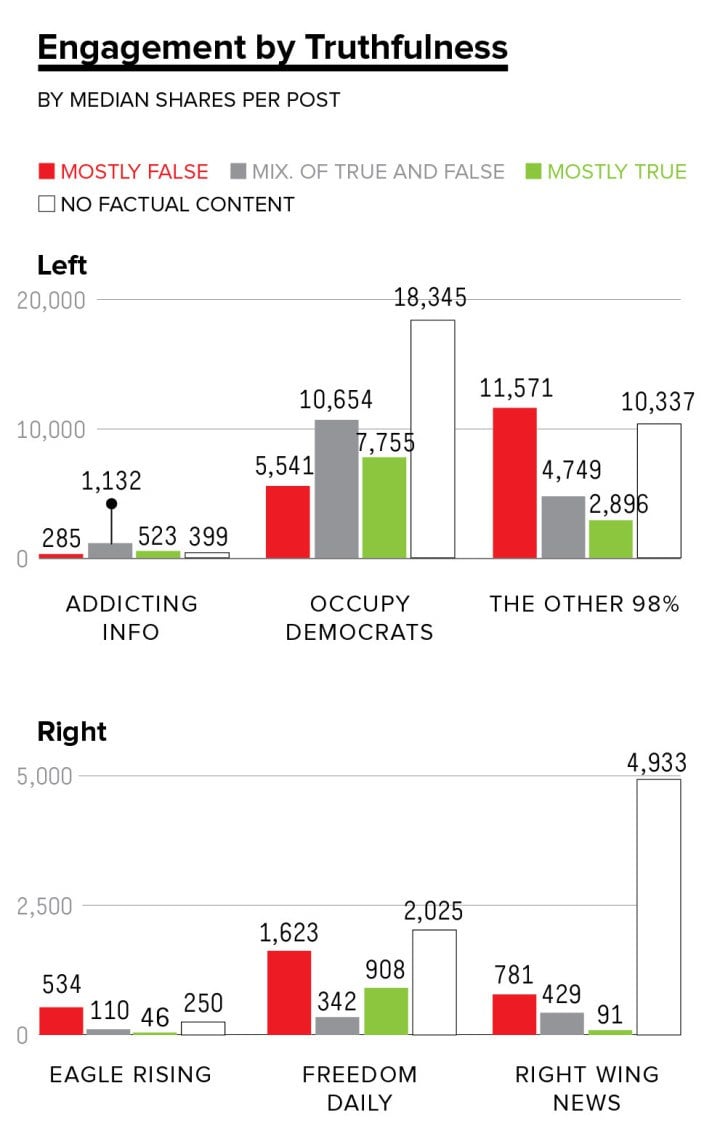

“Trending” is just the tip of a fake news iceberg: A BuzzFeed analysis of six hyperpartisan Facebook pages found that posts with mostly false content or no facts fared better than their truthful counterparts.

While recent studies have found that disinformation spreads faster and wider than related corrections on Twitter, previous work has found that to be true of Facebook, too.

Because reach means traffic, and traffic means ad revenue, Facebook is a key component of the business model of fake news sites.

And just as with fake news sites, the financial outlook for Facebook-native hyperpartisan pages appears rosy. In an analysis for The New York Times, John Herrman found that the administrator of one such page brings home “in a good month, more than $20,000.”

Blaming Facebook for human nature?

Facebook has defended itself by saying that hoaxes and the confirmation bias have long existed elsewhere. Cable news channels and tabloids were telling scantily-sourced stories long before Zuckerberg entered an “It’s Complicated” relationship with news media.

Looking back in history, “partisan media was one of the earliest types of media,” said BuzzFeed hoaxbuster Craig Silverman. And the “factors that made it successful are still true — people like to read stuff that confirms their beliefs.”

That’s how Zuckerberg sees it. Responding to a comment on his post about News Feed’s 10th anniversary, he wrote: “keep in mind that News Feed is already more diverse than most newspapers or TV stations a person might get information from.”

And yet, Facebook isn’t just another medium hoaxers can use to spread misinformation, or a new source of bias-confirming news for partisan readers. It turbocharges both these unsavory phenomena.

“Facebook is a game-changer,” Silverman said. “It’s a confirmation bias machine on a mass scale.”

Emily Bell, director at the Tow Center for Digital Journalism, agrees. Facebook is “designed to encourage repetitive consumption and interaction.” It is not “necessarily designed promote what is good information over what is bad information.”

Publishing before Facebook “was no shining city on the hill,” said Bell. Regardless, the expectations from a new media ecosystem is that it improves on the old. Instead, while “Facebook, Snapchat and Twitter are great at trumpeting how they have improved on the old systems,” they are “defensive and not very transparent on the areas where there are fair concerns.”

Fighting fakery more forcefully

Various arguments have been made as to why Facebook hasn’t cleaned up the fake news. The argument that vigorous intervention from Facebook to hamper fake news would somehow run afoul of the First Amendment (popular with some trolls) is bunk.

“Facebook has every legal right to engage in stronger fact-checking,” said Kevin M. Goldberg, an attorney and First Amendment specialist at Fletcher, Heald & Hildreth.

“As a private company [Facebook] cannot violate anyone’s First Amendment rights, given that the First Amendment only protects against unreasonable government regulation of speech and of the press. […] If I, as a private citizen who has chosen to join Facebook, don’t like that, I can shut down my account.”

Facebook insists that it doesn’t make editorial decisions with News Feed: It places the user first. If users say fakery is a problem, the company will act.

This argument is only partly convincing. The most recent hoax-fighting change to the News Feed algorithm was introduced in January 2015. At the time, the social network introduced the possibility for users to flag content as fake. It promised that stories flagged by enough people would be labeled and see reduced News Feed distribution. A company spokesperson had no comment for this article beyond pointing to the company’s 2015 post.

Almost two years later, it doesn’t look like the system for flagging fakes has met expectations — though without published data it is hard to tell for sure. Tom Trewinnard of Meedan, a nonprofit tech company, noted in June that the flagging process does not seem designed to encourage use: The number of clicks is high for Facebook, and the end result is “an unsatisfying array of options […] If you’re trying to make sure a fake story doesn’t get picked up by friends on the network, none of these options feels quite right.”

The flawed design indicates that Facebook “isn’t prioritizing the issue or that this isn’t the solution they’ve settled on,” Trewinnard told Poynter.

Therein lies one of two possible solutions. Encouraging and expanding the flagging process, perhaps by allowing users to provide more details and sources to explain what is wrong in the post, could strengthen the system.

Alternatively, Facebook could increase human oversight of hoaxes, starting from the ruins of the “Trending” process itself.

The “Trending” review team could be bolstered by a team of fact-checkers who would verify stories that are flagged as fake (this seems in line with their stated “quality assurance role”). Fake stories wouldn’t just be excluded from “Trending,” they would be flagged for News Feed users’ benefit. Variations of known fakes could also have an automatic label indicating the similarity with a previously flagged hoax.

In both cases, fake posts could see their reach handicapped and a page consistently distributing hoaxes banned. Sure, hoaxers could easily set new pages up. One fake news site owner made that case defiantly to BuzzFeed last year:

I could have 100 domains set up in a week, and are they going to stop every one of those? Are they now going to read content from every site and determine which ones are true and which ones are selling you a lie? I don’t see that happening. That’s not the way that the internet works.

But big followings — pages like the ones quoted at the top of the article have hundreds of thousands of likes — take time to build. A clear indication that this content will just not do as well as it has until now will eventually sap their enthusiasm.

These pages will exist as long as they make financial sense, but if Facebook — and Google for that matter — looked at sites completely made up of fake content and diluted their reach “it would shut them down,” Silverman said.

What will Facebook actually do

Zuckerberg’s comment about News Feed indicates that he is convinced the service is a better source of information than most traditional news outlets. Yet more variations of a Megyn Kelly hoax is no one’s idea of a good service.

“The best media outlets have always been concerned with how they present the news, hired public editors, instituted correction policies and other systems to filter and present the best information possible to their audience,” said Bell.

What will push Facebook into similar solutions? Bell said regulation and competition are two forces that have led to changes in errant media behavior in the past. Perhaps the social network will face similar challenges as Google did from the European Commission’s competition czar. “I think a lot of American analysts have been very skeptical about European attempts to regulate large technology platforms,” she said. “but those are actually the things that have moved the dial.”

With regulation and competition not seemingly on the horizon for the social network at this time, change will have to come either from the inside or from users.

Facebook has signed on to the First Draft Partner Network, an effort to stop the spread of fake news. It may also be egged on by the actions of other Silicon Valley giants: Google announced a relatively small change to its News service with lofty, aspirational language about the importance of accurate information:

We’re excited to see the growth of the Fact Check community and to shine a light on its efforts to divine fact from fiction, wisdom from spin.

User pressure is the other option. “If we get to the point that the user says ‘I don’t want to spend time on Facebook because there is so much misinformation’ — that’s the moment Facebook will act,” says Trewinnard. He thinks the company might also be compelled to act if growth starts lagging in emerging markets — there isn’t much space left to add users in the U.S. — because users seem reticent to sign up to a network flooded with fakes.

In the meantime, if you’ve reached this far down: Flag the latest viral fake on the 2008 election being rigged. If users really do come first, its reach should eventually get downgraded.

By Alexios Mantzarlis, Poynter