By Edward Lucas, for CEPA

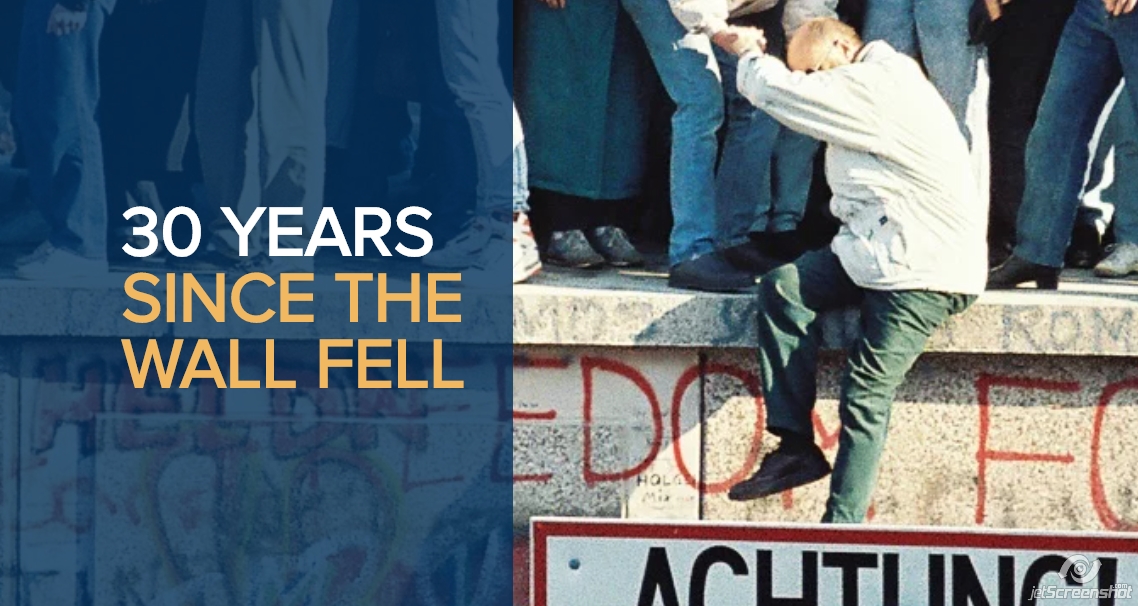

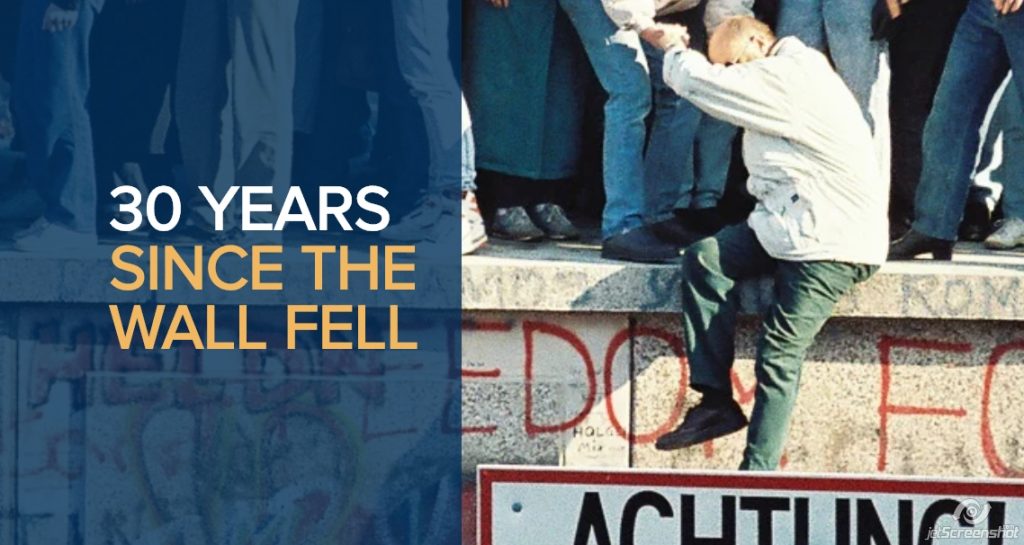

The division of Germany is fading into history. Don’t let its lessons fade as well.

I remember East Berlin. Even now, thirty years on, my throat constricts at the memory. Soft brown lignite smoldered in boiler furnaces, low-octane fuel burned in gimcrack cars and clapped-out trucks. The ideology was choking too. I would argue with leaden-tongued true believers at official functions and scour the stifling prose of Neues Deutschland, the newspaper of the ruling Socialist Unity Party, for clues about internal power struggles and shifts.

Terminology was ammunition. Both sides had difficulty in acknowledging the other’s existence. The authorities in the east put up road signs referring disparagingly to “Westberlin;” theirs was Berlin, with no adjectives. Hardcore cold warriors referred not to the self-styled German Democratic Republic but to the Sowjetische Besatzungszone —the Soviet-occupied zone of Germany. Between the eastern and western zones was one of the world’s most fortified frontiers, with self-firing guns, minefields, and other horrors. Berlin was lethally divided too. In February 1989 Chris Gueffroy, a 20-year-old waiter, was the last person shot trying to escape from the workers’ paradise. Escaping the other way was no risk at all. You just took a train and got off at Friedrichstrasse station.

As the BBC man in Berlin, I was technically a war correspondent, though the fighting had stopped more than forty years earlier. I had honorary military status, with rights (crossing at Checkpoint Charlie, with Pink Floyd’s The Wall blasting from my car), and obligations. If I crashed my car in the east, I was not to speak to the Vopos (the local police) but to demand the presence of a Soviet officer. I drove there, without crashing, every day, sometimes just to tease the border guards. They looked at me stonily, as if I were trying to smuggle my own nose. If my cheerful greetings cracked a smile, I reckoned, communism edged closer to collapse.

West Berlin was frozen in time too. Unlike in other countries, the Western allies who still ultimately ran the place resisted all pressure by the Soviet authorities to bring things up to date. I visited the decrepit Estonian embassy in Tiergarten, from which diplomats had departed in 1940. It was inhabited by a cheerful artist who was troubled by a recent visit from young Estonians. They had warned him that their occupied country would soon need its building back. It did. The Latvian embassy was long gone, but I interviewed a rather mistrustful lawyer who maintained the bank account. The site of the old Lithuanian embassy was a car dealership.

Also exotic, but less romantic, was the left-wingery. As West Berlin was not technically part of West Germany, young people living there could not be conscripted. The influx of draft dodgers fuelled a large “alternative” scene. Its denizens, lavishly subsidized by the taxpayer, railed against capitalism, imperialism, and the Western “occupiers,” oblivious to the presence of a real empire, just a few hundred yards away, that policed popular culture, persecuted hippies and anarchists, and sent those resisting military service to punishment brigades or mental hospitals.

The division of Berlin is fading into history, but its lessons are lasting. Ideology never went away. Studying Lenin’s works, especially on political warfare is useful. Parse turgid official pronouncements. They contain clues. Stay stubborn on terminology. The Baltic states were not granted independence in 1991—they regained it. Crimea is occupied. So is Tibet. Taiwan is a country, not a rebel province. Invisible walls remain. People seeking freedom do not flee to Communist China or (despite Edward Snowden’s defection) to Russia. They do come to the West, often at great risk. Anti-Westernism is self-indulgence: most people would love to have our problems.

By Edward Lucas, for CEPA

Europe’s Edge is an online journal covering crucial topics in the transatlantic policy debate. All opinions are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the position or views of the institutions they represent or the Center for European Policy Analysis.