The politically aware, digitally savvy and those more trusting of the news media fare better; Republicans and Democrats both influenced by political appeal of statements

By Amy Mitchell, Jeffrey Gottfried, Michael Barthel And Nami Sumida, for Pew Research Center

In today’s fast-paced and complex information environment, news consumers must make rapid-fire judgments about how to internalize news-related statements – statements that often come in snippets and through pathways that provide little context. A new Pew Research Center survey of 5,035 U.S. adults examines a basic step in that process: whether members of the public can recognize news as factual – something that’s capable of being proved or disproved by objective evidence – or as an opinion that reflects the beliefs and values of whoever expressed it.

In today’s fast-paced and complex information environment, news consumers must make rapid-fire judgments about how to internalize news-related statements – statements that often come in snippets and through pathways that provide little context. A new Pew Research Center survey of 5,035 U.S. adults examines a basic step in that process: whether members of the public can recognize news as factual – something that’s capable of being proved or disproved by objective evidence – or as an opinion that reflects the beliefs and values of whoever expressed it.

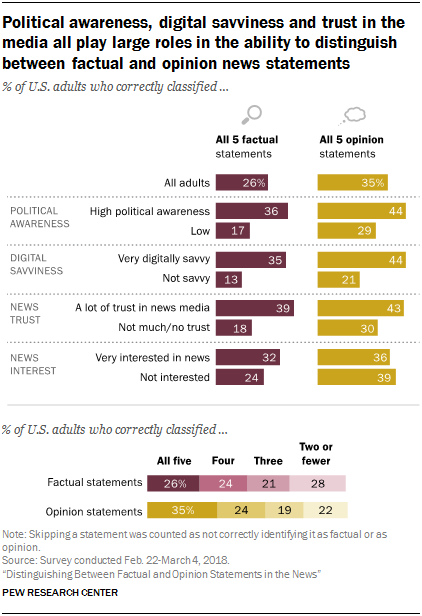

The findings from the survey, conducted between Feb. 22 and March 8, 2018, reveal that even this basic task presents a challenge. The main portion of the study, which measured the public’s ability to distinguish between five factual statements and five opinion statements, found that a majority of Americans correctly identified at least three of the five statements in each set. But this result is only a little better than random guesses. Far fewer Americans got all five correct, and roughly a quarter got most or all wrong. Even more revealing is that certain Americans do far better at parsing through this content than others. Those with high political awareness, those who are very digitally savvy and those who place high levels of trust in the news media are better able than others to accurately identify news-related statements as factual or opinion.

For example, 36% of Americans with high levels of political awareness (those who are knowledgeable about politics and regularly get political news) correctly identified all five factual news statements, compared with about half as many (17%) of those with low political awareness. Similarly, 44% of the very digitally savvy (those who are highly confident in using digital devices and regularly use the internet) identified all five opinion statements correctly versus 21% of those who are not as technologically savvy. And though political awareness and digital savviness are related to education in predictable ways, these relationships persist even when accounting for an individual’s education level.

Trust in those who do the reporting also matters in how that statement is interpreted. Almost four-in-ten Americans who have a lot of trust in the information from national news organizations (39%) correctly identified all five factual statements, compared with 18% of those who have not much or no trust. However, one other trait related to news habits – the public’s level of interest in news – does not show much difference.

In addition to political awareness, party identification plays a role in how Americans differentiate between factual and opinion news statements. Both Republicans and Democrats show a propensity to be influenced by which side of the aisle a statement appeals to most. For example, members of each political party were more likely to label both factual and opinion statements as factual when they appealed more to their political side.

At this point, then, the U.S. is not completely detached from what is factual and what is not. But with the vast majority of Americans getting at least some news online, gaps across population groups in the ability to sort news correctly raise caution. Amid the massive array of content that flows through the digital space hourly, the brief dips into and out of news and the country’s heightened political divisiveness, the ability and motivation to quickly sort news correctly is all the more critical.

The differentiation between factual and opinion statements used in this study – the capacity to be proved or disproved by objective evidence – is commonly used by others as well, but may vary somewhat from how “facts” are sometimes discussed in debates – as statements that are true.1 While Americans’ sense of what is true and false is important, this study was not intended as a knowledge quiz of news content. Instead, this study was intended to explore whether the public sees distinctions between news that is based upon objective evidence and news that is not.

To accomplish this, respondents were shown a series of news-related statements in the main portion of the study: five factual statements, five opinions and two statements that don’t fit clearly into either the factual or opinion buckets – termed here as “borderline” statements. Respondents were asked to determine if each was a factual statement (whether accurate or not) or an opinion statement (whether agreed with or not). For more information on how statements were selected for the study, see below.

How the study asked Americans to classify factual versus opinion-based news statements

In the survey, respondents read a series of news statements and were asked to put each statement in one of two categories:

A factual statement, regardless of whether it was accurate or inaccurate. In other words, they were to choose this classification if they thought that the statement could be proved or disproved based on objective evidence.

A factual statement, regardless of whether it was accurate or inaccurate. In other words, they were to choose this classification if they thought that the statement could be proved or disproved based on objective evidence.- An opinion statement, regardless of whether they agreed with the statement or not. In other words, they were to choose this classification if they thought that it was based on the values and beliefs of the journalist or the source making the statement, and could not definitively be proved or disproved based on objective evidence.

In the initial set, five statements were factual, five were opinion and two were in an ambiguous space between factual and opinion – referred to here as “borderline” statements. (All of the factual statements were accurate.) The statements were written and classified in consultation with experts both inside and outside Pew Research Center. The goal was to include an equal number of statements that would more likely appeal to the political right or to the political left, with an overall balance across statements. All of the statements related to policy issues and current events. The individual statements are listed in an expandable box at the end of this section, and the complete methodology, including further information on statement selection, classification, and political appeal, can be found here.

Republicans and Democrats are more likely to think news statements are factual when they appeal to their side – even if they are opinions

It’s important to explore what role political identification plays in how Americans decipher factual news statements from opinion news statements. To analyze this, the study aimed to include an equal number of statements that played to the sensitivities of each side, maintaining an overall ideological balance across statements.2

Overall, Republicans and Democrats were more likely to classify both factual and opinion statements as factual when they appealed most to their side. Consider, for example, the factual statement “President Barack Obama was born in the United States” – one that may be perceived as more congenial to the political left and less so to the political right. Nearly nine-in-ten Democrats (89%) correctly identified it as a factual statement, compared with 63% of Republicans. On the other hand, almost four-in-ten Democrats (37%) incorrectlyclassified the left-appealing opinion statement “Increasing the federal minimum wage to $15 an hour is essential for the health of the U.S. economy” as factual, compared with about half as many Republicans (17%).3

News brand labels in this study had a modest impact on separating factual statements from opinion

In a separate part of the study, respondents were shown eight different statements. But this time, most saw statements attributed to one of three specific news outlets: one with a left-leaning audience (The New York Times), one with a right-leaning audience (Fox News Channel) and one with a more mixed audience (USA Today).4

In a separate part of the study, respondents were shown eight different statements. But this time, most saw statements attributed to one of three specific news outlets: one with a left-leaning audience (The New York Times), one with a right-leaning audience (Fox News Channel) and one with a more mixed audience (USA Today).4

Overall, attributing the statements to news outlets had a limited impact on statement classification, except for one case: Republicans were modestly more likely than Democrats to accurately classify the three factual statements in this second set when they were attributed to Fox News – and correspondingly, Democrats were modestly less likely than Republicans to do so. Republicans correctly classified them 77% of the time when attributed to Fox News, 8 percentage points higher than Democrats, who did so 69% of the time.5 Members of the two parties were as likely as each other to correctly classify the factual statements when no source was attributed or when USA Today or The New York Times was attributed. Labeling statements with a news outlet had no impact on how Republicans or Democrats classified the opinion statements. And, overall, the same general findings about differences based on political awareness, digital savviness and trust also held true for this second set of statements.

When Americans call a statement factual they overwhelmingly also think it is accurate; they tend to disagree with factual statements they incorrectly label as opinions

The study probed one step further for the initial set of 12 statements. If respondents identified a statement as factual, they were then asked if they thought it was accurate or inaccurate. If they identified a statement to be an opinion, they were asked whether they agreed or disagreed with it.

When Americans see a news statement as factual, they overwhelmingly also believe it to be accurate. This is true for both statements they correctly and incorrectly identified as factual, though small portions of the public did call statements both factual and inaccurate.

When Americans incorrectly classified factual statements as opinions, they most often disagreed with the statement. When correctly classifying opinions as such, however, Americans expressed more of a mix of agreeing and disagreeing with the statement.

About the study

Statement selection

This is Pew Research Center’s first step in understanding how people parse through information as factual or opinion. Creating the mix of statements was a multistep and rigorous process that incorporated a wide variety of viewpoints. First, researchers sifted through a number of different sources to create an initial pool of statements. The factual statements were drawn from sources including news organizations, government agencies, research organizations and fact-checking entities, and were verified by the research team as accurate. The opinion statements were adapted largely from public opinion survey questions. A final list of statements was created in consultation with Pew Research Center subject matter experts and an external board of advisers.

The goals were to:

- Pull together statements that range across a variety of policy areas and current events

- Strive for statements that were clearly factual and clearly opinion in nature (as well as some that combined both factual and opinion elements, referred to here as “borderline”)

- Include an equal number of statements that appealed to the right and left, maintaining an overall ideological balance

In the primary set of statements, respondents saw five factual, five opinion and two borderline statements. Factual statements that lend support to views held by more people on one side of the ideological spectrum (and fewer of those on the other side) were classified as appealing to the narrative of that side. Opinion statements were classified as appealing to one side if in recent surveys they were supported more by one political party than the other. Two of the statements (one factual and one opinion) were “neutral” and intended to appeal equally to the left and right.

How Pew Research Center asked respondents to categorize news statements as factual or opinion

As noted previously, respondents were first asked to classify each news statement as a factual statement or an opinion statement. Extensive testing of the question wording was conducted to ensure that respondents would not treat this task as asking if they agree with the statement or as a knowledge quiz. This is why, for instance, the question does not merely ask whether the statement is a factual or an opinion statement and instead includes explanatory language as follows: “Regardless of how knowledgeable you are about the topic, would you consider this statement to be a factual statement (whether you think it is accurate or not) OR an opinion statement (whether you agree with it or not)?” For more details on the testing of different question wordings, see Appendix A.

After classifying each statement as factual or opinion, respondents were then asked one of two follow-up questions. If they classified a statement as factual, they were then asked if they thought the statement was accurate or inaccurate. If they classified it as an opinion, they were asked if they agreed or disagreed with the statement.

- For example, fact-checking organizations have used this differentiation of a statement’s capacity to be proved or disproved as a way to determine whether a claim can be fact-checked and schools have used this approach to teach students to differentiate facts from opinions. ↩

- A statement was considered to appeal to the left or the right based on whether it lent support to political views held by more on one side of the ideological spectrum than the other. Various sources were used to determine the appeal of each statement, including news stories, statements by elected officials, and recent polling. ↩

- The findings in this study do not necessarily imply that one party is better able to correctly classify news statements as factual or opinion-based. Even though there were some differences between the parties (for instance, 78% of Democrats compared with 68% of Republicans who correctly classified at least three of five factual statements), the more meaningful finding is the tendency among both to be influenced by the possible political appeal of statements. ↩

- The classification of these three outlets’ audiences is based on previously reported survey data, the same data that was used to classify audiences for a recent study about coverage of the Trump administration. For more detail on the classification of the three news outlets, as well as the selection and analysis of this second set of statements, see the Methodology. At the end of the survey, respondents who saw news statements attributed to the news outlets were told, “Please note that the statements that you were shown in this survey were part of an experiment and did not actually appear in news articles of the news organizations.” ↩

- This analysis grouped together all of the times the 5,035 respondents saw a statement attributed to each of the outlets or no outlet at all. The results, then, are given as the “percent of the time” that respondents classified statements a given way when attributed to each outlet. For more details on what “percent of the time” means, see the Methodology.

By Amy Mitchell, Jeffrey Gottfried, Michael Barthel And Nami Sumida, for Pew Research Center