Disinformation related to the UN Charter, signed on 26 June 1945, appears frequently in pro-Kremlin disinformation outlets. Most of the over 140 cases on this topic the EUvsDisinfo database on disinformation are false claims, suggesting the illegal annexation of Crimea was in line with the UN Charter. It was not. It was a blatant violation of both the spirit and the letter of the Charter.

Other false claims concern “UN bias” and the UN as a “channel for Russophobia”.

Still, the UN Charter is frequently evoked by Russian foreign policy officials:

The core tenets of international law enshrined in the UN Charter have withstood the test of time.

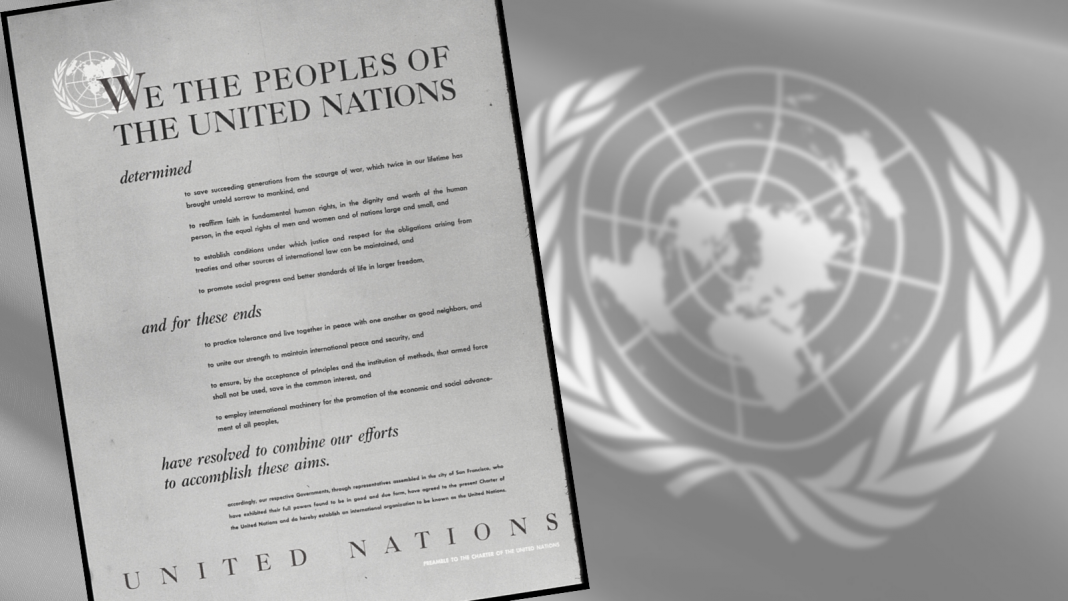

The UN Charter is certainly a cornerstone of international law, a foundation of the rules-based international order. It was signed during the last months of World War II – Japan capitulated only in September 1945 – and it focuses on the experience of the peoples:

WE THE PEOPLES OF THE UNITED NATIONS DETERMINED to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war, which twice in our lifetime has brought untold sorrow to mankind, and to reaffirm faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person, in the equal rights of men and women and of nations large and small.

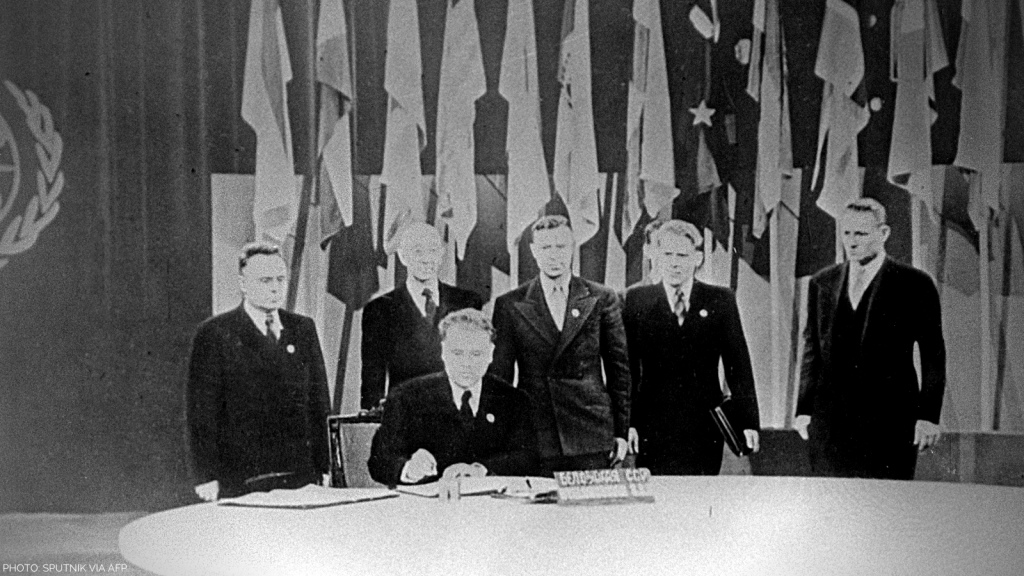

The Soviet Union and the Soviet republics of Belarus and Ukraine were among the 51 original signatories. Russia, at the time one of the 16[1] Soviet Republics, was not represented.

Kuzma Kizyalyou, Head of the Belorusian delegation, signing the UN charter 1945.

The Spoils of Victory

Already from the beginning, the Kremlin used the UN as an instrument for imperialistic ambitions, instead of subjecting itself to the principles of universal human rights. The Soviet Union was the only permanent member of the UN Security Council that made substantial territorial gains from World War II. Russia continues to refer to the UN Charter to justify its foreign policy ambitions.

Today, Russian foreign ministry officials combine the utterance of the words “UN Charter” and “non-intervention in internal affairs” in the same sentence. The quote above continues:

Russia calls on all states to unconditionally follow the purposes and principles of the Charter as they chart their foreign policies, respecting the sovereign equality of states, not interfering in their internal affairs, settling disputes by political and diplomatic means, and renouncing the threat or use of force.

Another example is here:

Firm commitment to the purposes and principles of the UN Charter, including the sovereign equality of states, non-intervention in internal affairs and the refraining from the threat or use of force.

Or here:

Representatives of the EU and its member countries repeatedly mention lack of geopolitics in their positions. However, the EU’s decisions, its language of threats and other actions regarding Belarus point to the contrary. They are obviously violating one of the key principles of the UN Charter and the OSCE Helsinki Final Act – non-interference in internal affairs.

One might get the impression that non-interference in internal affairs is actually a key principle of the UN Charter, but the closest we get is Article 4:

All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state.

The term “human rights” is, on the other hand, mentioned seven times in the Charter.

Universal Rights

The UN Charter is rooted in a process where the ideas of equality, human rights and dignity were posited as universal rights not subject to the whims of a sovereign. Ideas of universal human rights inspired the “Founding Fathers” of the US and the Declaration of Independence, the French Revolution, the 1791 Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth’s Constitution. The ideas inspired the Russian Decembrists, a group of military officers who outlined a Russian constitution, similar to the US one, and rebelled against the Tsar in 1825.

The idea that human rights could be larger than the sovereign’s rights took root slowly in international affairs. This is reflected in a process of conventions, describing a transnational legal system, primarily connected to warfare: the 1856 Paris Declaration, the 1899 and 1907 Hague Conventions, the 1864, 1928 and 1949 Geneva Conventions.

This process was crowned by the UN Charter in 1945. The referent object of international security was no longer the state, but the people.

Other international organisations are based on the same principle: the person, the individual is the referent object of security. Neither kings, nor sovereigns, princes or presidents. This is the core principle of the Helsinki Final Act of 1975 and the OSCE; this is the fundamental idea of the European Union.

Russia insists on using the UN and the OSCE as a smorgasbord, carefully selecting what is useful for its foreign policy ambitions.