The advantage of the lie

Why do lies have an impact in the public space? One answer is that it’s because truth is often unclear, unstable. People prefer stories that remove their uncertainty. When COVID-19 struck the world a year ago, some really wanted to believe this was just a type of flu. Maybe a bit stronger, but nothing to worry about. Disinformation actors exploited this. In the same period, other narratives did acknowledge the dangers, but subsequently explained them in terms of already existing beliefs; like the threat of global elites, evil billionaires, or China.

Hannah Arendt explained this phenomenon in her 1971 essay Lying in Politics:

“It is this fragility that makes deception so very easy up to a point, and so tempting. It never comes into a conflict with reason, because things could indeed have been as the liar maintains they were. Lies are often much more plausible, more appealing to reason, than reality, since the liar has the great advantage of knowing beforehand what the audience wishes or expects to hear. He has prepared his story for public consumption with a careful eye to making it credible, whereas reality has the disconcerting habit of confronting us with the unexpected, for which we were not prepared.”

Wired to jump to conclusions

Arendt explains why liars have a great advantage. But, also in the seventies, two outstanding psychologists, Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, contributed to a better understanding why we are prone to fall for these easy truths. They showed that we, human beings, are wired to jump to conclusions. Moreover, why we make many mistakes along the way.

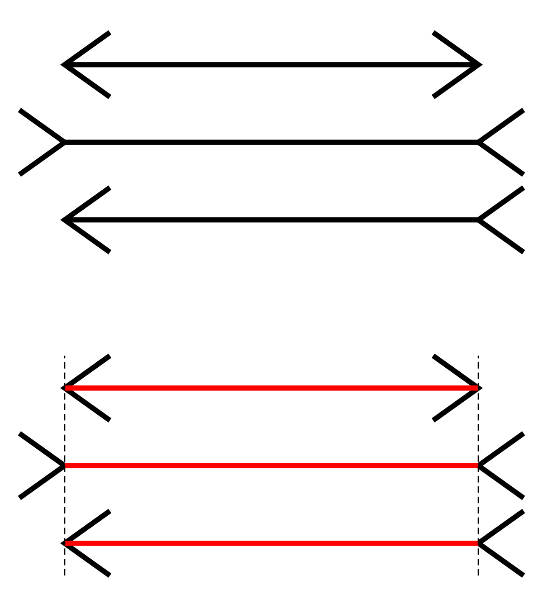

Look, for example, at the picture below. It causes us to believe these lines are of different sizes.

Source: Müller-Lyer illusion

Kahneman and Tversky called these mental processes “heuristics”; mental shortcuts to draw a conclusion. These shortcuts are innate in us and occur automatically, without us knowing. Consequently, we make mistakes and we are not aware we make them.

For the representativeness heuristic, the researchers showed how people ignore base rates, or likely outcomes, and are biased by a narrative or a story when it is representative of a different outcome. They also established, which many studies have confirmed, that people neglect prior probabilities in favor of a representative description provided. This ‘framing’ of developments into representative stories the audience already knows is exactly what disinformation often does. For example, last week we noticed that all the disinformation narratives we looked at – from Ukraine to COVID-19 vaccines – had one feature in common: the idea the West plans to establish a world order.

Filter bubbles: confirmation bias on steroids

One important mental shortcut is confirmation bias: the tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information in a way that confirms one’s prior beliefs or values. In 2019, we wrote about how confirmation bias can help making disinformation credible.

If confirmation bias is an innate problem of humans, imagine the influence filter bubbles have here. Research confirms this: confirmation bias is amplified by the use of filter bubbles, or “algorithmic editing”, which displays to individuals only information they are likely to agree with, while excluding opposing views. People forget the value of being contradicted.

We live in a messy world

The price of knowledge is uncertainty. Although our brain craves for confirmation, science is a process of crossing out false theses. In a way, this is also true for democracy and journalism. All three contribute to humankind’s well-being; but they also create a degree of uncertainty, as they are platforms for competition for truth and power. In contrast with lying, as Arendt described, they are open-ended, they produce outcomes that are not fixed beforehand. This uncertainty is exploited by disinformation. At the same time, these platforms are denigrated by disinformation relentlessly, as the drivers of disinformation fear nothing as non-closure. This explains why our database contains 436 cases on George Soros. As a former student of Karl Popper, the philosopher of falsification, and a loud defender of the open democratic societies, he is an ideological enemy.

The narrative that counters openness: eternity

The pro-Kremlin media have their counter-narrative against openness: eternity. Narrators of eternity perceive no progress but unending cycles of death and rebirth repeating themselves. Timothy Snyder, a historian, showed that the Kremlin has adopted an eternity narrative. Eternity can come in handy. Take the tensions in Ukraine. According to pro-Kremlin media, Crimea is a part of eternal Russia. In the same fashion, Donbas, by its nature, is Russian.

The eternity narrative, as we showed before, necessitates intolerance of those disagreeing. By questioning the narrative’s supposed truth, one removes himself from the community of faithful. This helps understanding how pro-Kremlin media operate. Conceptually, they work as “tribune”. Its characteristics are top-down communication, loyalty to hierarchy and just two types of expression: praise or condemnation. An opposition politician, Navalny, becomes a Western spy. Protests against the government, are set up by foreign actors. If investigative journalists, for example, those of Bellingcat, come up with uncomfortable results in an investigation, you do not focus on the research itself, instead, you attack the collective, portraying it as a factory of fake.

The brain craves confirmation; the stories of eternity are appealing; the search for the truth, however, is messy, and hard work. So, beware of comfort. In the words of Vaclav Havel:

“Keep the company of those who seek the truth― run from those who have found it”.