By Amanda Lichtenstein, for Global Voices

Disinformation — intentionally “fake news” — is a chronic problem everywhere in the world, but the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated information overload. From fake coronavirus cures to misleading information about mandatory vaccinations that have stoked fears worldwide, it has become increasingly difficult to suss out the truth.

All it takes is the click of a “share” or “forward” button for disinformation to become misinformation that spreads like wildfire through personal networks on applications and platforms like WhatsApp and Facebook.

Across Africa, where internet penetration is still relatively low at about 40 percent on average, many users are coming online for the first time. And around the world, many internet users, whether experienced or not, lack the digital literacy tools necessary to distinguish trustworthy news from false news.

How can all internet users become more discerning online?

This is the main idea behind “Choose Your Own Fake News,” a web-based game exploring how disinformation spreads across East Africa, created by Neema Iyer, founder and director of Pollicy, an Uganda-based organization supporting civic technology across the continent.

Iyer explained the motivation behind her game in a Mozilla Foundation press release:

Online misinformation has real implications offline. It can threaten people’s lives, freedom of expression, and prosperity. This is especially true in parts of East Africa, where people are coming online for the first time and don’t yet have the proper context to distinguish what’s trustworthy from what’s not.

‘Did you see that video on WhatsApp?’

“Chose Your Own Fake News” teaches new internet users how to be more discerning about the information they receive and encounter in digital spaces.

Players select one of three characters in East Africa: Flora, a job-seeking student, Jo, a shopkeeper, or Aida, a 62-year-old retired grandmother. Players then scrutinize news headlines, videos and social media posts through the lens of each character.

Flora, a job-seeking student, Jo, a shopkeeper, and Aida, a retired grandmother, are characters in the game “Choose Your Own Fake News” that must make decisions about what to do when they encounter potentially false information online, Screenshot from the game produced by Pollicy.

“Players’ decisions make the difference between correctly debunking disinformation — or falling victim to fraud, hospitalizing a loved one, and even accidentally inciting a mob,” the Mozilla press release explained.

As players follow their character’s various decisions, the game provides detailed information about how dis- and misinformation work, highlighting the role that individuals play in intercepting false or unverified information before they spread it.

For example, Aida receives a forwarded message from her cousin with a video of a child crying after receiving a measles vaccine. Should Aida share that video? Measles is vaccine-preventable but cases continue to soar due to false information.

“Platforms like YouTube and Facebook recommend and amplify content that keeps internet users clicking — even if it’s radical or flat-out wrong,” Mozilla Foundation said.

Forward-forward-forward-stop

Neema Iyer created “Choose Your Own Fake News,” and is the founder of Pollicy in Uganda. Photo used with permission.

In Season 2, Episode 3 of “Terms and Conditions,” a new podcast exploring digital rights in Africa, Neema Iyer speaks with digital rights activist Berhane Taye, to look at the history of online disinformation in Africa and how it intersects with bots, trolls and beyond.

Iyer and Taye talk about the potentially dangerous consequences of a seemingly simple forward or share.

The internet is riddled with bots — a software application that runs automated tasks. Iyer estimates that up to half of all online activity is run by bots designed to influence and shape opinions online. Trolls — real-life people — also disrupt, attack and offend with intention. Deepfakes — radically altered videos — can often make fiction seem real.

This mixture of online agitators contributes to disinformation that ultimately causes chaos, discord and polarizes communities, said Iyer.

To complicate matters, many internet users are “unwitting agents” who amplify false information without realizing it, writes Kate Starbird in Nature.

Mobile phones and SMS text messaging have long been used as tools for organizing mob justice and destabilizing communities, but it wasn’t until WhatsApp and other platforms emerged that false information could spread so rapidly and exponentially with the click of a button, Iyer continued.

Iyer cites the lynchings in India caused by WhatsApp rumors about child kidnappings and the sectarian violence in Nigeria that erupted after images circulated on WhatsApp showed accused Fulani Muslim people committing acts of violence against Christians.

In April 2020, at the height of the pandemic, WhatsApp finally took action to curb the spread of fake news by limiting the number of forwards from five to one. “The move is designed to reduce the speed with which information moves through WhatsApp, putting truth and fiction on a more even footing,” according to The Verge.

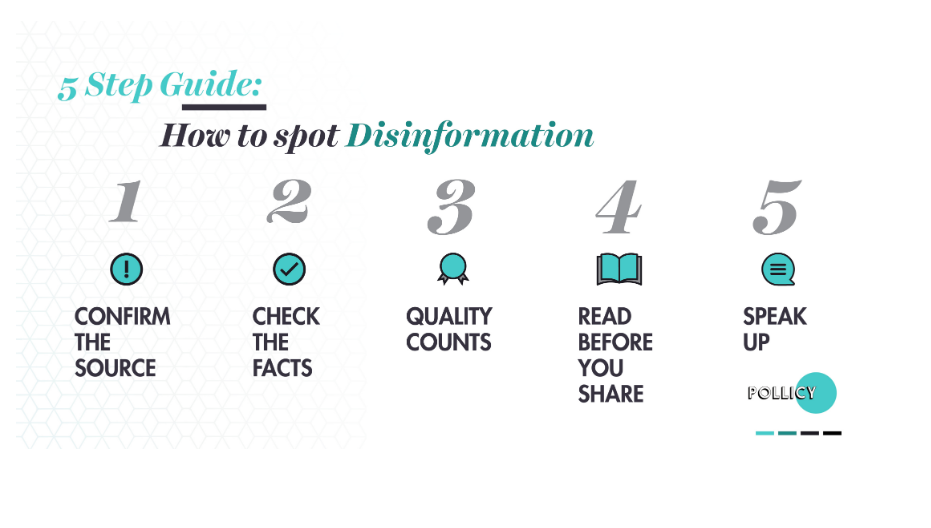

How to spot disinformation: A screenshot from “Choose Your Own Fake News,” an online game designed by Pollicy in Uganda.

To criminalize or not to criminalize?

People often turn to social media to fill gaps left by mainstream media. But with the democratization of social media, anyone can produce content — with very few guidelines for monitoring, vetting, or fact-checking.

In East Africa, governments have created a range of policies and laws designed to control “fake news” and hate speech — but they end up becoming the rationale for penalizing opposition or dissenting voices.

In March 2020, in South Africa, the government criminalized the sharing of COVID-19 information “intended to deceive citizens or the government’s response to the pandemic” under the 2002 Disaster Management Act — violators may receive fines, imprisonment, or both, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ).

CPJ warned, however, that “passing laws that emphasize criminalizing disinformation over educating the public and encouraging fact-checking present a slippery slope.”

In Nigeria, disinformation has sown distrust in institutions that “should ideally be the lighthouse during a pandemic” said ‘Gbenga Sesan, executive director of the Paradigm Initiative in Nigeria, who joined Iyer and Taye on “Terms and Conditions.”

“You have a lot of information that should not get into the hands of vulnerable people,” Sesan, referring to the deluge of videos, messages and memes shared to promote fake coronavirus cures.

But Nigeria’s Protection from Internet Falsehood and Manipulation Bill — known as the “social media bill” — is woefully inadequate and dangerously vague to truly make a dent in the problem.

Making the truth go viral

Research shows that it is very difficult to change a person’s mind once an idea gets planted and let’s face it — the typical internet user often glances headlines.

AI technology can attempt to intercept fake news or hate speech but this method is often inaccurate and does not capture nuance in terms of language and cultural context, Iyer explained.

For example, Facebook’s 2020 Transparency report claimed to remove 9.6 million pieces of content that were hateful or deemed hateful in the first four months of 2020, Iyer said. But she cautioned the likelihood of false positives.

Content moderators have immense power to take down anything deemed false or hateful, but Facebook does not hire adequately to handle multiple languages and cultural contexts. Also, many users are unaware of their power to report content.

Fact-checkers also do not have the reach to sway opinion once fake news takes hold — in the United States alone, they are outspent by campaigns 100 to one. Fact-checking also varies greatly depending on a country’s laws regarding transparency, data and freedom of information. In Tanzania, for example, the government has essentially prohibited fact-checking, insisting that its statistics are the absolute truth.

How do we discourage the spread of misinformation? Iyer insists on disrupting fake news before you spread it. Instead, make the truth go viral.

By Amanda Lichtenstein, for Global Voices