By Mitzi Perdue, for CEPA

Disappointed by the government’s lack of action, a former US Senator has taken up the information struggle through a YouTube channel for ordinary Russians.

What is the world’s most effective weapon?

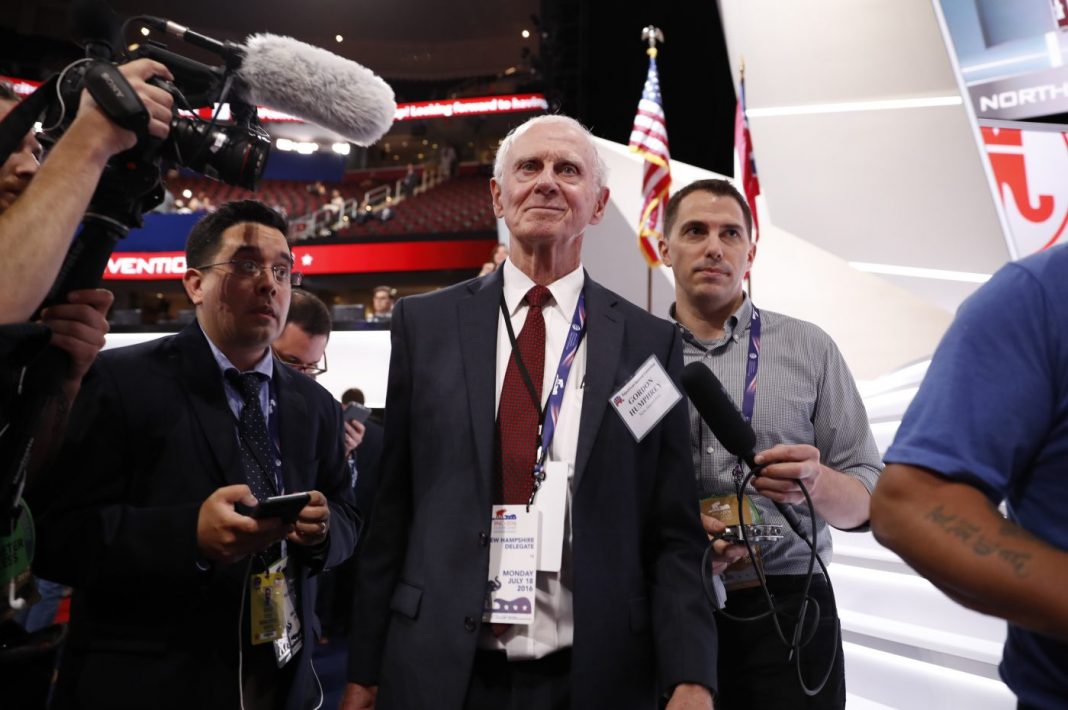

Retired New Hampshire Senator Gordon Humphrey (1978-90), who served on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, has an answer: Information warfare, the kind the Russians have been deploying unopposed against the United States for the last 25 or more years.

As Humphrey sees it, information warfare is not only the Kremlin’s most effective weapon for obtaining its strategic goals, it is also its greatest bargain. Compared to the cost of conventional weaponry, information warfare is almost free. And it’s far more useful than nuclear weapons because there’s no danger of retaliation. Most of all, it’s unrivaled in weakening adversaries and getting them to act against their interests.

Does anyone have an answer for how to oppose this? Yes, says Humphrey, a former Republican. He argues that the US prevailed in the Cold War in large measure by persuading Soviet citizens that “life on our side of the Iron Curtain was better than on theirs.”

Humphrey highlights the role played by the US Information Agency in the Soviet Union’s collapse. Broadcasting on shortwave radio, its Voice of America and Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, attracted large audiences with programs about American culture, including a highly popular series on jazz.

But the key was RFE’s most popular Russian-language program during the 1980s, featuring interviews with Soviet immigrants to the US. RFE reporters interviewed them in their homes and at work, play, and study. It was a window on America that offered a dramatically different view than the one depicted by Soviet propaganda — the information war of its day.

After the Cold War ended, American efforts to tell its story to the world sharply diminished. In 1999, Congress abolished USIA, concluding that freedom had won a permanent victory. Ever since, according to Humphrey, the US has lacked “the vision, commitment, leadership, organization, assembled talent and budget to prevail in the war of ideas.”

As a consequence, he says: “The country that invented the internet, is losing the information war by default . . . One need only visit government social media sites to see how perfunctory they are, how boring their content is, and how few foreign visitors and subscribers they attract.”

Humphrey, now 83, recently launched an updated version of RFE’s Russian-targeted program. He established a nonprofit and assembled a small team to create a Russian-language YouTube channel that posts interviews with recent Russian immigrants legally residing in the US.

“We’re already millionaires!” Humphrey says with delight, referring to the fact that the videos have been viewed more than a million times since the first was posted three months ago. Viewer comments and YouTube analytics indicate most of the viewers are in Russia. (While YouTube was recently banned by the Putin regime, it remains accessible to those with a virtual private network, or VPN.)

For Humphrey, the fascination with Russia all started in the tiny kitchen of a Moscow flat after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. While visiting the newly independent Russia, he stayed in a typical Soviet apartment. There was a knock at the door. Neighbors insisted he come over.

“They brought every treat they had in the refrigerator and cupboard. It’s an old Russian tradition, almost sacred in observance. That’s the real Russia, not the Russia of Putin,” Humphrey says. “That’s the Russia we need to encourage today by reaching out to ordinary Russians, as we reached out to Soviet citizens not so long ago. It’s the human thing to do, it’s the smart thing to do from the standpoint of national security.”

So what’s the goal?

“We’re tiny,” Humphrey says of the YouTube channel, “but imagine the reach and effect if the US government would again mount a serious effort of this kind.

The videos are non-confrontational. The name of Vladimir Putin never comes up. Instead, the interviewees are encouraged to talk about their experiences in the US, how they’ve been treated, how they’re getting along financially, what they like and dislike about America

“It’s down-to-earth stuff,’ Humphrey says, “Russians telling their relatives and friends back home what the real America is like, as distinct from the America that Kremlin propaganda portrays every day.”

What do the recent immigrants dislike about America? Mostly the food, which is too sweet or too salty and pre-packaged, unlike the home-cooked meals most Russians savor. What else? The high cost of medical care. What else? Very little.

What do they like about America? The friendliness, helpfulness and hospitality. Many report being invited over by neighbors soon after arriving. More broadly, Humphrey reports the interviewees frequently comment on the economic opportunity. Some call it strana vozmozhnoste — the land of opportunity.

Comments left by Russian viewers often express disbelief and some accuse the interviewees of lying or being traitors. “We take such comments as evidence we’re reaching our target audience,” Humphrey says. “Russians who’ve been misled by their government. That the views of our videos are growing rapidly in number means we’re also reaching what might be called a ‘silent majority,’ those who don’t leave comments but keep coming back for more.”

Humphrey’s ambitious plans require greater financial resources than he and a few friends currently offer. To that end, his team has created a second YouTube channel where Americans, with the help of English-language voiceover, can view the same videos Russian citizens are watching.

Humphrey hopes that the channel will spread the word and that financial support for his nonprofit will be forthcoming from foundations.

By Mitzi Perdue, for CEPA

Mitzi Perdue is a journalist reporting from and about Ukraine.

Europe’s Edge is CEPA’s online journal covering critical topics on the foreign policy docket across Europe and North America. All opinions are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the position or views of the institutions they represent or the Center for European Policy Analysis.