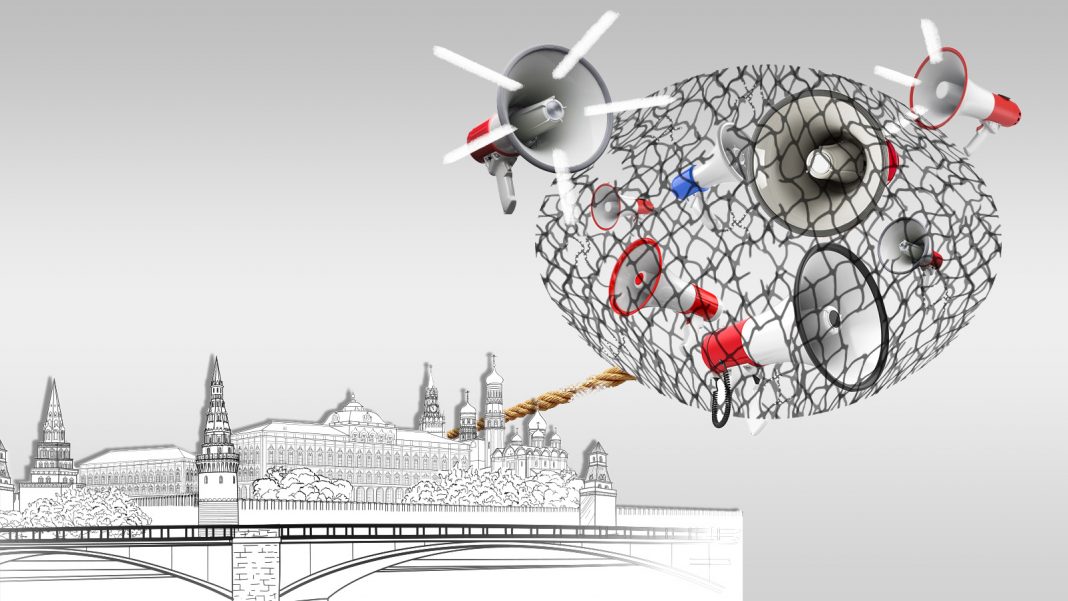

Russian citizens are finding it increasingly difficult to access factual news. Not least because of the law “on responsibility for fakes about the Russian forces” adopted by the Russian parliament on 4 March. The unprecedented crackdown on freedom of speech, closing down several of the last remaining independent media outlets and self-censorship of others, blocking major social media platforms and opening criminal proceedings against Meta (Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp) to declare it an “Extremist Organisation” are some of its direct consequences.

The personal freedom of Russians to voice opinions that are not in line with the official version of events has also been shrinking. Russian police are reportedly arresting people holding blank sheets of paper, policing private cell phones or even detaining a rebellious bicycle. Nevertheless, since the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, netizens, hacktivists and concerned citizens from all over the world have creatively bypassed Russia’s robust propaganda and censorship machine in a constant game of cat and mouse.

News go dark (web)

With independent newsrooms relocating outside of Russia, outlets are encouraging readers to access their publications via alternative routes. Many outlets share information about using a VPN to bypass the censors’ grip. The popularity of VPN services in Russia has exploded, growing more than 1,000 per cent in the past month. Others have gone as far to set up set up dark web versions of their websites and are calling for people to download the Tor browser that is required to access these types of sites. Also, some outlets promote their e-mail newsletters as a way to bypass censorship. In addition, the BBC said it was bringing back shortwave radio transmission to Ukraine and parts of Russia so people can listen to its programmes with basic equipment.

International media organisations based outside of Russia joined forces to create and actively promote their Russian-language content. This includes video news produced by the Finnish broadcasting company Novosti Yle and the French Radio France Internationale. New York Times content in Russian is also available on the dark web.

Media remaining in Russia operate under extreme pressure. Out of solidarity with Novaya Gazeta, which decided to stop reporting on Russia’s war against Ukraine, the Danish daily newspaper Politiken published an uncensored version of the report on Mykolaïv, the besieged Ukrainian city whose residents refuse to surrender to Russian forces despite continuous shelling. The author of the article is a Russian independent journalist, Elena Kostyuchenko, and the report was commissioned by Novaya Gazeta. Politiken, together with the Swedish Dagens Nyheter and Finnish Helsingin Sanomat, now jointly publish Russian translations of their reporting on the Russian war in Ukraine.

We, the people of the world

Communities around the world rushed to tell the story of Ukraine and circumvent the Kremlin’s censorship. Many have resorted to the review function of Google Maps and Tripadvisor to sneak in the truth about the war, but this option is being throttled by the companies. Other resourceful netizens have used their Tinder profiles to spread information about Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Hacktivists have been very active as well. Since the beginning of the war, the infamous group Anonymous has hacked into the Russian streaming services Wink and Ivi, CCTV cameras, and live TV channels Russia 24, Channel One, and Moscow 24 to broadcast war footage from Ukraine.

Most recently, the collective launched a website called 1920.in to help people outside of Russia connect with people in Russian via SMS, WhatsApp and email. The website allows sending messages about the war in Ukraine to randomly selected people in Russia. As of 17 March, more than 30 million messages with the headline “We, the people of the world” have reached people in Russia. The website has been targeted by hacker attacks, but an alternative service – pravdamail – was recently set up by the Estonian tech community.

Guerrilla marketing

These efforts are complemented by professional PR companies that have joined forces to bypass the information wall. They are using ads on popular services such as Yandex to sneak real news about Ukraine into Russia. One of the people behind the movement revealed in an interview with Al Jazeera that his team managed to find several loopholes in the system, allowing to show millions of ads every day. His ads have been reportedly shown 27 billion times and they have been clicked on more than 64,000 times in the past few weeks.

A campaign called Dad Believe has a more personal take on passing on information. The creators of the campaign encourage Russians living abroad to call their family back in Russia and discuss the war. An explainer on how to talk to family members who have been brainwashed for years published on the campaign website may come in handy to remain calm and factual.

For those who do not have relatives in Russia but do speak Russian and want to help set the record straight, there’s another campaign called #CallRussia. Experts behind the campaign have compiled lists of phone numbers, set up a digital phone network and coded a platform, which assigns these numbers to volunteer callers from all over the world. The campaign aims to reach 40 million Russian citizens.

Russia today

Reports from Russia on the attitudes of Russian people towards the war are ambiguous. On the one hand, we see supposed public support for the war and the pro-war Z-sign making rounds in all shapes and sizes. On the other, thousands of people have been detained across Russia for speaking their mind and protesting against the Kremlin’s war, while the draconian new censorship measures deter many from expressing their opposition to the war. Whatever the truth, one thing is certain – the Kremlin is knowingly confusing all of us and steering us away from the simple fact that Russia has launched a large-scale war against Ukraine.