By EEAS, EUvsDisinfo

Click to see full PDF document

The 3rd EEAS Report on Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference (FIMI) Threats maps out the digital infrastructure deployed by foreign actors, mainly by Russia, but also by China, to manipulate and interfere in the information space of the EU and partner countries.

The European External Action Service (EEAS) has released its third report on foreign information manipulation and interference (FIMI) threats. Read the full report here.

Like previous reports, the latest iteration of the report is based on carefully collected data of observed FIMI activity, to identify and analyse the key trends in 2024. Building on the guidance provided by last year’s report on moving toward collective response, the 3rd report on FIMI threats introduces a novel element to analyse foreign information manipulation and interference – the FIMI Exposure Matrix, which was applied to analyse a sample of 505 FIMI incidents involving some 38 000 channels engaged in information manipulation.

EU High Representative of Foreign Affairs and Security Policy/ Vice-President of the European Commission Kaja Kallas presented the report and stated clearly that the threat of FIMI is global and must not be underestimated, because ‘the aim [of FIMI] is to destabilise our societies, damage our democracies, drive wedges between us and our partners and undermine the EU’s global standing.’

Russia and China continue to adapt their FIMI operations

Like previous years, Russia and China remain among the most prolific FIMI threat actors, their tactics, techniques and procedures (TTPs) characterised by continuous adaptation both to harness new and emerging technologies and to circumvent the restrictive measures imposed against them. In this context the use of artificial intelligence has become more frequent in 2024, both to enable and facilitate content creation, including for large Russian state-run FIMI actors like RIA Novosti, and to enable automatisation and the scaling-up of content distribution.

For the Kremlin, FIMI, or the weaponisation of information, is a tool to advance Russia’s geopolitical objectives and, in 2024, can be characterised as an attempt to build a False Façade to hide pro-Kremlin information laundering operations. Russia sought to exploit specific local vulnerabilities with carefully tailored and targeted content, especially zeroing in on elections around the globe. However, undermining Ukraine and Western support to it remained at the forefront of Russia’s FIMI operations in 2024, as it has for the three years of Russia’s full-scale war in Ukraine.

China continued to expand its state-controlled media footprint globally as it deployed multiple FIMI tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs), from classic information manipulation operations to supressing critical voices. Notably, China’s FIMI proxies extend beyond the state-run media enterprise, co-opting private PR companies and influencers to broaden geographic and linguistic coverage, often with the aim of concealing origin and affiliation.

In 2024, China’s FIMI activities continued to operate alongside other threat actors, including Russia, but the cross pollination between Russian and Chinese FIMI ecosystems seems to remain largely opportunistic. However, in terms of narratives, there was a significant convergence on messaging blaming NATO for escalating conflict with Russia.

Elections in the crosshairs

Based on the sampled 505 FIMI incidents, it is evident that FIMI is a global threat with significant local implications, particularly in the context of elections, both within the EU and globally. For example, Russian FIMI actors systematically targeted the European elections in 2024, escalating activity in the weeks leading up the elections and continuing well beyond them.

Outside the EU, Moldova was heavily targeted by Russian FIMI activity. The October–November 2024 presidential elections and the EU membership referendum in Moldova revealed a significant escalation in Russia’s FIMI operations. Russia used a complex, multi-layered, and adaptive FIMI infrastructure. These operations strategically combined existing infrastructure with newly developed assets and campaigns to influence and manipulate voter behaviour. Notably, Russian FIMI infrastructure previously used against Ukraine was redeployed to attack Moldova, adapting networks and narratives to a new front of interference.

Of course, pro-Kremlin attempts to meddle in elections go beyond the incidents sampled in the report. As we have observed and exposed on the EUvsDisinfo database, elections in France and Germany were also frequently in the Kremlin’s crosshairs.

Echoes of Russian FIMI influence in Africa

Russia’s FIMI infrastructure in Africa in 2024 reflects a long-term, multi-layered strategy developed over recent years. In Africa, the Kremlin has also capitalised on regional political shifts, aiming to position itself as a counterpower to the West. As shown in the report, Russia has grown its state-controlled media presence, e.g. by expanding the RT and Sputnik networks, but has also adapted and grown its covert influence networks, such as the African Initiative.

The tip of the FIMI iceberg

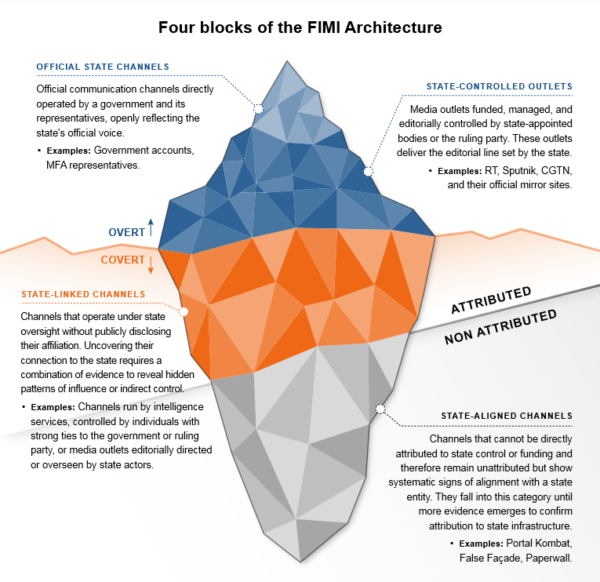

So, how do we know what we know? Because the EEAS has deployed the proposed FIMI Exposure Matrix to uncover the iceberg that epitomises the FIMI architecture. The iceberg analogy is not accidental because much like an iceberg, FIMI architecture can have a more visible part and an often larger, hidden part. Threat actors like Russia and China deploy covert infrastructure to enable their FIMI operations by creating hidden networks that infiltrate local audiences and deliver deceptive narratives. The covert character of these manipulative efforts indicates that FIMI is a hybrid activity.

The FIMI Exposure Matrix is composed of four categories. Three can attributed to a threat actor: 1) official state channels; 2) state-controlled outlets; and 3) state-linked channels. The fourth category cannot be necessarily attributed to a state actor, but these entities still play a significant role in FIMI activities as they show a systematic alignment and similar behaviour characteristics.

Each of these four categories are characterised by specific behavioural and technical indicators. Understanding the modus operandi of each category is crucial to defining and exposing them as FIMI entities. Technical indicators may include public affiliation (and even self-attribution), as well as financial records revealing the sources of funding, and evidence of shared IT infrastructure. Behavioural evidence may include amplification patterns (e.g. mirroring content, automated translations, republishing), as well as using inauthentic AI generated accounts, coordinated messaging and branding similarities. Based on this approach, it is possible to infer a more comprehensive understanding of the role and function various entities play in the overall FIMI architecture.

The EEAS has been building a comprehensive approach to mitigate the threat of information manipulation. The first report on FIMI threats, published in 2023, focussed on how to analyse information manipulation and introduced the FIMI methodology, a groundbreaking step to standardise the approach to FIMI investigations. The next iteration of the report used the methodology to propose a collective response framework to FIMI threats. Now, the third report takes a step further by detailing a practical approach to exposure and attribution – a much needed step to safeguard our democracies in increasingly tumultuous times. Read the report, learn more, and don’t be deceived.

Click to see full PDF document

By EEAS, EUvsDisinfo