2014 marked the end of the post-Cold War era as we knew it and revived the significance of geopolitics. The turmoil in Ukraine has come as the final blow to any hopes of having common, if tough, partner relations with the current regime of the Russian Federation. While the ravages of war and escalating diplomatic tensions have dominated the headlines for many months, the contours of a parallel struggle are becoming impossible to overlook. The formidable information war conducted by the Kremlin erodes Western societies by preying on their internal divisions. The Czech Republic, a former Soviet satellite, is no exception.

A voice in the wilderness

To get an idea of the scale of Russian activities in the Czech Republic one should peruse the relevant parts of the annual reports by the Czech Security Information Service (BIS), which is the leading Czech national intelligence agency. The most recent report for 2013 reveals that already in the year preceding the toppling of president Yanukovych and the ensuing propaganda storm, the actions of Russian intelligence services – along with the Chinese – were priority tasks for BIS in the field of counterintelligence. The document mentions “an extremely high” number of Russian intelligence officers operating undercover as diplomats in addition to spies travelling to the Czech Republic as tourists, academic employees or entrepreneurs.

Russia’s goals are described, in general terms, as taking advantage of influence in the sphere of politics, media as well as the public domain in order to further the economic interests of the Russian Federation. As for the methods, BIS highlights what the former KGB general Oleg Kalugin describes as the heart and soul of Soviet intelligence, i.e. active measures. These include, among others, propaganda and disinformation apart from more sinister ones such as assassinations, which is not mentioned in the document. Active measures require active collaboration from citizens of the Czech Republic, and when building their influential network the Russians are particularly interested in journalists, members of political parties, state officials, lobbyists and activists. To be sure, not every pawn in this game is a willful stooge for Russian interests. Some fall prey to their own naivety.

The 2013 report deplores the inattention on the part of Czech officials and security experts to the security risks posed by this onslaught of Russian espionage. The 9th Security Conference in Prague offers an illustrative example. The event was dominated by the uproar caused by the NSA-surveillance scandal while the danger from the East was not an issue. BIS also explicitly warns of the security implications that the Chinese telecom companies such as Huawei bring with them. However, in the eyes of Czech ministerial officials, this does not discredit Huawei and does not constitute a reason for the company to be excluded from any tender.

By and large, it is not unfair to say that the valuable advice from the central intelligence agency seems to have fallen on deaf ears among the majority of the Czech policymakers and the same goes for other alarming signals.

A tacit acknowledgement

“Russia not guilty of the Katyn massacre”; “Strelkov responds to Khodorkovsky”; “The Ukrainian security services are behind the genocide of Ruthenians”; “Russians do not want AGRIC pests from Poland. Will Polish products end up in the Czech Republic?”; “Putin: We will not get dragged into intrigues and conflicts”. These are some of the headlines one can read on the homepage of The Institute of Slavonic Strategic Studies. These examples are both representative and indicative of the contents of this grossly pro-Russian—or should we say pro-Kremlin?—Internet site. As stated in the records of the Ministry of Justice, the obscure institute behind the site is a civic association registered at the beginning of 2014.

It is neither the existence of ISSS nor the ludicrous scribbling on its website that is the problem here. After all, the association was registered as it fulfilled all legal requirements while freedom of expression guarantees everyone’s right to communicate their views (although the evidential lie in the article relating Katyń may be crossing this line). What does raise eyebrows is that shortly after its registration, ISSS organised a conference for the MPs of the Czech parliament. The event took place rather unsurprisingly under the auspices of the communist party KSCM (The Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia) and was devoted to debunking popular myths about Russia.

What is even more depressing is that the Czech state is donating to blatant propaganda activities on its own territory against better its judgment, as is the case with the young pro-Kremlin, Kiev-born businessman, Alexander Barabanov. The Ministry of Culture financially supports a number of cultural initiatives run by representatives of ethnic minorities, and the Russian minority of around 32,000 is no exception. Among the subsidised cultural activities is a Russian youth association, along with a magazine called Artek published by the above-mentioned Prague-based businessman. Some excerpts from Artek can be described as a fully-fledged Kremlin propaganda tube portraying Putin as the leading peace-maker. This is consistent with the views represented by Barabanov, who received some unearned publicity when he repeatedly labelled the new Ukrainian authorities as fascists on a popular Czech TV show. Despite his Ukrainian background, he does not conceal his intense dislike for western Ukraine. To him, Putin means stability while Belarus is a shining example that needs to be followed. For all his disdain towards the western countries, he sticks to the pragmatic Roman principle pecunia non olet (“Money does not stink.” In other words, the value of money is not tainted by its origins – editor’s note.) and lets the Czech state co-finance his dubious enterprise.

When questioned about the presence and scale of Russian propaganda, politicians from left to right are quite unanimous. This includes the present Minister of Defence, the previous Minister of Foreign Affairs and the present chairman of the parliamentary committee on security. It is when they are asked about possible counter-measures that they lose their tongue. In other words, the acknowledgement of the situation, both widely shared and tacit, does not seem to translate into any comprehensive government-wide strategy. It does not spark off a national debate either apart from a handful of newspaper articles. This should hardly come as a surprise given the pro-Kremlin undercurrents in the society as well as the present foreign policy promoted by the highest echelons of power in the Czech Republic – the Prime Minister and the President.

Strange signals from above

For all the differences between them, there are a couple of traits that the current president, Miloš Zeman, and his predecessor, Václav Klaus, have in common. Both gentlemen possess an unusually high self-esteem and show a startling degree of sympathy for the present Russian policy. After making a few surprisingly hawkish remarks in the initial phase of the Ukrainian turmoil, Zeman has consistently downplayed the significance of the crisis by, among other things, calling it a petty temporal problem – just a mild flu really – compared with the threat posed by the Islamic State, which in his eyes is more like a cancer. He has also been wrapped up in playing semantic games in the public discourse, as if re-branding the aggressive actions against Ukraine from “invasion” to “incursion” or from “war” to “civil war” would have any effect on the reality on the ground. However, such stunts on the part of the Czech president do have one real, albeit probably unintended, impact — a growing confusion among the country’s Western allies.

Zeman has also gained attention abroad thanks to his repeated questioning of the presence of Russian military units in Ukraine in defiance of the evidence gathered by the intelligence agencies of NATO countries as well as foreign and local media correspondents. Expressing such doubts at the NATO summit in Wales was a particularly clumsy thing to do as well as a disservice to Czech foreign policy. It led to caustic remarks from the then Foreign Minister of Sweden, Carl Bildt who suggested that president Zeman came in touch with the Czech national agencies and asked – feigning uncertainty – “There are some Czech intelligence agencies, are there not?”

The proverbial icing on the cake was Zeman’s participation and his speech held at a conference organised by World Public Forum, a NGO presided by Vladimir Yakunin. While not a crime itself, it does send a jarring signal when the president of a EU member country not so much questions as openly rejects the common European policy vis-à-vis Russia and does so during an event arranged by Putin’s close associate and a man who himself is on the sanction list.

It is easier to report about the weird foreign political manoeuvres of the Czech head of state than to account for them. So what can be the motivation behind all of this? One possibility is that these are sincerely held beliefs. It begs the question of whether the president is ill-informed to the point of being delusional or worse still, cynical. Even more importantly, it raises the issue of the role of the people surrounding Zeman in terms of informing his statements and actions. Although we do not have a profound and systematic knowledge about the discussions within the inner presidential circle, we do know the profiles of some of the people Zeman consults. We know that among his occasional external advisers is Ivan David, a former health minister and left-wing PM known for his vehemently anti-American and anti-NATO attitude. David is the leading editor of a conspiracy-mongering alternative news site churning out articles often consistent with the Kremlin line Nova Republika (New Republic). Another interesting and far more important figure is somewhat shadowy businessman Martin Nejedlý, who describes himself as Zeman’s close friend and an advisor in the energy sector. Nejedly is said to have started his business career as a car dealer in Russia and went on to co-operate with Lukoil. Nowadays he is in charge of LUKOIL Aviation Czech, a part of Lukoil Oil Company. He’s present at top meetings and was a member of the presidential team during a recent visit to China. He also accompanied the president on Rhodes.

Another explanation—and we are not talking about mutually exclusive scenarios—is that Zeman takes pleasure in stirring up controversies. His vulgar and provocative statements about Pussy Riot and Mikhail Khodorkovsky fall squarely into this category. That said, dismissing his doings as nothing more than the shenanigans of an enfant terrible of the Czech political scene would be a mistake.

Last but not least, the above is part of the bigger picture which is one of a disconnected foreign policy where the prime minister expresses his perplexity at president Zeman’s statements publicly and criticizes them in the media while promising to talk to the president more often in a rather embarrassing admission of how flawed the internal communication between the two statesmen is. After the Czechs elected Zeman in the country’s first direct elections, the presidential powers and duties have not changed and yet the presidential office has been strengthened in two respects. In psychological and symbolic terms the mandate is stronger in that he’s entrusted with the responsibilities of the head of state directly by the people whereas in purely practical terms, he’s independent of the majority of MPs the way his predecessors were. The implications of these two factors are magnified by the somehow defiant personality of the current president.

Consequently, the current foreign policy is determined by two centers (the presidential palace and the government) which seemingly act on their own, and the resulting confusion is difficult to gloss over. The most visible example of it was when the presidential administration openly started to renounce the heritage of the first post-communist president, Václav Havel, with his value-based foreign policy and emphasis on the concept of human rights. Combined with the agenda of strengthening economic ties with China and Russia, that made it more difficult for Prime Minister Sobotka to represent the country vis-á-vis Western partners. His zealous public assurances of the country’s unshaken stance on the human rights issue were probably meant to dispel the bad impression which prevailed before his visit to the USA some months ago. That might have been the reason why president Obama did not find time to meet the Czech Prime Minister.

To call Sobotka and his government victims of the unruly president would be a gross misrepresentation of the political reality as the governmental coalition has its fair share of poor decisions. One of the most spectacular of them was probably the failure to pass something as uncontroversial as a resolution condemning the Russian aggressive actions against Ukraine and calling for close co-operation with the country’s western allies in September 2014.

Regardless of how one evaluates the way the Czech Republic manages its international relations, two things are sure: It’s unsuitable to deal with the current challenges, Russia’s belligerent course and its propaganda activities being two of them. It is also like a microcosm in that it reflects the lack of consent among EU member states. Both characteristics make it a vulnerable player and a thankful target for pro-Kremlin lobbying campaigns.

Apostles of disinformation

Not unlike many other technologies, the Internet is a double-edged sword and is equally suitable for spreading information and disseminating misinformation. With its variety of platforms and channels, the Internet is also supplanting traditional mass media. That is why cyberspace is one of the most prominent and at the same time least transparent battlefields of the 21st century, and the current clash between Russia and the West is no exception.

The rise and the agenda of the Russian channel RT has rightly drawn the attention of many commentators worldwide. What is less conspicuous but equally alarming is a growing gray area of countless news and opinion websites which render the traditional notion of propaganda both outdated and insufficient for describing reality, as is the case with the RT.

While we are talking about a very heterogeneous category of Internet sites, there are a number of key characteristics they share both in terms of their self-identification and topical range that make it natural to consider them as an entity of sorts, if only a vague one. Their authors and editors describe them using such words as: “alternative”, “free”, “independent” as well as “opposed to political correctness and the mainstream”. These general terms take on a very specific meaning in this context and become something in the way of code words allowing one to recognize this genre almost instantaneously.

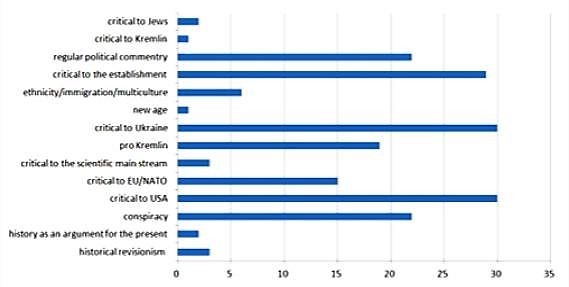

As the ad hoc topical summary below shows, they may not offer a cohesive worldview or ideology but they clearly do have common themes. The comparison is based on a random selection of ten news items from each of the ten reviewed websites. The news items fall into one or more thematic categories that were identified earlier.

Granted, the comparison is lacking in systematic approach and methodology and the semantic fields of some of the categories are included within those of other categories. Still, it gives an idea about the content of these sites. In addition to overlapping interests, the reader encounters recurring claims and in some cases one can observe instances of sharing the same content across this loose network.

Because this article revolves around the Russian information war, the question suggests itself in what sense the above-mentioned media outlets are a part of this war, or, put more explicitly: Do we deal with a direct political affiliation and even possibly Russian financing?

This is a wrong question to ask not only because it requires either access to counter-intelligence information or at least a talented hacker to answer it, but first and foremost because it is not all that relevant for a few reasons.

First and foremost, the traditional notion of propaganda or the fifth column is not adequate here. The content of these sites is better described as information noise. It consists of indisputable facts, commentary, more or less justified social and political criticism mixed with far-fetched claims, speculations, conspiracy-mongering, lies, defamation and propaganda.

For instance, no one denies the existence of Neo-Nazi groups in Ukraine, but when these repeatedly make headlines the prevailing image is that the country is held hostage by extremists who in reality are on the margins of political life as is the case with their counterparts in other countries, including the frightening Neo-Nazi underground in Russia and Germany. Unlike more straightforward propaganda messages, this information noise strategy induces a state of doubt in the reader and a sense of mistrust towards the establishment but does not always give clear-cut answers and does not allow for constructive alternatives. Secondly, this question focuses on the trivial issue of formal affiliation, whereas it is the total effect that should be our concern. The angry counter-culture does not need a mighty political patron. In its hostility towards the establishment, its proponents will happily replicate and disseminate messages shedding a negative light on it no matter where these originate. The pro-Kremlin views presented among many Czechs are partly just a function of their displeasure at their own everyday life and their anger at the powers and organisations they hold accountable for the present state of affairs. The columns, posts and articles may not be commissioned by anyone but the total effect on the readership is equally erosive. The KGB-inspired campaign promoting the disinformation that the USA was behind the HIV virus and the homegrown X-files-style conspiracies foster sentiments of the same kind. Thirdly, while one cannot exclude that one or more of these digital media fall into the category of active measures or is somehow inspired by the Russian side, the rise of a whole range of independent local media outlets with no formal ties to one another or any foreign centres of power is an even more complex issue to combat. They are decentralised, operate legally and take advantage of the freedom of expression and feed into the discontent and the irrational strains present in Czech society, making it susceptible to genuine propaganda.

To sum up, the Czech Republic is too small a country to have its own division of RT or even a version of the RT homepage in its own language. Together with the widespread conviction that the country is somehow on the periphery of world events, this engenders a misguided sense of calm and complacency. The message not so dissimilar from that of RT – and often times much more outlandish and extreme – is circulating on Czech Internet websites and seems to resonate with certain groups of local media consumers. The long-term effect of this barrage of misinformation on the public is impossible to determine, but it does not make one feel optimistic. Ill-informed citizens make ill-informed decision-makers, not least in their capacity as voters.

Sławomir Budziak is a Polish columnist and translator based in the Czech Republic. He has published a number of articles on politics and society in Eastern Europe for Polish, Norwegian and British media.

Source: New Eastern Europe

Written by Sławomir Budziak